eBook - ePub

World Economic Outlook, October 1997 : EMU and the World Economy

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

World Economic Outlook, October 1997 : EMU and the World Economy

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access World Economic Outlook, October 1997 : EMU and the World Economy by International Monetary Fund. Research Dept. in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

1996eBook ISBN

9781557756107I Global Economic Prospects and Policies

Industrial Countries

In the industrial countries, there are promising signs that economic activity will turn out to be stronger in 1997 than during the past year, when growth slowed sharply in many countries.1 At the same time, inflation is likely to remain subdued while external imbalances are expected to diminish further in a number of cases. For the United States, the slowdown in 1995 was needed to reduce the risk of overheating after the strong performance of 1994, which brought the economy to a high rate of resource utilization. More recently, activity has again picked up, partly in response to the easing of monetary conditions that began in mid-1995. In Europe—with the main exception of the United Kingdom, where growth had also been above trend—the slowdown in growth was decidedly unwelcome as recoveries from the trough of the 1992–93 recession were incomplete and unemployment had remained high. Since the beginning of 1996, however, conditions for a renewed strengthening of activity have improved as monetary conditions have generally eased, as long-term interest rates remain well below their levels in late 1994 and the first half of 1995, and as overstocking appears to have been corrected somewhat. Moreover, with greater convergence of economic and policy fundamentals within Europe, exchange rates have returned to levels more consistent with balanced growth following the misalignments that arose in the spring of 1995 when the deutsche mark (together with the yen) appreciated sharply against the U.S. dollar and several other currencies. In Japan, in contrast to the moderation of growth elsewhere in 1995, the recovery has gained momentum, with confidence gradually recovering as the yen depreciated from the excessively high values reached in the early part of last year.

Box 1. Policy Assumptions Underlying the Projections

Fiscal policy assumptions for the short term are based on official budgets adjusted for any deviations in outturn as estimated by IMF staff and also for differences in economic assumptions between IMF staff and national authorities. The assumptions for the medium term take into account announced future policy measures that are judged likely to be implemented. In cases where future budget intentions have not been announced with sufficient specificity to permit a judgment about the feasibility of their implementation, an unchanged structural primary balance is assumed. For selected industrial countries, the specific assumptions adopted are as follows.

United States: For the period through FY1999, fiscal revenues and outlays at the federal level are based on the administration’s March 1996 budget proposal (as updated in the July 1996 Mid-Session Review of the 1997 Budget), after adjusting for differences between the IMF staff’s macroeconomic assumptions and those of the administration. From FY 2000 onward, the federal government primary balance as a proportion of GDP is assumed to remain unchanged from its projected FY 1999 level.

Japan: Measures that have already been announced are assumed to be implemented over the medium term. These measures include an increase in the consumption tax rate from 3 percent to 5 percent in 1997 and a simultaneous end to the temporary income tax cut, implementation of the 1994 pension reform plan, and the medium-term public investment plan.

Germany: The 1996 projection for the general government is based on the 1996 federal budget and recent official estimates for the other levels of government, adjusted for differences in macroeconomic projections. The 1997 projections are based on official tax estimates and envisage implementation of most of the government’s proposed fiscal package. Elements of the package that have gained the requisite agreement (e.g., from the unions and the Bundestag) have been incorporated, while measures that still need Bundesrat approval or lack specificity at the Lander level have not been fully taken into account. Projections for 1998 and beyond are predicated on an unchanged structural primary balance.

France: The projections for both 1996 and 1997 take into account policy measures that have already been implemented. In addition, it is assumed that the government’s plans for the 1997 budget of the state (a freeze in nominal expenditure yielding an adjustment of about ½ of 1 percent of GDP) will be fully achieved, given the strong commitment to meeting the criteria for European Economic and Monetary Unit (EMU). As regards social security spending in 1997, the projections assume that Parliament (using the new powers conferred by the constitutional amendment adopted earlier this year) will set a ceiling consistent with the government’s overall objectives.

Italy: The projections take into account policy measures that have already been implemented, including the June 1996 supplementary package. In addition, it is assumed that the measures announced in the 1997–99 plan are fully implemented and yield the officially estimated amounts. Projections beyond 1999 assume an unchanged structural balance.

United Kingdom: The budgeted three-year spending ceilings are assumed to be observed. Thereafter, noncyclical spending is assumed to grow in line with potential GDP. For revenues, the projections incorporate, through the three-year budget horizon, the announced commitment to raise excises on tobacco and road fuels each year in real terms; thereafter, real tax rates are assumed to remain constant.

Canada: Federal government outlays for departmental spending and business subsidies conform to the medium-term commitments announced in the March 1996 budget. Other outlays and revenues are assumed to evolve in line with projected macroeconomic developments. The unemployment insurance premium, however, is assumed to fall in 1998/99 to a level that is consistent with an unchanged surplus in the unemployment insurance account. The fiscal situation of the provinces is assumed to be consistent with their stated medium-term deficit targets.

