eBook - ePub

World Economic Outlook, May 1998 : Financial Crises: Causes and Indicators

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

World Economic Outlook, May 1998 : Financial Crises: Causes and Indicators

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access World Economic Outlook, May 1998 : Financial Crises: Causes and Indicators by International Monetary Fund. Research Dept. in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

1998eBook ISBN

9781557757401I Global Economic Prospects and Policy Considerations

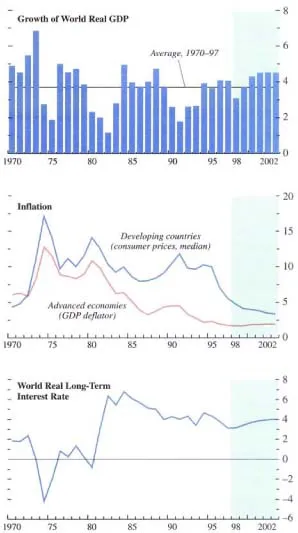

The financial turmoil in Asia that erupted in mid-1997 has abated since January, and markets have partially recovered from their troughs. Nevertheless, currency and asset values in the countries involved have been left far below precrisis levels, and considerable uncertainty remains about the resolution of the crisis and its global repercussions. It is already apparent that the crisis and its likely effects are more severe than they initially appeared and that some of the downside risks identified in the December 1997 World Economic Outlook: Interim Assessment have materialized. It still seems, however, that the global outcome will be a slowdown in economic growth that will be much less pronounced than the slowdowns of 1974–75, 1980–83, and 1990–91 (Figure 1). Important reasons why the projected global slowdown is relatively mild include the solid prospective growth of domestic demand in most industrial countries and the limited spillover effects of the Asian crisis in other regions. In the medium term, global economic growth is still projected to exceed the average rate seen since 1970, reflecting a continued strengthening of growth in the countries in transition and maintenance of the relatively strong performance of the developing world in the early and mid-1990s.

Figure 1. World Output and Inflation1

(Annual percent change)

The Asian crisis is expected to result in only a moderate and short-lived slowdown in world growth.

1Shaded areas indicate IMF staff projections. Aggregates are computed on the basis of purchasing power parity (PPP) weights unless otherwise indicated.

This issue of the World Economic Outlook projects world output growth in 1998 at just over 3 percent, compared with projections of 3½ percent in the December Interim Assessment and 4¼ percent in the October 1997 World Economic Outlook (see Table 2 in Chapter II). The largest downward revisions have been for the three economies most affected by the crisis—Indonesia, Korea, and Thailand—where the drying up of private foreign financing, together with the large currency depreciations and declines in asset prices that have occurred, is causing sharp contractions of domestic demand, which will be only partially counterbalanced by increased net exports. Similar forces, but on a smaller scale, have also lowered near-term growth prospects for Malaysia, the Philippines, and a number of other countries in east Asia. All these countries will experience sharp slowdowns of domestic demand and imports in 1998, with real GDP likely to decline in the countries worst hit. In Indonesia, continuing uncertainties about the course of policies have hindered a decisive turnaround in financial markets, but elsewhere among the countries worst affected there appears already to have been some improvement in sentiment. Although there are painful adjustments yet to come, there are grounds for expecting a continuing recovery of confidence in these economies in the year ahead, followed by a moderate pickup in activity in 1999. These expectations are based on increasing evidence of the commitment of the authorities of these countries to the implementation of needed stabilization and reform measures, and on the economies’ strong underlying growth potential, which should reassert itself once earlier excesses have been corrected, critical weaknesses have been addressed, especially in the financial sector, and confidence has been restored.

Contagion and spillover effects have altered the outlook for other emerging market countries. Reduced availability of foreign financing, increased interest spreads on foreign borrowing, lower stock market prices, and policy tightenings to reduce vulnerability to disruptive changes in market sentiment have weakened near-term growth prospects widely, including in some of the transition countries. In general, the adverse effects seem likely to be moderate, with growth remaining positive, but there are risks of a sharper slowdown if the crisis in Asia were to deepen. The effects of the crisis are also being felt through weaker commodity prices, including for oil. For developing and transition countries that are net importers of these products, there will be helpful terms of trade gains, but for many net exporters there will be negative effects on growth, and on current account and fiscal positions, that will be significant in some cases.

Among the advanced economies, the near-term outlook for Japan has deteriorated further. Though exacerbated by the difficulties of many of its Asian trading partners, the faltering of Japan’s recovery last year can be largely attributed to homegrown problems, including financial sector weaknesses and bad-loan difficulties, delays in the implementation of structural reforms needed to reinvigorate the economy, and a large withdrawal of fiscal stimulus in 1997 when the recovery was still fragile. In spite of measures that have been taken to address financial sector problems and to support domestic demand, overall activity is now projected to stagnate in 1998. Further measures are urgently needed to bring about an early resumption of growth.

