- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reconstructing the World Economy

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reconstructing the World Economy by Il SaKong, and Olivier Blanchard in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

2010eBook ISBN

9781589069770SECTION IV. Global Imbalances: In Midstream

CHAPTER 8. Global Imbalances: In Midstream?

Before the crisis, there were strong arguments for reducing global imbalances. As a result of the crisis, there have been significant changes in saving and investment patterns across the world and imbalances have narrowed considerably. Does this mean that imbalances are a problem of the past? Hardly. This paper argues that there is an urgent need to implement policy changes to address the remaining domestic and international distortions that are a key cause of imbalances. Failure to do so could result in the world economy being stuck in “midstream,” threatening the sustainability of the recovery.

8.1. INTRODUCTION

Global imbalances are probably the most complex macroeconomic issue facing economists and policymakers. They reflect many factors, from saving to investment to portfolio decisions, in many countries. These cross-country differences in saving patterns, investment patterns, and portfolio choices are in part “good”—a natural reflection of differences in levels of development, demographic patterns, and other underlying economic fundamentals. But they are also in part “bad,” reflecting distortions, externalities, and risks, at the national and international levels. So it is not a surprise that the topic is highly controversial, and that observers disagree on the diagnosis and thus on the policies to be adopted.

Our purpose in this paper is twofold. First, we aim at clarifying the issues, laying down the facts, interpreting past and current imbalances, and forecasting their future evolution. Second, we argue that there are good reasons to want to reduce imbalances further. As a result of the crisis, there have been significant changes in saving and investment patterns across the world, and imbalances have narrowed considerably. This notwithstanding, we argue that there is an urgent need to implement policy changes to address the remaining domestic and international distortions that are a key cause of imbalances. Failure to do so could result in the world economy being stuck in midstream, threatening the sustainability of the world recovery.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 8.2, we review the arguments for or against reducing imbalances. Section 8.3 takes a brief look back at the evolution of imbalances before the crisis (with the Appendix presenting a more comprehensive discussion), and attempts to gauge the extent to which imbalances before the crisis reflected the problems and distortions discussed in Section 8.2. Section 8.4 discusses where the crisis has left us. Imbalances have decreased since the beginning of the crisis. The questions are (1) why this is, (2) whether these changes are permanent or transitory, and (3) how this affects the conclusions and policy recommendations reached before the crisis. We take up the last question in Section 8.5. We conclude that imbalances are likely to remain lower than they were before the crisis, but that the case for reducing some of them further is still very strong.

8.2. GLOBAL IMBALANCES: GOOD OR BAD?

Current account balances reflect a plethora of macroeconomic and financial mechanisms. And in a global world, there is no reason for current accounts to be balanced. Indeed, it is desirable for saving to go where it is most productive, and imbalances can therefore emerge naturally from differences in saving behavior, in the rate of return on capital, or in the degree of risk or liquidity of different assets. So, imbalances, even large ones, are surely not prima facie bad. It is therefore essential to be clear as to what factors are behind them, and then act, if justified, on the causes.

8.2.1. “Good” Imbalances

Consider three familiar examples of “good” imbalances. First, saving behavior: It makes good sense for countries whose population is aging faster than their trading partners’ to save and run current account surpluses in anticipation of the dissaving that will occur once the workforce shrinks and the number of retirees rises. Second, investment behavior: A country with attractive investment opportunities may well want to finance part of its investment through foreign saving, and thus run a current account deficit. Third, portfolio behavior: A country that has deeper and more liquid financial markets may well attract investors, generating currency appreciation and a current account deficit. In all these cases, it would be unwise to want to reduce imbalances: They reflect the optimal allocation of capital across time and space.2

But imbalances can be symptoms of underlying distortions, or be dangerous by themselves. Let us quickly go through the list.

8.2.2. Domestic Distortions

The list of potential examples here is also familiar: High private saving is not necessarily good. It may reflect a lack of social insurance, which forces people to engage in high precautionary saving. Or it may reflect poor firm governance, which allows firms to retain and reinvest most of their earnings. Conversely, low private saving can clearly be bad, driven by bubble-driven asset booms, or excessively rosy expectations about future growth. Public borrowing is often too high, reflecting political factors. And factors such as poor protection of property rights or lack of competition in the financial system can lead to excessively low investment. In all these cases, the purpose of policies should not be to reduce the resulting current account imbalances per se, but to reduce the underlying distortions. Doing so will typically reduce imbalances, but this is not the goal.

8.2.3. Systemic Distortions

Particularly following the Asian crisis, many emerging economies have run large current account surpluses and accumulated very substantial foreign exchange reserves. These reserves have been predominantly denominated in U.S. dollars, reflecting the role of the dollar in international transactions and the liquidity of the U.S. bond market.

One reason behind this strategy has been a reliance on export-led growth.3 Whereas this may be a reasonable growth strategy from the country’s perspective, and especially so if it starts from a position of excessively high external indebtedness, it comes at the expense of other countries. And the problem can become systemic if several countries representing a significant fraction of world trade adopt these strategies.

