eBook - ePub

Financial Liberalization, Money Demand, and Monetary Policy in Asian Countries

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Financial Liberalization, Money Demand, and Monetary Policy in Asian Countries

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Financial Liberalization, Money Demand, and Monetary Policy in Asian Countries by Robert Corker, and Wanda Tseng in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

1991eBook ISBN

9781557752208III. Money Demand and Financial Liberalization

This section investigates the implications of financial liberalization for money demand in the Asian countries, focusing on the stability and predictability of broad and narrow monetary aggregates during the 1980s. The possible effects of financial liberalization on money demand are discussed, followed by the theoretical and empirical issues that arise in estimating money demand functions. Then the empirical results are presented and analyzed and conclusions are drawn together.

Effects of Financial Liberalization on Money Demand

The existence of a stable and predictable relationship between monetary aggregates, economic activity, prices, and interest rates is a crucial element in the formulation of monetary policy. Financial liberalization that improves the quality of economic signals, alters the institutional environment, and expands the array of financial opportunities creates potential for instability in money demand.

For the purpose of analyzing the possible effects on money demand, it is useful to group financial liberalization into three broad categories. First, interest rates that better reflect the economic return and riskiness of financial assets could prompt portfolio shifts. The nature of such onetime shifts in the demand for money would depend on the monetary aggregate in question and on which interest rates were liberalized: if, for example, interest rates on time deposits increased after liberalization, the demand for broad money might rise at any given level of income, but the demand for narrow money might decline.

In principle, the portfolio shifts could be predicted by money demand functions containing appropriate interest rate terms. But, in practice, interest rates might not have varied sufficiently prior to liberalization to allow for measurement of their effects on portfolio choices. As interest rates became more flexible, previously latent roles for interest rates in determining money demand could, therefore, become transparent.

Second, shifts to indirect monetary policy instruments might alter the observed relationship between monetary aggregates, economic activity, prices, and interest rates. In particular, the effective rationing of credit under direct credit controls could be alleviated following a shift to indirect monetary policy instruments making money more demand—as opposed to supply—determined. Because money demand relationships estimated prior to the policy change might not have properly identified money demand behavior, they could prove to be poor predictors of monetary developments after the policy change.

Third, measures to improve the functioning and depth of financial markets could prompt both portfolio shifts and alter the sensitivity of money demand to changes in incomes and interest rates. For example, measures to promote competition among financial institutions could lower transactions costs in financial markets and cause money demand to respond more rapidly to interest rate changes than before. Alternatively, changes in the regulation of financial institutions could prompt a reassessment of the relative risk of different financial assets, leading to both discrete portfolio adjustments and a change in the interest elasticity of money demand.

More generally, measures that promote financial market development could result in the availability of new, attractive assets leading to gradual portfolio shifts away from monetary assets. These shifts might occur independently of developments in income and interest rates. In addition, the returns on the new assets might become important determinants of money demand. Such assets could include foreign assets, if external capital flows were liberalized, as well as domestic assets such as stocks and bonds. However, to the extent that the policy of financial market development encouraged reintermediation, that is, attracted domestic savings away from unofficial “curb” markets, the direction of the effects on broad monetary aggregates would be less clear cut: as the size of curb markets diminished, the demand for all financial assets, including money, might increase.

In summary, financial liberalization could lead to onetime or more gradual shifts in the level of money holdings, as well as to changes in the measured income and interest elasticity of money demand. In some cases, financial liberalization may help to make more transparent the relationship between money and interest rates that may not have been detected previously.

As a practical challenge, it is important to distinguish between the various effects of financial liberalization because they have different implications for understanding the evolution of monetary aggregates. For instance, onetime changes in money holdings might be associated with temporary instability in money demand relationships during the period of liberalization. But changes in the income and interest rate elasticity of money demand, as well as new influences on money demand, might take longer to detect, rendering money demand relationships unstable over a longer period.

As discussed in Section II, virtually all Asian countries undertook financial liberalization during the 1980s, although the pace and scope of reforms varied substantially. For most of the countries, financial liberalization proceeded gradually and on many fronts: it may, therefore, be difficult to detect significant, discrete shifts in money demand. Only in a few countries, notably Indonesia, was liberalization concentrated in one or two major reform initiatives around which more clear-cut breaks in behavior might be expected.

