eBook - ePub

World Economic Outlook, October 1998 : Financial Turbulence in the World Economy

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

World Economic Outlook, October 1998 : Financial Turbulence in the World Economy

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access World Economic Outlook, October 1998 : Financial Turbulence in the World Economy by International Monetary Fund in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

1998eBook ISBN

9781557757739I Policy Responses to the Current Crisis

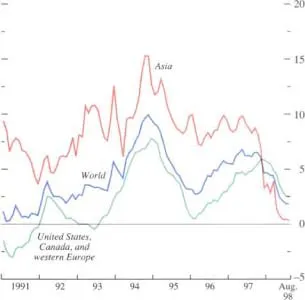

International economic and financial conditions have deteriorated considerably in recent months as recessions have deepened in many Asian emerging market economies and Japan, and as Russia’s financial crisis has raised the specter of default. Negative spillovers have been felt in world stock markets, emerging market interest spreads, acute pressures on several currencies, and further drops in already weak commodity prices. Among the industrial countries of North America and Europe, the effects of the crisis on activity have been small so far but are beginning to be fell, especially in the industrial sector (Figure 1.1). World growth of only 2 percent is now projected for 1998, a full percentage point less than expected in the May 1998 World Economic Outlook and well below trend growth. Chances of any significant improvement in 1999 have also diminished, and the risks of a deeper, wider, and more prolonged downturn have escalated.

Figure 1.1. World Industrial Production1

(Percent change from a year earlier; three-month centered moving average; manufacturing)

The worldwide slowdown in industrial activity has been most pronounced in the Asian region but is also being felt in North America and Europe.

Sources: WEFA, Inc.; OECD; and IMF, international Financial Statistics.

1 Based on data for 30 advanced and emerging market economies representing 75 percent of world output. The world total includes five emerging market countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Hungary, and Mexico) that are not included in either of the two subtotals.

* * *

Among the countries at the center of the Asian crisis, Korea and Thailand have made encouraging advances toward restoring confidence and initialing recovery, although their turnarounds remain at risk, including from the external environment. The situation in Indonesia, however, remains very difficult. Malaysia has resorted to external payments controls in an effort to insulate its economy from the regional crisis. In Japan, despite substantial fiscal stimulus and new initiatives to deal with banking sector problems, only modest recovery is expected in 1999, and significant downside risks remain. Growth in China appears to be slowing, and both the renminbi and the Hong Kong dollar have been under considerable pressure.

With Russia’s unilateral debt restructuring and the ensuing intensification of contagion, the current crisis has extended to most emerging market economies and to stock markets globally. A key problem is that financial markets tend, in the face of such a shock, to be characterized by panic and herd instinct, and, as in times of euphoria, to fail to discriminate between economies with strong and weak fundamentals. Except perhaps for central and eastern Europe, the recent upward spike in interest rate spreads indicates a sharp slowdown in capital flows to emerging market economies, including notably in Latin America. Policy responses can help to restore confidence, but even with such actions growth is likely to slow. As these economies adjust to smaller capital inflows, their trade balances will improve significantly, and coming on top of the continuing trade adjustments by the Asian crisis countries, this implies another negative shock to be absorbed by the rest of the world, primarily the United States and the European Union (EU), and also many commodity-exporting developing countries.

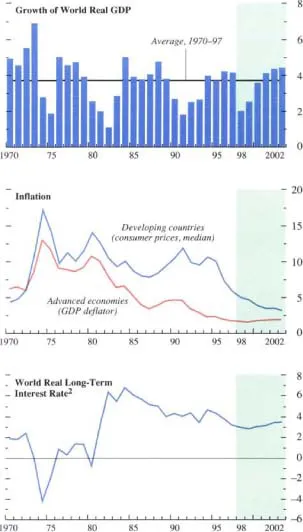

Considerable uncertainty remains about the nearterm outlook. The IMF’s revised projections (summarized in Table 2.1) are based on the assumption that financial market confidence in the Asian crisis economies will gradually return during the remainder of 1998 and in 1999, as crucial reforms are implemented. This should allow financial market pressures in these countries to continue to abate and permit the recent easing of interest rates to be sustained, which will reinforce the boost to activity from strengthened external competitiveness. In this scenario, economic recovery in Asia should be well under way by the second half of 1999. A key assumption is that Japan implements the planned fiscal stimulus and undertakes banking sector restructuring measures that bolster confidence and set the stage for an economic turnaround. The scenario also assumes that emerging market interest spreads will gradually decline and that capital flows to Latin America, central and eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Africa will recover to levels that, although lower than in the recent past, will not provoke payments crises. For the future euro area, it is expected that the momentum of recovery will be reasonably well-sustained, and for the United States, it is projected that the economy will slow markedly in a “soft landing,” without falling into recession. The resulting slowdown in world economic growth would be of the same order of magnitude as the three previous slowdowns in the past quarter century (Figure 1.2). One feature of this “baseline” scenario is that the global economy would gradually recover in the course of 1999, and return to trend growth in 2000. The risks to this projection, however, are predominantly on the downside.

