- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tax Policy Handbook

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tax Policy Handbook by INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

1995eBook ISBN

9781557754905General Sales/Turnover Tax

Tax Cascading: Concept and Measurement

HOWELL H. ZEE

• What is tax cascading, why is it undesirable, and what are its major determinants?

• How can tax cascading be illustrated through some simple analytics?

• How can the degree of tax cascading be estimated?

Whenever a commodity or service is taxed more than once under one tax as it passes through various stages of the production-distribution chain, for example, from the manufacturing to the retail stage, tax cascading results. A classic tax that gives rise to cascading is the multi-stage general turnover tax.8 Under this tax, every sales transaction is taxed, possibly at different stage-specific or transaction-specific rates, or both. Thus, a tax of x percent could be imposed on the sales of rubber, and a tax of y percent could be imposed on the sales of tires. Since the value of the rubber is incorporated into the value of tires, the former is taxed twice. It could, in fact, be taxed several more times, as would be the case if, for example, the sales of the tire wholesaler who buys the tires from the manufacturer are also subject to a tax of z percent. It is easy to surmise from the above that the effective tax burden of a cascading tax on a taxed commodity or service, by the time it reaches the final consumer, could be much higher than the tax’s nominal rate that is explicitly applied at the stage where the consumer makes his purchases. To put it differently, even if a commodity or service is exempted from tax at the retail stage, it may well be the case that its price would include tax mixeds stemming from taxes imposed at earlier stages on the various inputs used in its production. The true burden of a cascading tax is, therefore, frequently hidden from the consumer.

A cascading tax is universally regarded as undesirable, since by taxing transactions at stages prior to the stage of final consumption, it leads to more severe economic distortions than would a tax imposed only on final consumption, such as a retail sales tax or a full-fledged value-added tax (VAT) extended to the retail stage.9 Short of replacing a tax that cascades with one that does not, however, there are various mechanisms available to alleviate the extent of the cascading. These mechanisms are discussed in the next section entitled “Mechanisms to Alleviate Cascading.”

Determinants of the Degree of Cascading

The degree to which the true burden of a cascading tax is passed on to the final consumer depends on a number of complex but intertwined factors. Some of the more important ones are identified in this chapter.