Spain: Projections for 1996–97 incorporate the multiyear expenditure control agreements in the areas of public sector wages and employment, health care, and regional and local governments; additional cuts announced in May; and the economic liberalization, tax measures, and wage freeze announced in June and July. For 1997, the income tax schedule and excise taxes are assumed to be adjusted in line with inflation. The projections do not take into account the implications for 1996–97 of the recently discovered large public expenditure overruns in 1995.

Netherlands: Projections assume continued adherence to the government’s medium-term expenditure path for the central government and social security. While the authorities have not specified a general government deficit target for 1997, their 1997 expenditure ceilings for central government and social security that were decided in the spring of 1996 provide scope for a deficit well under 3 percent of GDP.

Belgium: Projections for 1996 are based on the budget and the spring budget control exercise. For 1997, IMF staff estimates reflect the general government deficit ceiling of 3 percent of GDP included in the framework law passed by Parliament in July 1996 that gives the government broad powers to achieve participation in EMU (recent pronouncements by the authorities have signaled a desire for a deficit of 2.8 percent of GDP).

Sweden: The medium-term projections are based on the government’s multiyear consolidation program approved by Parliament in 1995 and additional measures taken in April 1996.

Greece: Projections for 1996 reflect the IMF staff’s assessment of the outcome of the official budget. Measures to meet the targets of the convergence plan are still being defined in the 1997 budget under preparation, and the projections at this stage are based on IMF staff estimates of current services.

Portugal: Projections for 1996 are based on implementation to date of the official budget. Preparation of the 1997 budget (which will aim at a deficit of not more than 3 percent of GDP) is currently under way, and the projections for 1997 and beyond are at this stage based on an unchanged structural primary balance.

Switzerland: Projections for 1996–99 are based on official estimates for current services. Thereafter, the general government structural primary balance is assumed to remain constant.

Australia: Projections for the Commonwealth government are based on the 1996/97 budget, adjusted for any differences between the economic projections of the staff and the authorities. Unchanged policies are assumed for the state and local government sector from 1996.

* * *

Monetary policy assumptions are based on the established framework for monetary policy in each country, which in most cases implies a nonaccommodative stance over the business cycle. Hence, it is generally assumed that official interest rates will firm when economic indicators, including monetary aggregates, suggest that inflation will rise above its acceptable rate or range and ease when the indicators suggest that prospective inflation does not exceed the acceptable rate or range and that prospective output growth is below its potential rate. For the exchange rate mechanism (ERM) countries, which use monetary policy to adhere to exchange rate anchors, official interest rates are assumed to move in line with those in Germany, except that progress on fiscal consolidation may influence interest differentials relative to Germany. On this basis, it is assumed that the London interbank offered rate (LIBOR) on six-month U.S. dollar deposits will average 5.6 percent in 1996 and 6 percent in 1997; that the six-month LIBOR rate in Japan will average 1 percent in 1996 and 2.4 percent in 1997; and that the three-month interbank deposit rate in Germany will average 3.3 percent in 1996 and 3.8 percent in 1997.

Inflation in the industrial world has been generally well contained in recent years and is no immediate threat to sustained growth in most countries. But as discussed further below, monetary authorities will, of course, need to remain vigilant to incipient price pressures as growth continues or strengthens. (The monetary and fiscal policy assumptions underlying the projections are summarized in Box 1.) Of continuing concern, however, is the need shared by most industrial countries to make further progress toward substantially reducing their fiscal imbalances over the medium term. Structural (i.e., cyclically adjusted) deficits have only been brought down from 3½ percent of GDP in 1992 to 2½ percent of GDP in 1995 for the industrial countries as a group, and the financing of fiscal deficits remains a source of pressure on world real interest rates, keeping the level of private investment and potential future growth below what otherwise could be achieved. A growing number of countries, however, are setting targets for substantially eliminating their fiscal shortfalls over the medium term. These consolidation efforts appropriately are focused on the need to contain the level and growth of public expenditure, which may ultimately permit reductions in tax burdens. There is also increased awareness of the need to address early on the problem of unfunded pension liabilities, which threaten to exacerbate pressures on public finances as populations age in coming decades (see Chapter III of the May 1996 World Economic Outlook). In many countries, however, the debate about pension reform and the search for solutions has only just begun.

Most of the largest fiscal imbalances are suffered by members of the European Union (EU), including some of those countries that have experienced the highest unemployment rates and the weakest growth performance in recent years. It is generally recognized that progressive elimination of fiscal imbalances is necessary for an improvement in growth performance over the medium term. The priority that has now been given to fiscal consolidation has already begun to yield benefits in reducing risk premiums in long-term interest rates, in improving confidence, and in strengthening medium-term growth prospects, particularly in those countries where financial markets previously indicated some lack of confidence in government policies. The attention being given to fiscal consolidation also reflects the desire to meet the objective of keeping fiscal deficits within the Maastricht Treaty reference value of 3 percent of GDP by 1997, the test year for deciding which member countries meet the criteria for participation in the third and final stage of EMU beginning in 1999.

