eBook - ePub

World Economic Outlook, April 2003 : Growth and Institutions

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

World Economic Outlook, April 2003 : Growth and Institutions

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access World Economic Outlook, April 2003 : Growth and Institutions by International Monetary Fund. Research Dept. in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

2002eBook ISBN

9781589062122CHAPTER I ECONOMIC PROSPECTS AND POLICIES

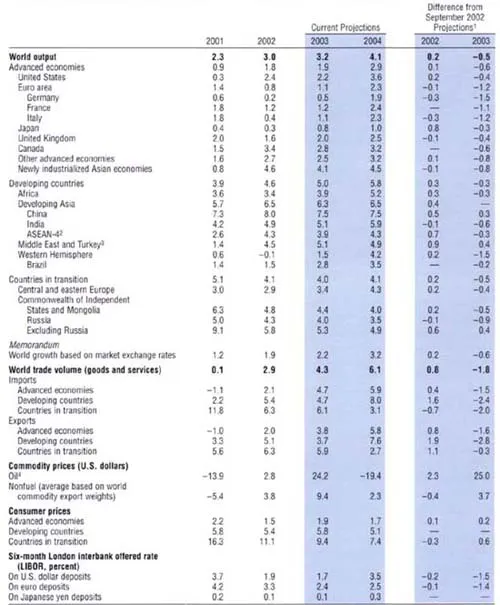

When the last World Economic Outlook was published in September 2002, the global recovery was expected to continue at a moderate pace, but the risks to the outlook were seen primarily on the downside. In the event, activity in the second and third quarters of 2002—except in western Europe—proved stronger than expected; correspondingly, global GDP growth for the year as a whole is now estimated at 3 percent, 0.2 percentage point higher than earlier projected (Figure 1.1 and Table 1.1). But since then the pace of the recovery has slowed, particularly in industrial countries, amid rising uncertainties in the run-up to war in Iraq and the continued adverse effects of the fallout from the bursting of the equity market bubble. Industrial production has stagnated in the major advanced countries, accompanied by a slowdown in global trade growth; labor market conditions remain soft; and forward-looking indicators—with a few exceptions—have generally weakened (Figure 1.2). And while global fixed investment has begun to turn up, it does not yet appear strong enough to sustain the recovery if consumption growth—a key support to demand so far in the upturn together with the turn in the inventory cycle—slows.

Figure 1.1. Global Indicators1

(Annual percent change unless otherwise noted)

The recovery is expected to remain moderate in 2003, with global growth returning to trend in 2004.

1Shaded areas indicate IMF staff projections. Aggregates are computed on the basis of purchasing-power-parity weights unless otherwise noted.

2Average growth rates for individual countries, aggregated using purchasing-power-parity weights; the aggregates shift over time in favor of faster growing countries, giving the line an upward trend.

3GDP-weighted average of the 10-year (or nearest maturity) government bond yields less inflation rates for the United States, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Canada. Excluding Italy prior to 1972.

4Simple average of spot prices of U.K. Brent, Dubai, and West Texas Intermediate crude oil.

Table 1.1. Overview of the World Economic Outlook Projections

(Annual percent change unless otherwise noted)

Note: Real effective exchange rates are assumed to remain constant at the levels prevailing during February 7–March 7, 2003.

1 Using updated purchasing-power-parity (PPP) weights, summarized in the Statistical Appendix, Table A.

2 Includes Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand.

3 Includes Malta.

4 Simple average of spot prices of U.K. Brent, Dubai, and West Texas Intermediate crude oil. The average price of oil in U.S. dollars a barrel was $25.00 in 2002; the assumed price is $31.00 in 2003, and $25.00 in 2004.

Figure 1.2. Current and Forward-Looking Indicators

(Percent change from previous quarter at annual rate unless otherwise noted)

The recovery in global industrial production and trade has slowed and most forward-looking indicators have turned down.

Sources: Business confidence for the United States, the National Association of Purchasing Managers; for the euro area, the European Commission; and for Japan, Bank of Japan. Consumer confidence for the United States, the Conference Board; for the euro area, the European Commission; and for Japan, Cabinet Office (Economic Planning Agency). All others, Haver Analytics.

1 Australia, Canada, Denmark, euro area, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

2Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Hong Kong SAR, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Taiwan Province of China, Thailand, Turkey, and Venezuela.

32002:Q1–Q4 data for China, India, and Russia are interpolated.

