eBook - ePub

Changing Customs : Challenges and Strategies for the Reform of Customs Administration

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Changing Customs : Challenges and Strategies for the Reform of Customs Administration

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Changing Customs : Challenges and Strategies for the Reform of Customs Administration by Michael Keen in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

2003eBook ISBN

9781589062115CHAPTER 1. The Future of Fiscal Frontiers and the Modernization of Customs Administration

One of the great ironies of intellectual history is that Adam Smith, the apostle of free trade, ended his days as a Comptroller of Customs. By the same token, it may seem strange that the International Monetary Fund (IMF), committed to the principles of free trade, should devote a good deal of its technical assistance activities to strengthening the performance of customs administrations. In each case, however, the explanation is easily found. For Smith, the position of Comptroller at Kircaldy, a post his father had also held, was an attractive sinecure (as customs posts continue to be in all too many countries). For the IMF, the support of improvement in customs administration reflects the recognition that although customs administration would wither away in an ideal world, in practice trade taxes are likely to be a significant source of revenue for many of its members, especially developing countries, for the foreseeable future; and that if trade taxes are to be levied, it is best that this be in a way that does least collateral damage to international trade flows.

This book describes and reviews the key challenges that arise in ensuring that customs administrations perform their core revenue functions with minimal adverse impact on trade activities and the allocation of resources—and suggests how they can be addressed. More particularly, it provides a distillation of the central lessons that the IMF—and especially the Fiscal Affairs Department (FAD), which takes the lead in matters of customs administration—has learned from its extensive technical assistance activities in this area. The central theme of this book, as of all FAD’s work in this area, is the potential for considerable benefit, to both public and private sectors, from modernizing customs administration in the light of continuing and rapid changes in the pattern, extent, and nature of international trade.

This chapter provides the broad context for this concern with modernization. Section A explains why modernization of customs administration is so vital. It might be thought that with the trend toward trade liberalization over recent decades the revenue role of customs is gradually but surely fading away. But this is far from being the case: many current developments make the role of the customs administration both more important and harder. Section B then describes the essence of modernization, which later chapters elaborate upon.

A. Customs Administration and the Future of Fiscal Frontiers

History and geography combine to select and create border posts as convenient points at which to control the movement of goods and people, managing the interface between distinct national legislations and identities. Control of the movement of people is generally the function of a distinct immigration service. The primary tasks of customs administrations relate to the movement of goods. The many such functions of this kind include protection against terrorist activities (a role that has come to prominence in the United States, in particular, after the attacks of September 11, 2001), the enforcement of quantitative restrictions on imports or exports of particular commodities (perhaps from particular countries), the detection and seizure of prohibited items, the enforcement of sanitary and phytosanitary restrictions and of rules relating to endangered species and intellectual property rights, the implementation of exchange restrictions (becoming less important), checking for movements of large quantities of cash suggestive of money laundering (becoming more important), and the collection of revenues from import tariffs and export taxes.

This book is concerned only with revenue-related aspects of the work of customs administration, and with particular reference to developing countries, where trade taxes remain an important source of government revenue. The links between the various functions just described always need to be borne in mind, however. At the most general level, the need for border controls to serve these other purposes may reduce the costs, and hence increase the attractions, of using them also to raise revenue; conversely, countries that for wider political reasons wish to remove frontiers between themselves—historically a key step in the process of building federations and nations—will find that tariffs too must be dismantled. In more practical terms, there is little gain in speeding up the clearance of goods for tariff purposes if their onward movement is further delayed by, for example, lengthy security or health inspections.1

The focus of the book being on the role of customs administration in relation to fiscal frontiers—the interface, physical and otherwise, between the tax and tariff systems of different countries—a key strategic issue is the likely pattern of developments in the nature of those frontiers. Many current trends suggest that, despite continued measures of trade liberalization—indeed to some degree because of them—that role is unlikely to become any less important in the foreseeable future, and is likely to become even more challenging.