While the weakness of activity in early 1996 would appear to militate against the pursuit of specific fiscal targets defined in actual rather than cyclically adjusted or structural terms, the legacy of excessive fiscal imbalances in many European countries suggests that any significant backsliding from announced consolidation efforts could have severe implications for interest rates and financial market confidence, especially since it might derail the EMU process. Not only does the maintenance of an adequate pace of consolidation offer the best prospect for a sustained improvement in economic performance over the medium term, but also the short-term costs may be smaller than those arising from failure to address adequately the persistently large deficits. At the same time, it is important to avoid aggravating a difficult situation through unduly pro-cyclical fiscal policies. If recent economic weakness were to be prolonged, it would be necessary to allow fiscal policy to provide automatic stabilizers for activity, but only in those countries that are making convincing and adequate progress in reducing structural imbalances (Chart 2). To foster greater fiscal discipline in Stage 3 of EMU, it is encouraging that the EU is considering an agreement whereby countries would aim for a budgetary position close to balance over the medium term. This should provide a basis for allowing automatic stabilizers to operate without budget deficits exceeding 3 percent of GDP during a normal business cycle.

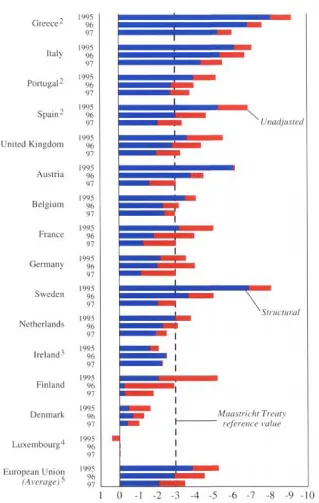

Chart 2. European Union: General Government Budget Positions1

(In percent of GDP)

Expected progress toward reducing underlying budgetary imbalances is masked to some extent by large cyclical components in fiscal deficits.

1 IMF start estimates and projections. The ordering of countries is based on the projected unadjusted budget positions in 1997, except that where the differences between projections are not significant the ordering is alphabetical.

2 The estimates differ from those of national authorities (shown in Table at least in part because sufficient information on the measures to be proposed in the 1997 budgets is not yet available. See Box 1 for details regarding the IMF staff’s fiscal assumptions.

3 The unadjusted budget position for Ireland in 1996 is not shown separately because it is about equal to the structural balance, reflecting the fact that output is close to potential.

4 Structural budget positions are unavailable and unadjusted budget positions are expected to be in approximate balance in 1996–97.

5 Excludes Luxembourg.

For many countries, particularly in Europe, fiscal imbalances are related to shortcomings in the functioning of labor markets, which have resulted in a dramatic upward trend in unemployment over the past twenty-five years. As much as 8 to 9 percentage points of the EU’s current unemployment rate of over 11 percent is widely considered to be structural in the sense that it is unlikely that it could be absorbed through cyclical recovery alone, without significant inflationary risks. Together with discouraged job seekers and heavy resort to early retirement, these high rates of unemployment represent a considerable underutilization of labor resources, which has reduced potential output and exacerbated budgetary pressures through revenue losses and outlays for income support. Clearly, a substantial reduction in this underutilization through appropriate labor market reforms would go a long way toward addressing Europe’s fiscal shortfalls.

Many economists and policymakers agree on the root causes of rising structural unemployment and on the types of reform that are needed to reverse it. Much remains to be done to tackle the problem, however, and it has proved extremely difficult to mobilize public support for the necessary reforms. In many countries, there is great reluctance to modify labor market regulations, benefits, and privileges that are widely perceived to be social achievements, but which contribute to persistently high unemployment and social exclusion by keeping labor costs above warranted levels for low-productivity workers and by reducing incentives to work and to create jobs. New Zealand and the United Kingdom are the most prominent examples of countries that have begun to reduce their structural unemployment rates. Most other countries have introduced some reforms aimed at reducing overly generous levels of unemployment compensation, tightening eligibility criteria, reducing taxes on employment, restraining increases in minimum wages, or facilitating restructurings and layoffs—and thereby hirings. The reforms in many countries, however, have been mostly piecemeal, and the beneficial effects of progress in one area have often been hampered by new or deeply ingrained distortions in other areas.

The essential aim of labor market reforms must be to allow market forces a greater role in helping to clear the labor market at much lower levels of unemployment. Since this may well result in lower real wages for some skill categories, governments, in Europe and Canada, in particular, are faced with the challenge of also reforming tax and transfer systems so that they may better meet equity objectives and safeguard a reasonable level of social protection without the negative implications for incentives and employment that are associated with present arrangements. Enhanced training and education are also needed in all countries to alleviate poverty an...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Copyright Page

- Content Page

- Assumptions and Conventions

- Preface

- Partnership for Sustainable Global Growth

- Chapter I. Global Economic Prospects and Policies

- Chapter II. World Economic Situation and Short-Term Prospects

- Chapter III. Policy Challenges Facing Industrial Countries in the Late 1990s

- Chapter IV. Financial Market Challenges and Economic Performance in Developing Countries

- Chapter V. Long-Term Growth Potential in the Countries in Transition

- Chapter VI. The Rise and Fall of Inflation—Lessons from the Postwar Experience

- Annexes

- Statistical Appendix

- Tables

- Footnotes