- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fiscal Monitor, October 2016 : Debt: Use It Wisely

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fiscal Monitor, October 2016 : Debt: Use It Wisely by Marialuz Moreno Badia in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

2016eBook ISBN

9781513560601Chapter 1. Debt: Use It Wisely

Introduction

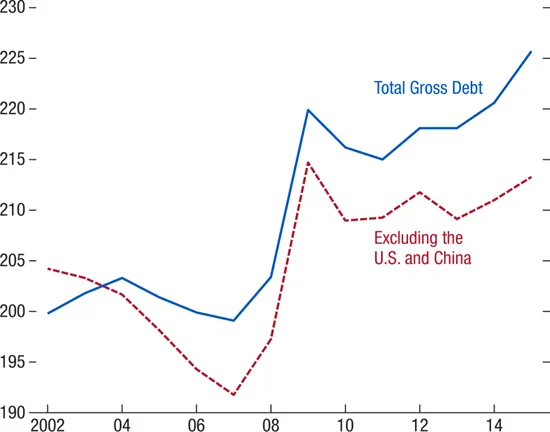

The global gross debt of the nonfinancial sector has more than doubled in nominal terms since the turn of the century, reaching $152 trillion in 2015.1 About two-thirds of this debt consists of liabilities of the private sector. Although there is no consensus about how much is too much, current debt levels, at 225 percent of world GDP (Figure 1.1), are at an all-time high. The negative implications of excessive private debt (or what is often termed a “debt overhang”) for growth and financial stability are well documented in the literature, underscoring the need for private sector deleveraging in some countries. The current low-nominal-growth environment, however, is making the adjustment very difficult, setting the stage for a vicious feedback loop in which lower growth hampers deleveraging and the debt overhang exacerbates the slowdown (Buttiglione and others 2014; McKinsey Global Institute 2015; Gaspar, Obstfeld, and Sahay 2016). The dynamics at play resemble that of a debt deflation episode in which falling prices increase the real burden of debt, leading to further deflation. Weak bank balance sheets in some countries have further contributed to dampening economic activity, as private credit has been curtailed beyond what would be desirable.

Figure 1.1. Global Gross Debt

(Percent of GDP; weighted average)

Sources: Abbas and others 2010; Bank for International Settlements; Dealogic; IMF, International Financial Statistics; IMF, Standardized Reporting Forms; IMF, World Economic Outlook; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; and IMF staff estimates.

Note: U.S. = United States.

A key priority in those countries currently facing a private debt overhang is to identify policies that can help with the repair process while minimizing the drag on the economy. This task is particularly challenging because the room for policy maneuver has narrowed since the start of the global financial crisis and the effectiveness of some policies (notably monetary) may be more limited. These constraints put a premium on how to use the fiscal space that may still be available, including leveraging complementarities across different policy tools to get more mileage out of any fiscal intervention. Against this backdrop, this issue of the Fiscal Monitor addresses the following questions:

- How high is global private and public debt, and how far are we in the deleveraging process?

- Can fiscal policy help with private sector deleveraging and, if so, how?

This issue of the Fiscal Monitor goes beyond the existing literature, significantly expanding the country coverage of previous studies by including emerging market economies and low-income countries as well as advanced economies. It also looks at the sectoral composition of leverage by analyzing both public and private nonfinancial debt (for households and nonfinancial corporations). The analysis attempts to cover the asset side as well to arrive at broader measures of the health of private and public balance sheets. A key contribution is the use of a novel analytical framework developed by Batini, Melina, and Villa (2016), which explicitly models the interactions between private and public debt in analyzing the role of fiscal policy during the deleveraging process.

The chapter starts by giving an overview of debt trends around the world and taking stock of the deleveraging process. Next, it explains why debt levels matter for growth as well as macroeconomic and financial stability. It then examines empirically and through model simulations how fiscal policy can help a country get out of a debt overhang while drawing on country case studies to illustrate the types of measures—and key design features to enhance their effectiveness—that would support a smooth deleveraging process.

The main findings can be summarized as follows:

- Private debt is high not only among advanced economies, but also in a few systemically important emerging market economies. High private debt not only increases the likelihood of a financial crisis but can also hamper growth even in its absence, as highly indebted borrowers eventually decrease their consumption and investment.