Regardless of differences in financial liberalization, monetary developments during the 1980s in these countries shared some similar features. In particular, the ratio of broad money (defined here as currency plus demand and time deposits in the banking system) to income tended to increase, reflecting rapid growth in quasi-money balances: the share of quasi-money in broad money increased in all countries (Chart 2).8 By contrast, the ratio of narrow money (currency plus demand deposits in the banking system) to income, although generally more volatile than that of broad money to income, did not show a consistent trend across countries: in some countries it exhibited a downward trend, while in others it showed little trend or even tended to rise. However, it is not clear from Chart 2 whether the monetary trends of the 1980s differed significantly from those of the 1970s. And even if such breaks were apparent, it would be important to separate the effects on monetary developments resulting from financial liberalization from those arising from the changed economic environment of the 1980s. To do this, a more formal analytical framework, described below, is required.

Specification and Estimation Issues

Following is an outline of an empirical model that will be used to investigate the stability and predictability of money demand. In this regard, there are a number of interrelated issues concerning the specification and estimation of the model that have a direct bearing on how instability might be detected and analyzed.

Specification Issues

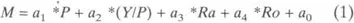

Theories of money demand attempt to explain one or more of the characteristics of money, stressing, in particular, the role of money in fulfilling transactions needs and providing a store of value.9 However, regardless of their theoretical background, a wide variety of models of money demand converge ultimately to a specification in which money depends on a scale variable (income or wealth), prices, and interest rates. This relationship can be written as

where, M is money; P the general price level; Y aggregate incomes; Ra the interest rate on alternative assets: and Ro the return on money.10 Variables other than interest rates are expressed in logarithms. A priori, the coefficients a1, a2 and a4 are expected to be positive, while the coefficient a3 is expected to be negative. For a narrow monetary aggregate, the “own” return would be close to zero and the coefficient a4 probably irrelevant; this would not be the case for a broader monetary aggregate that included a sizable interest-bearing component. In a purely portfolio model of asset demands, the coefficient a3 would be equal in size, but opposite in sign, to the coefficient a4 so that money demand only depended on relative asset returns. The coefficient a1 in most theoretical models would be expected to be close to one: indeed, this condition is usually imposed as, for example, in the earlier study of monetary policy in Asian countries (see Aghevli and others (1979)).

Whereas equation (1) is a fairly general theoretical specification of a money demand function, it assumes that money holdings adjust instantaneously to desired levels following a change in prices, incomes, or interest rates. In practice, this would not be the case for two main reasons. First, the adjustment of financial portfolios is not costless and individuals and corporations will lend to strike a balance between the cost of deviating from desired holdings and the cost of adjusting the level of their actual money holdings. Second, most theoretical models suggest that money demand depends on expected prices, incomes, and interest rates that need not always be related to actual levels of these variables. Allowing for some slow adjustment of expectations in response to new information would again introduce some sluggishness into the adjustment of actual money holdings to desired money holdings. In principle, it would be best to separate out the two sources of adjustment lags, but in practice it is difficult.11

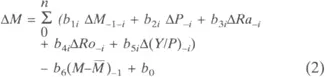

Empirical attempts to capture the sluggish adjustment of money demand toward desired equilibrium holdings have often employed the assumption of partial adjustment in which a fixed proportion of the difference between desired and actual holdings diminishes each period.12 Recently, however, this approach has been criticized as overly restrictive because it assumes that adjustment costs and expectations can be captured in a very specific, simple fashion. In this analysis, an error correction dynamic specification is used. The error correction specification—to be discussed more fully below—can be thought of as a more general, intertemporal version of partial adjustment in which expectations are based on available information (see Nickel (1985)). The error correction money demand function can be written in the form:

where the symbol ∆ represents a first difference of a variable and the subscripts attached to the variables represent lagged v...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- I. Introduction and Summary

- II. Financial Liberalization

- III. Money Demand and Financial Liberalization

- IV. Implementation of Monetary Policy

- V. Concluding Observations

- Appendices

- References

- Tables

- Footnotes