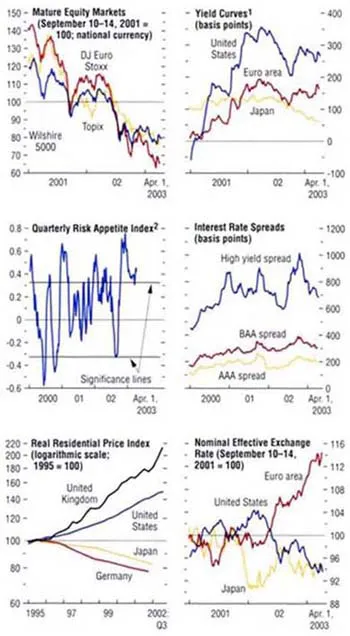

After strengthening in the last quarter of 2002, mature financial markets fell back in early 2003, with equity markets declining to 40–60 percent below their early 2000 peaks (Figure 1.3).1 This appears largely to have reflected rising risks and uncertainties, with respect to both the geopolitical situation and the sluggish pace of the recovery, offset in part by some improvement in risk appetite, At the same time, bond markets remained subdued, continuing to price in expectations of sluggish growth, while—perhaps aided by some easing of concerns about corporate governance—corporate spreads declined, particularly for high-yield paper. In foreign exchange markets, the depreciation of the U.S. dollar resumed in December, reflecting both geopolitical concerns and the continued heavy reliance of the United States on foreign capital inflows. By mid-March, the U.S. dollar had depreciated by 14 percent in trade-weighted terms from its early 2002 peak, accompanied by a 13 percent appreciation of the euro and a 4 percent appreciation of the yen. Since the middle of March, however, as expectations that the war would start shortly—and be over quickly—rose markedly, these trends have reversed, with global equity markets picking up, bond yields rising, and the U.S. dollar appreciating against most major currencies. At the time of writing, markets remain volatile, with the potential for substantial movements in either direction depending on how the geopolitical situation develops.

Figure 1.3. Developments in Mature Financial Markets

While risk appetite has picked up, equity markets remain weak, and the U.S. dollar has again begun to depreciate.

Sources: Bloomberg Financial Markets, LP; State Street Bank; Bank for International Settlements; and IMF staff estimates.

1 Calculated as the difference between the 10-year government bond rate and 3-month interest rate.

2IMF/State Street risk appetite indicators.

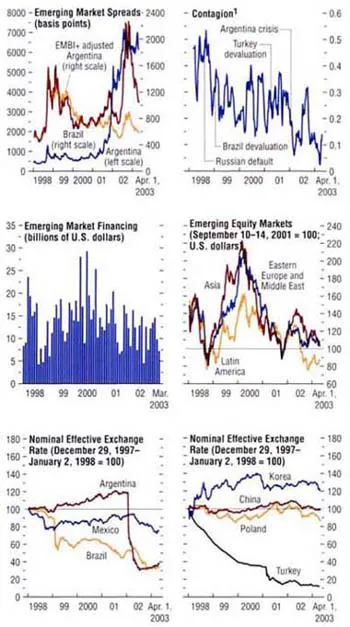

In emerging markets, financing conditions have improved, reflecting improved sentiment toward Brazil and—until recently—Turkey following the elections in those countries; the impact of actual and expected financial support from the international community, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF); and some improvement in risk appetite. During 2002, net capital flows picked up in all major regions except the Western Hemisphere—where foreign direct investment fell very sharply—although they still remain moderate by historical standards (Table 1.2). Emerging market spreads have declined markedly since October (Figure 1.4), although within this substantial tiering has emerged. In some key markets—including Russia, eastern Europe, and Mexico—spreads have declined sharply, in some cases to near historic lows. In contrast, where risks are still perceived to be significant, notably in some countries in South America and Turkey, spreads remain relatively high. A similar tiering is evident in primary markets, where—despite a marked pickup in issuance since November—only a few sub-investment-grade borrowers in Latin America have been able to access the market, and consequently most of them have been unable to prefinance their 2003 borrowing needs to any significant degree. Emerging equity markets have generally moved in tandem with mature equity markets; in currency markets, outside eastern Europe and South Africa, exchange rates have generally remained constant or fallen in trade-weighted terms (the latter primarily in some countries in Latin America and Asia—including China and Hong Kong SAR, whose currencies are closely linked to the U.S. dollar).

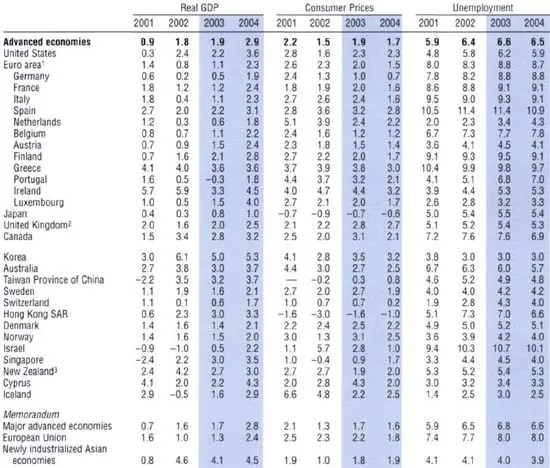

Table 1.2. Advanced Economies: Real GDP, Consumer Prices, and Unemployment

(Annual percent change and percent of labor force)

1 Based on Eurostat’s harmonized index of consumer prices.

2 Consumer prices are based on the retail price index excluding mortgage interest.

3 Consumer prices excluding interest rate components.

Figure 1.4. Emerging Market Financial Conditions

Emerging market financing conditions have improved in recent months, although spreads for some countries remain high, and primary market issuance is still modest.