- The chapter’s analysis also suggests that the current process of private sector deleveraging in highly indebted countries will likely take some time to play out. General government balance sheets have also weakened, particularly in advanced economies, although low interest rates have temporarily eased budget constraints.

- Empirical analysis shows that fiscal policy can significantly reduce the depth and duration of a financial recession associated with a private sector debt overhang. However, a government’s ability to play such a stabilizing role depends on the health of its fiscal position prior to the crisis, especially in emerging market economies. This underscores the importance of building fiscal buffers and properly accounting for financial cycles in assessing the strength of the fiscal position in periods of expansion while ensuring the close monitoring of private debt to limit fiscal risks (IMF 2016a).

- At the current juncture, the array of growth-friendly fiscal policies should include measures that facilitate the repair of balance sheets in those countries facing a private debt overhang or where the financial system is impaired. This is particularly important in some European countries, where the weak banking system is retarding the recovery, and in China, where high corporate debt levels raise the risk of a disorderly deleveraging. Such targeted fiscal interventions may include government-sponsored programs to help restructure private debt—such as subsidies for creditors to lengthen maturities, guarantees, direct lending, and asset management companies—that can facilitate the deleveraging process. To the extent that weaknesses in a country’s financial system threaten financial stability, impair the credit channel, and hamper growth, addressing the underlying problems swiftly is essential.

- The design of such fiscal interventions is critical for minimizing their cost, mitigating moral hazard, and ultimately ensuring their success. The limited policy room calls for exploiting the synergies among fiscal, monetary, and financial, as well as structural, policies to facilitate the deleveraging process, reinvigorate growth, and bring inflation to target.

How High Is Debt?

This section provides a broad perspective on global debt, expanding the country coverage of previous studies and looking at recent developments in advanced economies, emerging market economies, and low-income countries. It also explores the drivers behind recent trends and how far we are in the deleveraging process.

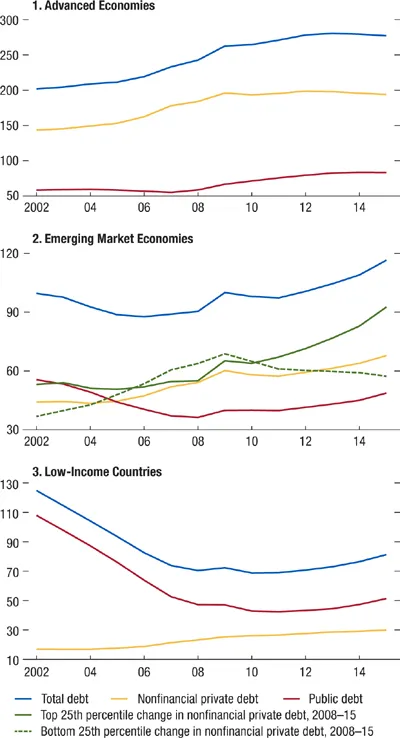

The Global Picture

The genesis of the global debt overhang problem resides squarely within advanced economies’ private sector.2 Enabled by the globalization of banking and a period of easy access to credit, nonfinancial private debt increased by 35 percent of GDP in advanced economies in the six years leading up to the global financial crisis (Figure 1.2). The credit boom was not limited to the U.S. mortgage sector but was broad based within this country group, with more than half of the debt coming from households (Figure 1.3). In emerging market economies, the increase in nonfinancial private debt during this period was also driven by the household sector but was generally less pronounced. Low-income countries, on the other hand, were largely shielded, as many were (and still are) in the process of financial deepening (IMF 2015a). Interestingly, public debt declined across all country groups up to 2007, particularly among low-income countries—mainly as a result of debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiatives. Nevertheless, there is evidence that the financial cycle may have overstated the strength of government balance sheets in some advanced economies that experienced a real estate boom (Budina and others 2015).

Figure 1.2. Gross Debt by Country Groups

(Percent of GDP, simple average)

Sources: Abbas and others 2010; Bank for In...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Assumptions and Conventions

- Preface

- Executive Summary

- Chapter 1. Debt: Use It Wisely

- Country Abbreviations

- Glossary

- Methodological and Statistical Appendix

- Fiscal Monitor, Selected Topics

- IMF Executive Board Discussion Summary

- Figures

- Footnotes