Another reason for the accumulation of reserves has been self-insurance.4 Whereas this may again be rational at the individual country level, it is globally inefficient relative to alternative arrangements, such as the establishment of credit lines, reserve-pooling arrangements, swap lines, or other forms of insurance.

To the extent that imbalances reflect such systemic distortions, the policy response should be to reduce these distortions at the systemic level. In the first case, the issue could in principle be addressed through some international mechanism to limit exchange rate undervaluation. In practice, however, designing and enforcing a mechanism that goes beyond international peer pressure is a daunting challenge. In the second case, the policy response should be to improve the global provision of liquidity and provide incentives for countries to decrease selfinsurance and reserve accumulation.

8.2.4. Domestic Risks

Even if the factors behind current account balances are “good,” they may interact with other distortions to create inefficient outcomes or increase risks.

For example, real appreciations driven by increases in capital flows can crowd out manufacturing activity and lead to Dutch disease-type phenomena—particularly in the presence of externalities that make changes in manufacturing activity very costly to reverse. Large current account deficits and real exchange rate appreciations resulting from credit booms fueled by “over-optimism” can be difficult to unwind without a protracted real depreciation, which can be very painful when the exchange rate is fixed and partner-country inflation is low.

Capital flows—particularly for smaller economies—may be volatile, leave in a hurry, and be disruptive. Capital flow volatility can be driven by selffulfilling factors, as well as by an underestimation of liquidity risk by borrowers. Having a large current account deficit has proven very costly in the current crisis—countries with larger initial deficits have experienced larger output declines.

In all these cases, underlying shocks are interacting either with distortions—for example, a tradable sector externality leading to Dutch disease—or with the underestimation of foreign exchange or liquidity risk by domestic borrowers. In principle, the right policy is thus to correct the externalities through taxes or subsidies, and limit the risks taken by domestic borrowers through prudential regulation or controls on capital flows.

8.2.5. Systemic Risks

In addition, if countries with external imbalances are large and capital flows liquid, imbalances may lead to systemic problems, namely the risk of “disruptive adjustments.” A case in point is the United States, where the risk that investor demand for U.S. assets would fall short of what was needed to finance a rapidly growing stock of external liabilities was often considered, before the crisis, to be one of the main risks facing the world economy (see for example IMF, 2005; Krugman, 2007; and Obstfeld and Rogoff, 2007).

Two remarks are relevant here. The focus in that discussion is often on net asset positions, and on the large reserve positions of central banks. As a matter of logic, what matters more may not be net, but rather gross external positions. Indeed, the cross-border effects of the financial crisis were initially transmitted through the large holdings of U.S. corporate securities by European banks, rather than through the “net” holdings of U.S. securities by emerging markets. And rapid changes in investor demand are probably less likely to occur when central banks rather than private investors are holding dollar assets.

In the presence of such systemic risks, the best policy response is not obvious. It may be that just taking care of the other distortions, for example limiting the foreign currency exposure of domestic borrowers, reduces the size of the problem or the disruptions from exchange rate adjustments, and makes the problem less important. Otherwise, intervention ex-post to allow for more orderly adjustment (for example in the form of extensive liquidity provision) may be the best response.

8.3. SO GOOD OR BAD? AN INTERPRETATION OF RECENT HISTORY

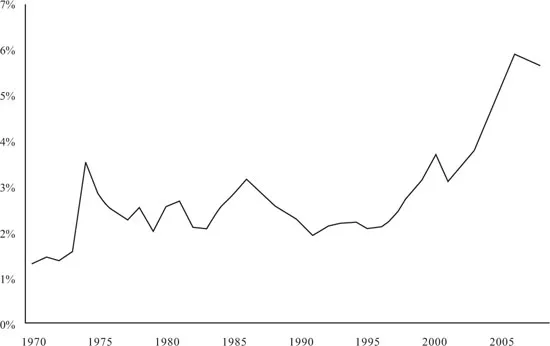

Figure 8.1 shows the absolute value of world current account balances scaled by world GDP and suggests a sustained increase in imbalances starting in 1996, with only a short dip at the time of the 2001–02 recession. We therefore start our analysis in 1996. The task of interpreting what happened during that period should in principle be straightforward: look at imbalances and identify distortions and risks. In practice, of course, the task turns out to be much harder, for two reasons.

Figure 8.1 Sum of absolute value of world current account balances

(ratio of world GDP).

First, the nature of imbalances has changed through time, with different factors and players playing an important role in different periods. A closer look at the evidence (see the Appendix) suggests dividing recent history into three main stages leading up to the cr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Section I Exit Strategies for Anti-Crisis Measures

- Section II Redesigning the Macro Framework

- Section III The Future Financial System

- Section IV Global Imbalances: In Midstream

- Section V Future of the International Monetary System

- Figures

- Footnotes