Sources: Bloomberg Financial Markets, LP; J.P. Morgan Chase; and IMF staff estimates.

1Average of 30-day rolling cross-correlation of 20 emerging market debt spreads.

Geopolitical uncertainties have also had a significant impact on commodities markets. After exhibiting considerable volatility throughout much of 2002, oil prices rose sharply in late 2002 and early 2003, owing both to increased expectations of war in Iraq and to supply disruptions associated with the political crisis in Venezuela (see Appendix 1.1, “Commodity Markets”). Despite OPEC’s decision in early January to raise its output target by 1.5 million barrels a day, prices continued to climb, peaking in mid-March at $34 a barrel. Since that time, mirroring the developments in financial markets noted above, oil prices have fallen back sharply on expectations that the war would shortly begin and be over quickly, but the market remains exceptionally volatile. Nonfuel commodity prices also rose significantly during 2002, particularly for food, beverages, and agricultural raw materials, although they are still low by historical standards. While this partly reflected the global recovery, it was mostly due to adverse weather conditions in parts of North America, Australia, Brazil, and Africa; correspondingly, if conditions improve, nonfuel commodity prices are likely to increase only moderately further during 2003.2

Four features of the current conjuncture appear particularly germane to an assessment of the global outlook:

- Geopolitical and other uncertainties, and how they are resolved. In the run-up to the war in Iraq, geopolitical uncertainties increased sharply, reflected among other things in the rising trend (until very recently) in oil and gold prices. This is already having a substantial effect: notably, the upward revision in oil prices since the last World Economic Outlook and all the attendant uncertainties associated with it, accounts for a substantial proportion of the downward revision to global growth in 2003. Clearly, much now depends on the speed with which the conflict is resolved, the extent to which it is contained within Iraq, and the damage to infrastructural and other facilities, all of which are impossible to predict at this stage (see Appendix 1.2, “How Will the War in Iraq Affect the Global Economy?”). In contrast to the situation before the 1991 conflict in the Middle East, markets—especially since mid-March—appear to be pricing in a quick and relatively costless resolution of the situation. Correspondingly, the upside risks from a benign outcome, while real, may be smaller than the downside risks if matters turn out worse than expected.

- The continued “headwinds” from the bursting of the equity market bubble, and the extent to which these persist. In most countries, the direct impact of the past fall in equity markets on demand growth is likely to have peaked in late 2002 or the first half of 2003; thereafter, provided equity prices do not fall further, the drag on GDP growth—while still significant—should start to diminish. This is also broadly consistent with the historical experience, which suggests that GDP growth begins to fully recover two to three years after the bursting of an equity price bubble (see Chapter II). However, considerable uncertainties remain, not least with respect to the impact on the balance sheets of banks and insurance companies, in Japan and some countries in Europe. In corporate sectors, excess capacity, losses on defined benefit pension plans, and still-high corporate debt levels weigh on the investment outlook—to different degrees—in all three major currency areas (Chapter II).

- The marked differences in the macroeconomic stimulus in the pipeline in the key currency areas. In the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom, monetary and fiscal policies have been eased significantly more in response to the global slowdown than in the euro area and Japan (Figure 1.5), partly reflecting the smaller room for policy maneuver in the latter two. This pattern—reinforced by recent exchange rate movements—is expected to continue in 2003, and will tend to increase global dependence on U.S. growth.

- Movements in major currencies. As noted above, the U.S. dollar has depreciated markedly over the past year, a generally welcome development in light of the continued large imbalances in the global economy, discussed in more detail below. However, geopolitical uncertainties appear also to have played a significant role; correspondingly, currency markets are likely to remain volatile in the immediate future, with significant movements possible in both directions depending on how events unfold. Such movements have important effects on activity and inflation particularly when—as in Japan—the authorities have relatively little room for offsetting policy maneuver.3

Figure 1.5. Fiscal and Monetary Easing in the Major Advanced Countries

(Percent)

Monetary and fiscal policies have been eased significantly more in the United States and the United Kingdom than in the euro area and Japan.

...Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Content Page

- Assumptions and Conventions

- Preface

- Foreword

- Chapter 1. Economic Prospects and Policy Issues

- Chapter II. When Bubbles Burst

- Chapter III. Growth and Institutions

- Chapter IV. Unemployment and Labor Market Institutions: Why Reforms Pay Off?

- Annex: Summing Up by the Chairman

- Statistical Appendix

- Boxes

- World Economic Outlook and Staff Studies for the World Economic Outlook, Selected Topics

- Footnotes