- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Value Added Tax : International Practice and Problems

About this book

NONE

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

1988eBook ISBN

9781557750129PART I Structure of VAT

CHAPTER 1 Why a Value-Added Tax?

The latest innovation is the value-added tax. Its emergence in France illustrates the process by which a sort of continuing ferment of improvisation now and then gives rise to an invention of the first order.

—CARL S. SHOUP, “Taxation in France,” National Tax Journal, Vol. 8, December 1955, p. 328

The rise of the value-added tax (VAT) is an unparalleled tax phenomenon. The history of taxation reveals no other tax that has swept the world in some thirty years, from theory to practice, and has carried along with it academics who were once dismissive and countries that once rejected it. It is no longer a tax associated solely with the European Community (EC). Every continent now uses the VAT, and each year sees new countries introducing it. Various similes come to mind; VAT may be thought of as the Mata Hari of the tax world—many are tempted, many succumb, some tremble on the brink, while others leave only to return, eventually the attraction appears irresistible. This book has a modest intent. It tries to illustrate how different countries have tackled the problems of VAT that are common to most. It debates the major issues and discusses preferred solutions. The book is divided into three main sections: the practice and problems of VAT in terms of VAT’s structure (Part I), effects (Part II), and administration, including taxpayer compliance (Part III).

In this opening chapter there are three main parts. First, a brief account of the different ways a tax can be levied on value added. Second, an examination of the reasons why countries decide to switch to a VAT. Finally, a most important consideration, why some countries have decided (for the time being?) not to adopt a VAT.

VAT in Theory

Four Basic Forms1

Value added is the value that a producer (whether a manufacturer, distributor, advertising agent, hairdresser, farmer, race horse trainer, or circus owner) adds to his raw materials or purchases (other than labor) before selling the new or improved product or service. That is, the inputs (the raw materials, transport, rent, advertising, and so on) are bought, people are paid wages to work on these inputs and, when the final good or service is sold, some profit is left. So value added can be looked at from the additive side (wages plus profits) or from the subtractive side (output minus inputs).

If we wish to levy a tax rate (t) on this value added, there are four basic forms that can produce an identical result:

- (1) t (wages + profits): the additive-direct or accounts method;

- (2) t (wages) + t (profits): the additive-indirect method, so called because value added itself is not calculated but only the tax liability on the components of value added;

- (3) t (output – input): the subtractive-direct (also an accounts) method, sometimes called the business transfer tax; and

- (4) t (output) – t (input): the subtractive-indirect (the invoice or credit) method and the original EC model.

Direct Versus Indirect Methods

Given that there are four possible ways of levying a VAT, why has only one (method 4, above) been popular? Most taxes are levied by first calculating the tax base (income, sales, wealth, property values, and so on) and then applying a tax rate to that value. The same method might be thought sensible for a VAT. The value added should be calculated directly (methods 1 or 3, above) and the tax rate applied. In practice, the method used (number 4) never actually calculates the value added; instead, the tax rate is applied to a component of value added (output and inputs) and the resultant tax liabilities are subtracted to get the final net tax payable. This is sometimes called the “indirect” way to assess the tax on value added.

Why should an indirect method of tax calculation be used for VAT when the alternative seems so much more straightforward? There are four principal reasons. The most important consideration is that the invoice method (number 4) attaches the tax liability to the transaction, making it legally and technically far superior to other forms. As will be explained in later chapters, the invoice becomes the crucial evidence for the transaction and for the tax liability.

Second, as discussed in Chapter 13, the invoice method creates a good audit trail. Experience in countries such as Benin and Mauritania that use method 3—what in French is called the base sur base method—suggests that without the invoice for each transaction problems emerge, first, in ensuring that inputs are deducted only when tax is paid and, second, when inputs exceed taxable sales. This same method has been described, in Canada, as not leaving a good audit trail and as practically eroding the revenue base despite “the Calvinistic nature of the Canadian populace.”2

Third, to use methods 1 and 2, which are accounts based, profits need to be identified. As company accounts do not usually divide sales by different product categories coinciding with different sales tax rates, and as they certainly never divide inputs by differential tax liabilities, it is clear at once that the only VAT that could be levied on an additive basis would be a single rate VAT. If a multiple rate VAT is wanted, it rules out using methods 1 and 2.

Finally, the easiest way to calculate a VAT, using the subtractive method, appears to be the calculation of the value added (output minus input) and then to apply the tax rate to that figure (method 3). In practice, companies do not find it convenient to calculate their value added in this way month by month, as purchases, sales, and inventories can fluctuate greatly. Firms may have to carry stocks that change, according to the type of production, the seasonality of trade, or anticipated interruptions of supplies. Again, this procedure is only practical using a single rate. In fact, calculating the direct value added is easiest through the trader’s annual accounts, and so this method of deriving a VAT (in addition to methods 1 and 2) is also an “accounts method.”