Fortunately, growth in North America and western Europe has been well sustained and appears likely to remain so in the period ahead. Domestic demand conditions—robust in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, and strengthening in much of continental western Europe—will facilitate the adjustment of current account positions that is needed in the Asian emerging market countries because of the sharp declines in capital inflows. The adjustment process in the emerging market countries will reduce net exports from North America and Europe, and also reduce inward foreign direct investment (from Asian companies in difficulty) in some cases. But on the other hand, the redirection of financial investments toward mature markets has helped to reduce real interest rates, while terms of trade gains will also help to support domestic demand. It remains to be seen how confidence will be affected as export orders from Asia and other emerging markets decline, and as some financial institutions feel the effects of difficulties experienced by Asian borrowers. On balance, the Asian crisis is likely to exert a moderate contractionary and disinflationary effect on the industrial, as on other, economies, thus reducing the risk of overheating in those countries operating at high levels of resource utilization, in particular the United States.

Although the threat to global growth from the Asian crisis still appears to be limited, there are clearly downside risks. Policy slippages in the crisis economies may further undermine confidence, unsettle financial markets, and delay recovery. The crisis, together with recent commodity price movements (particularly the decline in oil prices) will bring about some large adjustments in external positions, with painful consequences for some countries, and it is important that countries whose external balances deteriorate do not impose barriers to trade or allow competitive currency depreciations. Such defensive reactions would be counterproductive, slowing the adjustment process of the countries in crisis and impairing growth worldwide.

There are also risks arising from developments in foreign exchange and financial markets in the industrial countries. Equity markets in many countries have recently risen to new highs, and the U.S. dollar has strengthened further. The redirection of financial flows toward mature markets may have contributed to these developments. But with the current account deficit of the United States expected to widen substantially this year, there is the potential for a change in sentiment toward the dollar at some future stage, which would reverse one of the temporary factors that has been helping to hold down U.S. inflation. If world commodity prices were to recover at the same time and labor market pressures continued to push up wage growth, the Federal Reserve could face the need for a significant tightening of monetary conditions, and both bond and stock markets might be subject to significant corrections. The strength of sterling points to similar concerns in the case of the United Kingdom. Thus, while the Asian crisis suggests a need for monetary conditions in the industrial countries to be somewhat easier in the period ahead than would otherwise have been warranted, policymakers will need to remain vigilant to prospective changes in inflationary pressure, including those arising from financial market developments. Further risks arise from the financial sector difficulties and fragilities being experienced in many emerging market countries and in some advanced economies, especially Japan.

This report extends and updates (in Chapter II) the analysis in the Interim Assessment of the global ramifications of the Asian crisis. Whereas the Interim Assessment discussed the factors contributing to the buildup to the crisis and examined the unfolding of the episode, this issue of the World Economic Outlook draws lessons (in Chapter IV) more broadly, from the most recent and earlier financial crises; one of the major policy questions in this context—the choice of exchange rate regime in emerging market economies—was considered in depth in the October 1997 World Economic Outlook. This issue of the World Economic Outlook also examines (in Chapter III) how exchange rate developments, particularly among the major currencies, are related to international divergences in business cycles—a question relevant to the assessment of the recent configuration of exchange rates among the major currencies. The most important development in foreign exchange markets in the coming year is likely to be the scheduled start of Stage 3 of European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), which was treated extensively in the October 1997 World Economic Outlook; an appendix to this chapter examines some aspects of recent progress in this venture. Finally, this issue (in Chapter V) examines progress with fiscal reform in transition countries—an area where some of these countries’ greatest policy challenges lie.

The Asian Crisis

The economies of east Asia at the center of the recent crisis have been some of the most successful emerging market countries in terms of growth and gains in living standards. With generally prudent fiscal policies and high private saving rates, these countries had become a model for many others. That this region might become embroiled in one of the worst financial crises in the postwar period was hardly ever considered—within or outside the region—a realistic possibility. What went wrong? Part of the answer seems to be that these countries became victims of their own success. This success had led domestic and foreign investors to underestimate the countries’ economic weaknesses. It had also, partly because of the largescale financial inflows that it encouraged, increased the demands on policies and institutions, especially but not only in the financial sector; and policies and institutions had not kept pace. The fundamental policy shortcomings and their ramifications were fully revealed only as the crisis deepened. Past success may also have contributed to a tendency by policymakers to deny the need for action when problems first became apparent.