The continuing growth of international trade

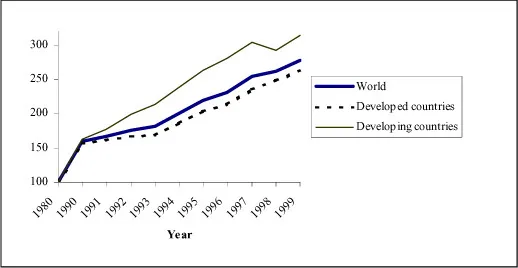

The workload of the customs administration is largely driven simply by the magnitude of the trade flows with which it must cope. As shown in Figure 1.1, between 1980 and 1999 the volume of all merchandise exports grew by over 250 percent. Their value rose even more markedly, by 280 percent. These increases outstripped that of world GDP, which rose by 164 percent. They have also been even more marked for developing countries than for developed: developing countries’ trade more than tripled in volume over the last 20 years.

Figure 1.1. The Growth of Trade Volumes, 1980–1999 (1980 = 100)

Source: UNCTAD (2001).

Note: Figures are averages of export and import volumes.

These increases in both the absolute and the relative importance of trade flows doubtless reflect, in part, the impact of trade liberalization. But, short of complete free trade, the work involved in processing them is to a large degree independent of the level of the tariffs applied (though the amount of resources optimally allocated to customs administration is not): the steps that must be followed to impose a 5 percent tariff are essentially the same as those required for a 40 percent tariff. Moreover, so long as some commodities bear a tariff, even those that do not require some control in order to prevent evasion of trade taxes through misdeclaration. The increased use of just-in-time methods of production has further increased the importance of timely and effective administration of customs requirements, and the increasing importance of small consignments—requiring at least some monitoring—has added to the work pressures.

It may be that much of the growth in world trade in coming years will be in relation to services, for which the role of customs is generally limited (for the simple reason that intangibles cannot be intercepted at borders). But there is every sign that the secular trend increase in merchandise documented above will continue. The challenges of processing remaining trade taxes with the minimum disruption to trade are likely, if anything, to intensify.

Tariffs will remain an important source of revenue

Although there has been significant liberalization of trade over recent decades, in many countries trade tax rates continue to be quite high, and the receipts they yield are a key component of the public finances.

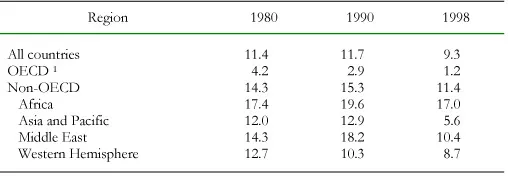

Table 1.1 shows the development of collected tariff rates—tariff revenues as a percentage of import value—over the last 25 years. While these have more than halved in the developed countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), elsewhere in the world the reduction has been less marked. In particular, the average effective tariff rate in Africa has barely changed.2 These averages conceal, however, considerable variation in developments across countries. The significant reduction in the average collected rate for the Middle East over the 1990s, for example, reflects marked reductions in Egypt and Pakistan. Elsewhere in the region the collected rate hardly fell, or even slightly increased.

Table 1.1. Collected Tariff Rates by Region

(Unweighted averages, percent)

Sources: Various issues of IMF, Government Financial Statistics and World Economic Outlook; OECD, Revenue Statistics.

1 Excluding Czech Republic, Hungary, Luxembourg, and Poland.

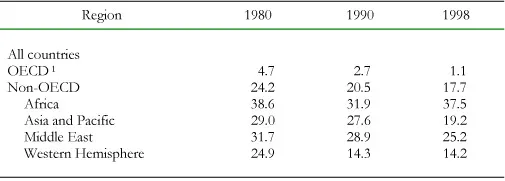

The continuing importance of the revenue that governments collect on trade—both imports and exports3—is shown in Table 1.2. In Africa, more than one-third of total revenue still comes from trade taxes, whose relative importance actually increased over the 1990s. Elsewhere in the world there is a clear downward trend, but reliance still remains high: one-fifth of all revenues in Asia and the Pacific, and one-quarter in the Middle East.

Table 1.2. Trade Taxes as a Share of Total Tax Revenue

(Unweighted averages, percent)

Sources: Various issues of IMF, Government Financial Statistics and World Economic Outlook; OECD, Revenue Statistics.