Figure 1.2. World Output and Inflation1

(Annual percent change)

The Asian crisis has resulted in the fourth global economic slowdown in a quarter century.

1Shaded areas indicate IMF staff projections. Aggregates are computed on the basis of purchasing-power-parity weights unless otherwise indicated.

2GDP-weighted average of ten-year (or nearest maturity) government bond yields less inflation rates for the United States, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Canada. Excluding Italy prior to 1972.

Indeed, a significantly worse outcome is clearly possible. The potential for a broader and deeper economic downturn stems from a multitude of interrelated risks that make the current economic situation unusually fragile. Many of these risks are related to developments in international capital markets, including the danger of a prolonged retreat by international investors and banks from emerging markets, widespread financing difficulties, threats to international payments and associated disruptions to trade, and further declines in stock markets and other asset prices, with attendant losses of financial wealth and contraction of consumption and investment worldwide.

To deal with the worsening global economic situation and prospects, confidence-restoring policy adjustments are needed. In view of its pivotal role in the world economy, and especially in Asia, it is critical that Japan takes decisive action to resolve banking problems and ensure a self-sustaining recovery. The emerging Asian market economies in recession need to steadfastly address the weaknesses in policies and institutions that have been unmasked by the crisis, including the restructuring of their financial and corporate sectors. Russia needs to reestablish monetary discipline, achieve fiscal viability, restructure its banking system, and restore relations with external creditors. Other emerging market countries under stress need to forcefully address key problem areas and sources of vulnerability. The international community needs to support strong policy actions through multilateral and bilateral financial assistance. And for the United States and the future euro area, the time has come to consider a moderate easing of monetary policies to help counter the effects of the deteriorating external environment on domestic activity, and to help restore calm in global financial markets. In all countries, it is particularly important that the difficult external environment does not lead to defensive exchange rate and trade actions with negative international consequences, or to market-closing measures that would threaten countries’ longer-term economic prospects.

The current crisis has underscored the urgent need to improve the functioning of the international financial system so that countries can safely access international capital markets and investors can diversify their portfolios with a better understanding of the risks involved. This requires increased efforts to strengthen the robustness of financial institutions in both debtor and creditor countries, to enhance the transparency of the financial health of countries, corporations, and financial institutions, and to foster a realistic pricing of risks in the face of market volatility. It also requires more effective means to ensure that debtor countries face their responsibilities in dealing with the legitimate rights of creditors, that creditors participate constructively when debt workouts become necessary, and that debtors, creditors, and the international community find means to cooperate more effectively to avoid actual and quasi defaults in situations of stress.

Financial Market Developments and Risks

Following several waves of pressure in emerging markets since early 1997 emanating mainly from Asia, Russia became a new source of contagion during August. Negative sentiment in response to the devaluation of the ruble and Russia’s debt restructuring quickly spread to other emerging market countries, with risk premia increasing sharply and exchange market pressures intensifying as investors fled to quality and unloaded assets to meet margin calls. Emerging market spreads, on average, have widened to levels not seen since early 1995 at the peak of the Mexican crisis. Short-term interest rates have also risen, partly as a policy response to counter exchange market pressure.

For some time after the recent panic has subsided, emerging market countries’ external borrowing costs are likely to remain considerably higher than in most of 1996–98, and their access to international finance could be significantly reduced. Net private capital flows to emerging markets, which in the May 1998 World Economic Outlook were projected to be less than half their level in 1996 before recovering next year, are now expected to decline even more sharply in 1998, to their lowest level since 1990, and to remain weak in 1999. Latin America, which had continued securing relatively large inflows of private capital in the wake of the Asian crisis, appears to have been affected the most by the dramatic deterioration in market sentiment following the Russian crisis. A real risk is that the recent panic may fail to subside for some time, which could imply significant net outflows of foreign capital from many economies, as witnessed in the Asian crisis countries. Fears among market participants reflected in the large yield spreads seen recently could become self-fulfilling and result in prolonged disruption of international financial flows, with severely depressive effects on trade and activity. This risk can and must be contained.