Demand and supply elasticities

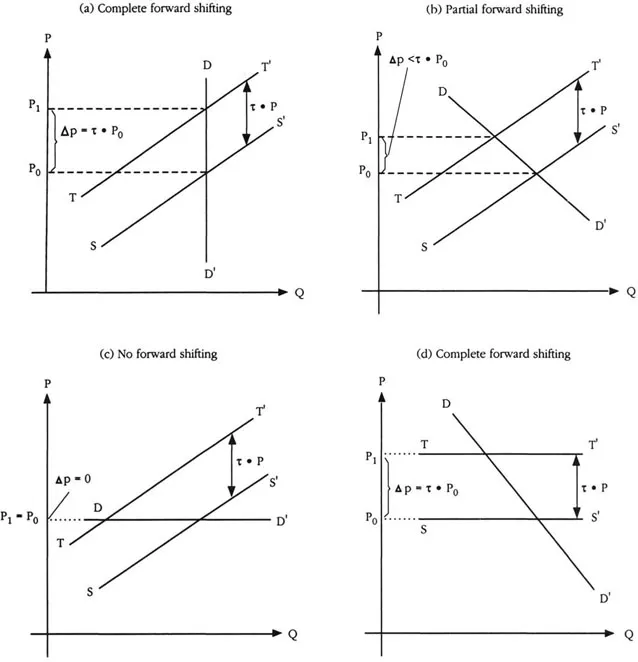

As is well known, the ability of a producer to shift the burden of the tax on his output to the purchaser depends on the relevant demand and supply elasticities. In a partial equilibrium framework of a single taxed commodity, the outcomes of four different combinations of such elasticities are illustrated in the four panels of Figure III.1. In each of the panels, DD’ is the demand curve, SS’ is the pretax supply curve, and TT’ is the posttax supply curve. The vertical distance between the SS’ and TT’ curves at every price level Pis simply equal to x-P, where τ is the ad valorem tax rate. If Po and P1 denote the pretax and posttax equilibrium price levels, respectively, then it is easily seen from Figure III.1 that the extent to which the price level would rise after the imposition of the tax would depend on the particular configuration of the demand and supply curves (the symbol Δ in Figure III.1 is used to denote a change in any variable). Full forward shifting of the tax, in the sense that the purchaser bears the entire tax burden because the price level is increased by the same rate as the tax rate, would occur when either the demand curve is vertical (panel (a) of Figure III.1), that is, the elasticity of demand is zero, or the supply curve is horizontal (panel (d) of Figure III.1), that is, the elasticity of supply is infinite. No forward shifting would result if instead the demand curve is horizontal (panel (c) of Figure III.1). Under most circumstances where neither the demand nor the supply curve displays an extreme elasticity, a partial forward shifting of the tax can be expected (panel (b) of Figure III.1).

Figure III.1. Demand and Supply Elasticities and the Forward Shifting of the Tax Burden

As is evident from Figure III.1, the tax affects either the price or the quantities demanded, or both, of the taxed commodity, which in turn will have repercussions on other (even if nontaxed) commodities. Hence, the ultimate extent to which the tax is shifted forward cannot be determined until a complete general equilibrium analysis is undertaken. Voluminous literature on the (computable) general equilibrium effects of taxation has been developed (see, for example, Shoven and Whalley (1972)). Nevertheless, in most policy analyses of the economic impact of indirect taxes, it is not uncommon to adopt a short-run, partial equilibrium focus, in which case, it is appropriate to assume that the complete forward shifting of an indirect tax, corresponding to panel (d) of Figure III.1, will take place in the first instance.

The ratio of taxed to nontaxed inputs

The magnitude of the tax burden contained in the producer prices at each stage along the production-distribution chain depends on the ratio of taxed to nontaxed inputs at that stage, as well as such ratios at earlier stages. The lower these ratios, the smaller the tax burden. Food prices in many developing countries, for example, normally contain a relatively low tax component, as most agricultural inputs used in food production are tax-exempt.

The degree of price pyramiding

Price pyramiding at any given stage of production or distribution occurs when the seller raises his output price in excess of the tax burden on his inputs (see the following segment). This can occur, for example, if he has some monopolistic power and is, therefore, able to engage in the kind of pricing behavior that would allow him to derive additional profits whenever taxes are increased which are used as a convenient pretext to justify such behavior.

The number of stages in the production-distribution chain

The greater the number of stages of production and distribution a commodity passes through before reaching the final consumer, the greater the number of times taxed inputs would be subject to multiple taxation, and therefore, the higher the degree of the resultant cascading.

It is often difficult in practice to disentangle the complex interactions among the above factors in analyzing the extent of cascading contained in the price of any particular commodity. Nevertheless, some useful simple analytics can be developed for a systematic investigation of the problem.

Simple Analytics of Cascading

Tax burden shifting in a single production-distribution stage

To set the stage for a formal analysis, let p be the producer price of a commodity, k the input cost per unit of output, v the commodity’s per unit value added, τ the ad valorem tax rate on taxable inputs, and γ the fraction of total inputs subject to tax. It then follows that

Define the variable δ as the ratio of value added to input cost inclusive of the tax, that is

Using equation (11), equation (10) can be rewritten as

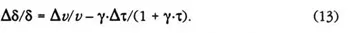

Thus, δ can be interpreted as a markup margin on the input cost inclusive of the tax. If the input cost exclusive of the tax (k) is held constant, then from equation (11), it is clear that any proportional change in the markup margin must stem from an excess of a proportional change in the value added over that in the tax rate, that is,

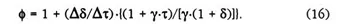

Equation (13) is crucial in describing the pricing behavior of the producer. To see this, first define φ as the elasticity of p with respect to τ:

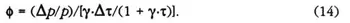

φ measures, of course, the percentage change in p as a result of a 1 percent change in τ (evaluated at the point (1 + γ·τ)). But directly from equation (12), the proportional change in p is simply

Hence, by substituting equation (15) into equation (14),

φ can be restated as

Equation (16) indicates that a critical factor in determining φ is the expression (Δδ/Δτ), which measures the response of the markup margin δ to a change in the tax rate τ. This response is, in turn, dependent on the extent to which the producer is willing to let the value added of his output change, as given by equation (13). Two limiting benchmark cases can be identified.