Several factors—mainly domestic but also external, operating to different degrees in different countries, and exacerbated by contagion and spillovers among the countries involved—seem to have contributed to the dramatic deterioration in sentiment by foreign and domestic investors. As discussed in the Interim Assessment, the key factors appear to have been, first, the buildup of overheating pressures, which had manifested themselves in large external deficits and inflated property and stock market values; second, the maintenance for too long of pegged exchange rate regimes, which complicated the response of monetary policy to overheating pressures, and which came to be viewed as implicit guarantees of exchange value, encouraging external borrowing—often at short maturities—and leading to excessive exposure to foreign exchange risk in both the financial and corporate sectors; third, in financial systems, weak management and poor control of risks, tax enforcement of prudential rules and inadequate supervision, and associated relationship and government-directed lending practices that had led to a sharp deterioration in the quality of banks’ loan portfolios; fourth, problems of data availability and lack of transparency, which hindered market participants from maintaining a realistic view of economic fundamentals, and at the same time added to uncertainty; and finally, problems of governance and political uncertainties, which exacerbated the crisis of confidence, the reluctance of foreign creditors to roll over short-term loans, and the downward pressure on currencies and stock markets.

External factors also played a role. Large private capital flows to emerging markets were driven, to an important degree, by an underestimation of risks by international investors, as they searched for higher yields during a period when investment opportunities appeared less profitable in Japan and Europe owing to sluggish economic growth that necessitated low interest rates. With exchange rates pegged to the U.S. dollar in several cases, the wide swings in the yen/dollar exchange rate between 1994 and 1997 also contributed to the buildup to the crisis through shifts in international competitiveness that proved unsustainable. In particular, losses in competitiveness associated with the dollar’s appreciation, particularly against the yen, from mid-1995, contributed to the export slowdown experienced by a number of countries in the region in 1996–97. Finally, international investors—mainly commercial and investment banks—may in some cases have contributed significantly to the downward pressure on the currencies in crisis, alongside domestic investors and residents seeking to hedge their foreign currency exposures; but hedge funds appear to have played a significant role only in the case of the Thai bhat (Box 1). Many foreign investors have taken substantial losses.

To contain the economic damage caused by the crisis, the countries directly affected have needed to implement corrective measures, and the international community led by the IMF has provided financial support for policy programs in the countries worst hit—Indonesia, Korea, and Thailand. Unfortunately, in these cases the authorities’ initial hesitation in the implementation of appropriate reforms and other confidence- repairing measures worsened the crisis by causing currency and stock markets to decline well beyond what was justified by any reasonable reassessment of economic fundamentals, even in the light of the crisis. This overshooting in financial markets exacerbated the panic and added to the difficulties in both the corporate and financial sectors, especially by swelling the domestic currency value of foreign debt. More recently, however, while uncertainties have persisted in Indonesia, it is clear that elsewhere commitments to implement the necessary reforms and adjustment measures have strengthened substantially.

Box 1. The Role of Hedge Funds in Financial Markets

Bouts of turbulence in international financial markets in recent years have drawn attention to the role played by institutional investors, especially hedge funds. Following both the 1992 crisis in the European exchange rate mechanism (ERM) and the turbulence in international bond markets in 1994, and again in the wake of the turmoil in financial markets in east Asia in mid-1997, it was suggested that hedge funds precipitated major movements in asset prices either directly through their own transactions or indirectly via the tendency of other market participants to follow their lead. Because information on hedge funds’ activities is limited, IMF staff undertook a study of their role in recent market developments.1 This box summarizes the main findings.

What Are Hedge Funds?

Hedge funds are private investment pools, often domiciled offshore to capitalize on tax and regulatory advantages. In the United States, they typically offer their shares in private placements and have fewer than 100 high-net-worth investors in order to make use of exemptions to regulations under the Securities Act of 1933, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, and the Investment Company Act of 1940. They are managed on a fee-for-performance basis; typically, management is rewarded by a 1 percent management fee and 20 percent of profits, although management and investment fees vary. Most funds require shareholders to provide advance notification if they wish to withdraw funds: notice can vary from 30 days for funds with more liquid investments to three years for other funds.

Practices, however, vary enormously. Market participants distinguish two main classes of funds: macro hedge funds, which take large directional (unhedged) positions in national markets based on analyses of macroeconomic and financial conditions; and relative value funds, which make bets on the relative prices of closely related securities (treasury bills and bonds, for example) and are less exposed...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Assumptions and Conventions

- Preface

- Chapter I. Global Economic Prospects and Policy Considerations

- Chapter II. Global Repercussions of the Asian Crisis and Other Issues in the Current Conjuncture

- Chapter III. The Business Cycle, International Linkages, and Exchange Rates

- Chapter IV. Financial Crises: Characteristics and Indicators of Vulnerability

- Chapter V. Progress with Fiscal Reform in Countries in Transition

- Annexes

- Statistical Appendix

- Tables

- World Economic Outlook and Staff Studies for the World Economic Outlook, Selected Topics, 1992–98

- Footnotes