Among the industrial countries, the global flight to quality has been reflected in further declines in long-term interest rates on public sector debt instruments, in many cases to levels not seen in more than 30 years. In contrast, stock market prices have declined, amid considerable volatility, as investors have marked down growth and profit expectations in the wake of the Russian crisis and fled to lower-risk assets. By mid-September, U.S. stock market prices had declined by about 15 percent from their peak in mid-July. In the major European countries, declines in stock prices from peaks at around the same time average somewhat more than 20 percent. To some extent, such corrections may be warranted in view of the earlier surge in equity prices, which may not have been fully justified by earnings prospects. However, just as equity prices may previously have overshot, the turmoil in financial market risks provoking an overreaction to recent events, with investors becoming unduly risk-averse. Significant further stock market corrections in the industrial countries might well spill over to the already depressed stock markets in Asia and other emerging markets. This could further undermine confidence and prospects for recovery.

The adjustment processes that have been triggered by the current crisis have produced a sharp widening of current account imbalances among the major industrial countries, which may also affect financial markets. The United States has so far absorbed much of the improvement in emerging Asia’s trade balance, whereas Japan’s external surplus has widened further owing to the weakness of both domestic activity and the yen, and the future euro area’s external position has remained in large surplus. Although the adjustments to the most recent bout of turmoil may be allocated more evenly between the United States and the euro area, large imbalances are likely to persist. These imbalances are not sustainable over the medium term and give rise to concerns about prospective changes in the pattern of exchange rates among the major currencies, especially if the potential downward correction of the U.S. dollar and upward correction of the yen and the euro were to occur too abruptly. It is therefore important to ensure that domestic policies in the three large currency areas during the period ahead are consistent with the need to gradually reduce external imbalances over the next several years while minimizing the risk of excessive exchange rate volatility.

Asia: Setbacks, but Progress Toward Crisis Resolution

Since the May 1998 World Economic Outlook was finalized, significant setbacks in the resolution of the Asian crisis have overshadowed the progress that has been made in some countries in the implementation of corrective policies and the stabilization of exchange rates.

First among the setbacks, data that have appeared in recent months point to significantly larger contractions in activity in much of Asia than earlier envisaged. The proximate causes include larger-than-expected declines in consumption and investment owing to losses of confidence, the widespread deflation of asset values in the region, substantial corporate debt burdens, and large reversals of capital flows that have reduced access to financing and made many firms unviable. The declines in domestic demand, in turn, have exacerbated the compression of intraregional trade, which has added to the weakness of activity both in the countries at the center of the crisis and in their trading partners in the region. In addition to these feedback effects of the ongoing contraction, the unexpected severity of the crisis could also indicate that the underlying structural weaknesses in the crisis countries may be more serious than previously thought (see Chapter III).

The evidence of greater economic weakness in Japan has had a particularly large impact because of the importance of that economy—both in terms of size and regional trade and financial links—and also the role of the yen. Thus, associated with the renewed weakness of the yen in May and early June, in particular, were further downward pressure on other Asian currencies and further declines in stock markets. Exacerbating the weakness of confidence in Japan has been the lack of convincing progress in addressing the problems of the banking sector and slowness in responding to the unexpected weakness of private demand.

Also setting back the resolution of the Asian crisis in May and June were delays in the implementation of stabilization and reform policies in Indonesia, due in part to the political instability that led to a change of government in late May. Associated with Indonesia’s political instability has been the largest currency depreciation, by far, among the Asian crisis economies.

The introduction by Malaysia in early September of exchange and capital controls may also turn out to be an important setback not only to that country’s recovery and potentially to its future development, but also to other emerging market economies that have suffered from heightened investor fears of similar actions elsewhere.

Despite these setbacks, sight should not be lost of a number of significant achievements since the beginning of the year:

- The exchange rates of all the crisis economies have strengthened from their lows, which in most cases were reached in January. The Indonesian rupiah remains deeply depreciated, but it has recovered significantly from its low reached in June. It is encouraging as well that b...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Content Page

- Assumptions and Conventions

- Preface

- Chapter I. Policy Responses to the Current Crisis

- Chapter II. The Crisis in Emerging Markets—and Other Issues in the Current Conjuncture

- Chapter III. The Asian Crisis and the Region’s Long-Term Growth Performance

- Chapter IV. Japan’s Economic Crisis and Policy Options

- Chapter V. Economic Policy Challenges Facing the Euro Area and the External Implications of EMU

- Statistical Appendix

- Boxes

- World Economic Outlook and Staff Studies for the World Economic Outlook, Selected Topics, 1992–98

- Footnotes