Thus, to date, method 4, the invoice or credit method, is the only practical one. The tax liability can be calculated week by week, monthly, quarterly, or annually. It is the method that allows the most up-to-date assessments and also allows more than a single rate to be used.

Capital Purchases

This brings us to another problem skated over in the initial presentation. How do we treat substantial purchases of long-lasting inputs (that is, capital goods)? According to the methods already mentioned, capital purchases would be inputs and would be deducted from any sales. This, of course, can cause huge fluctuations in tax liability as the purchase of, say, a new factory could occur in one month, and lead to negative value added in many of the succeeding months. Alternatively, using the additive method, profits are usually calculated after allowing for only a portion of the cost of a capital purchase (depreciation). Rarely do income tax authorities allow traders to expense their capital inputs (that is, treat each purchase as an immediate expense so that buying a factory becomes the same as buying an automobile or buying a meal); instead, elaborate rules are designed to allow different assets to be depreciated over different lengths of time (for example, machines over 7 years and buildings over 20 years). To make a VAT calculated under the full consumption base of the subtraction method (where all capital purchases are offset at once against sales) exactly the same as a VAT on the additive base, a different calculation of profits would have to be adopted. Depreciation would be abolished and all capital purchases would be offset at once in the accounts, thus making profits much smaller in the early years of capital purchases and much larger in later years, when the usual depreciation would not be deducted. Clearly, the profits shown for income tax purposes in the “profit and loss accounts” would differ hugely from those calculated for VAT.

This is not to say that one way is right and the other wrong—just that they produce very different results.

To the Retail Sale?

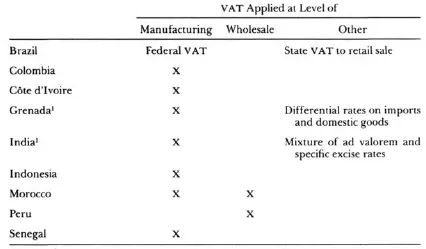

Although VAT is usually thought of as applied to all stages of production including the retail sale, this is not necessarily the case. Table 1-1 shows nine countries that do not apply the VAT at the retail stage (though two, Grenada and India, are not really using a VAT although the name is implied in their legislation). Two countries (Morocco and Peru) apply the VAT through the wholesale stage and the others only to the manufacturing level. It should be mentioned that some countries (for example, Kenya) employ a manufacturers sales tax that allows credit for tax paid on inputs and is, therefore, practically a single-stage VAT.

Table 1-1. Countries That Do Not Apply a VAT Through the Retail Sale

Source: See text.

1 Not really a VAT; see section on “Tax Evolution and Efficiency,” below.

It is clear that all these less-than-complete VATs create problems. All involve a much smaller tax base than one which includes retail sales and, therefore, their tax rates must be higher to yield an equivalent revenue. A VAT to the wholesale level must define a wholesale price because traders often combine manufacturing and wholesale activities as well as wholesale and retailing activities; this leads to a complex set of rules or regulations defining “up-lifts” from factory gate prices or establishing standard discounts on retail prices. A VAT through the wholesale stage should only be considered as a temporary interim arrangement on the way to extending the VAT fully to the retail stage. It is doubtful whether the inefficiencies for both taxpayer and administration ever make it worthwhile other than as a temporary arrangement.

The VAT on manufacturing and importation is more common. It allows a developing economy to levy a buoyant tax on an ad valorem principle and accustom its traders to a credit system. Frequently, the small manufacturers are exempt and, de facto, the VAT is a tax on imports and on large, well-organized industry, especially multinationals. After a few years’ experience, the manufacturing VAT can be extended to the retail level. While this is a more attractive option than the VAT to the wholesale level, it involves an even smaller tax base. However, experience gained from the more limited base and the use of credits allows the VAT to be extended to the sale of all goods and services. (Argentina, Bolivia, and Korea used a manufacturing sales tax with a credit mechanism before moving to a complete VAT.) Of course, there are still problems. In Morocco, where there are some vertically integrated firms, the VAT, although formally levied on manufacturers and wholesalers, can extend right through to the retail stage; a provision allows that an enterprise selling to a connected enterprise (that is, wholesaler to retailer) has to pay VAT on behalf of the retailer. This provision is only included to catch cases of abuse, and, where a genuine internal transfer price can be proved, it is accepted. Nevertheless, this sort of provision exemplifies the difficulties faced by systems that do not apply VAT through the retail stage.

Prices Inclusive or Exclusive of Tax?

The final possible variation in VAT is whether or not the tax rate is levied on a price inclusive or exclusive of the tax liability. A 10 percent VAT, on a price exclusive of VAT, is clear to the consumer. However, it does mean letting the purchaser know both the price before VAT is applied and the amount of tax that must be paid. Alternati...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I: Structure of VAT

- Part II: Effects of VAT

- Part III: VAT Administration and Compliance

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index

- Tables

- Footnotes