1 Excluding Czech Republic, Hungary, Luxembourg, and Poland.

These figures do not mean, it should be emphasized, that there has not been significant trade liberalization, and this is so even in countries where the collected tariff rate remains high. Trade liberalization is not simply a matter of cutting tariffs and export taxes, but of lightening a whole range of restrictions on trade flows. One key element, in particular, has been the conversion of quantitative restrictions on imports into explicit tariffs, a measure that—in so far as revenue was not collected from quotas by selling licenses to import—tends to raise both collected tariff rates and trade tax revenue. Moreover, if motives of protectionism lead to tariffs being set about revenue-maximizing levels—prohibitively high tariffs, most obviously, raise no revenue—small reductions in their level will actually lead to an increase in tariff revenues. While trade liberalization must thus ultimately lead to a decline in trade tax revenues, in the early stages, at least, revenues may not be greatly affected, as Ebrill, Stotsky, and Gropp (1999) document.4

For the foreseeable future, in any event, the central lesson is clear: for many developing countries, and especially the poorest of them, tariff revenue will continue to be a core component of government finances for many years to come.

Customs’ role in the collection of domestic taxes

Customs administration also has a key role to play in enforcing fiscal frontiers between domestic tax systems.

The role in relation to direct taxes is limited. Some developing countries levy withholding taxes on imports and/or exports, treating this as partial or complete discharge of income tax liability. The resolution of transfer pricing disputes sometimes revolves around establishing proper valuation of imports, though the more problematic cases concern the treatment of trade in intangibles not monitorable at the frontier.

In relation to indirect taxes, on the other hand, customs administration has a crucial role. These taxes are generally levied on the destination basis, meaning that all domestic consumption of any given commodity—whether domestically produced or imported—is taxed at the same rate, while exports leave a country tax-free.5 It then falls to customs to play a pivotal part in ensuring that commodities entering a country are brought into tax, and that commodities claimed to be exported (and so relieved of domestic tax) are indeed transferred abroad, and not diverted to the domestic market.

In this respect, the importance of customs has actually been increased by the remarkable spread of the value-added tax (VAT), even though this has in many cases been adopted as a conscious adjunct to trade liberalization.6 The essence of the VAT—now applied in over 120 countries, and adopted by many developing countries over the last decade or so—is that tax is charged at each stage of production; taxes paid on inputs are credited against tax due on output, or refunded to the extent that they exceed output tax. This means that VAT needs to be charged on all imports, whether for final consumption or use as inputs.7 As a consequence, and as shown in Table 1.3, much VAT revenue is actually collected on imports: more than half in almost all the countries shown (and there is no reason to suppose these to be exceptional), and often considerably more. Much of this revenue will be credited or refunded further down the production chain; but the key point is that it is at the border that governments typically first get their hands on much of their VAT revenues.

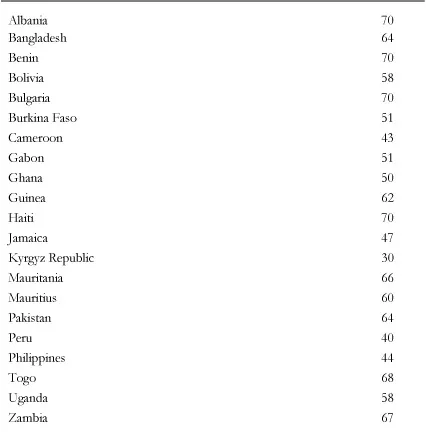

Table 1.3. VAT on Imports as a Share of All VAT Revenues

Source: Ebrill and others (2001); IMF staff estimates.

On the export side too the presence of the VAT lends added importance to customs administration; one of the most attractive and common forms of VAT fraud is to falsely claim that commodities have been exported, so enabling a dishonest trader not merel...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Chapter 1. The Future of Fiscal Frontiers and the Modernization of Customs Administration

- Chapter 2. Trade Policy and Customs Administration

- Chapter 3. Strategy for Reform

- Chapter 4. Simplifying Procedures and Improving Control Prior to Release of Goods

- Chapter 5. Post-Release Verification and Audit

- Chapter 6. Customs Valuation

- Chapter 7. Customs Duty Relief and Exemptions

- Chapter 8. Transit

- Chapter 9. Computerization of Customs Procedures

- Chapter 10. The Organization of Customs Administration

- Chapter 11. Practical Measures to Promote Integrity in Customs Administrations

- Chapter 12. The Role of the Private Sector in Customs Administration

- Chapter 13. In Conclusion

- Boxes

- Bibliography

- Footnotes