Case A. Full price pyramiding (Δδ = 0).

If the producer does not allow his markup margin to change, that is, Δδ = 0, then it follows immediately from equation (16) that φ = 1, so that a 1 percent increase in the tax rate leads to a full 1 percent rise in the output price, irrespective of the proportions of taxed to nontaxed inputs and taxed inputs to value added. A producer who engages in this type of pricing behavior would clearly have his value added increased as a result of the tax change. Indeed, it can be seen that, from equation (13), the proportional change in his value added would be equal to the proportional change in the tax rate, when Δδ = 0.

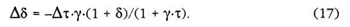

Case B. No shifting of the tax burden (Δυ = −γ·κ·Δτ).

If for some reason the producer is unable to shift the tax burden forward at all,10 then the incidence of any tax change would fall entirely on his value added, that is, Δυ = −γ·κ·Δτ. Substituting this into equation (13) shows that his markup margin is changed according to

It then follows from equation (16) that φ = 0, that is, there is no change in the producer price ρ This result is again independent of γ

The above two cases clearly bracket all possible outcomes on the producer price in response to a change in the tax rate. An interesting intermediate case, for example, would be that the producer merely protects his value added (Δυ = 0) in the face of the tax change. In this case, from equation (13), his markup is changed by Delta;δ = Δτ·δ·γ/(1 + γ·τ). Substituting this into equation (16) yields φ = 1/(1 + δ) < 1. Hence, the proportional change in the producer price is positive but less than the proportional change in the tax rate, and, since the magnitude of δ is inversely related to both κ and γ (see equation (11)), the extent of the price change is larger the higher the ratios of taxed to nontaxed inputs and taxed inputs to value added.

A synthetic rule

Quite frequently, it is useful to conduct simulation exercises to analyze the price impact of replacing one tax with another under different assumed degrees of tax burden shifting. For this purpose, it would be analytically convenient if all the different possible changes in the producer price between, and inclusive of, the above two limiting cases could be captured through varying a single parameter. The simplest procedure to achieve this is to conceptualize the pricing mechanism as if it operates, not according to equation (10), but according to the synthetic rule of

where 1 ≥ α ≥ 0 and A is a nonzero constant. Thus, the full price pyramiding case implies α = 1, and the case of no tax burden shifting implies α = 0. Varying α between zero and unity captures all possible outcomes, including the intermediate case discussed above where the producer’s pricing behavior is such that his value added is not affected by the tax change.

Cascading and multiple stages of production and distribution

With multiple stages of production and distribution, the (possibly different) pricing behavior of producers, tax rate, ratio of taxed to nontaxed inputs, and proportion of taxed inputs to value added at each stage will all have a bearing on the ultimate impact of cascading on the price the consumer faces. The analytics developed above pertaining to a single stage cannot, therefore, be generalized in a simple way to the case of multiple stages. As before, however, an interesting benchmark case can be identified under the special assumption that all producers engage in full price pyramiding behavior.

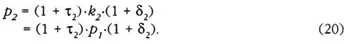

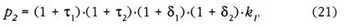

Using the same notations as before, and employing subscripts to denote the different stages, the pricing behavior of the producer in the first stage is given by

where κ1 represents his purchased inputs, which are taxed at the rate τ1 and δ1 is his markup margin, as defined earlier. Hence, equation (19) corresponds to the synthetic rule given by equation (18) with α = 1 and A = κ1·(l + δ1). As a buyer of the output of the producer in the first stage, the producer in the second stage purchases his inputs at the producer price of ρ1, that is, κ2 = ρ1 If these inputs are taxed at the rate τ2, he would set his price according to

Using equation (10), equation (11) can be rewritten as

Equation (12) is generalizable to any number of stages in a straightforward manner. If ρ ″ is the producer price after n stages, and ρ ″ denotes the corresponding producer price in the absence of the tax, then the ratio between the two would be a m...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgment

- Content Page

- I. Introduction

- II. General Concepts and Issues

- III. Domestic Consumption and Production Taxes

- IV. Income and Wealth Taxes

- V. Taxation and the Open Economy

- VI. Special Topics

- VII. Tax Reform and IMF Tax Policy Advice

- Text Tables

- Figures

- Appendix

- Footnotes