eBook - ePub

IMF Involvement in International Trade Policy Issues

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

IMF Involvement in International Trade Policy Issues

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access IMF Involvement in International Trade Policy Issues by International Monetary Fund. Independent Evaluation Office in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

2009eBook ISBN

97815890686745. The IMF’s mandate on trade policy issues is broad, but not precise.2 The root of the mandate lies in Article I(ii) which specifies that a purpose of the IMF is

…to facilitate the expansion and balanced growth of international trade, and to contribute thereby to the promotion and maintenance of high levels of employment and real income and to the development of the productive resources of all members as primary objectives of economic policy.

The generality of this statement has opened the door to controversy.

6. Within the IMF, a fairly broad interpretation of the purpose and responsibility of the IMF vis-à-vis international trade policy has evolved. Joseph Gold (Legal Counsel during 1946–79) held that, while the IMF has no regulatory authority over trade practices, its “soft” responsibility encompasses policies that encourage or ease the expansion of international trade. In surveillance, the IMF sees this responsibility as requiring attention to trade policies in both a passive mode (considering restrictive trade policies as an indication of the inappropriateness of a country’s exchange rate and a vulnerability to macroeconomic shocks) and an active mode (advising on trade policies that promote growth and stability). In lending, the IMF has interpreted the call in Article I(v) to “correct maladjustments in…balance of payments without resorting to measures destructive of national or international prosperity” as justifying conditionality on trade reform as well as a continuous performance criterion prohibiting new import restrictions for balance of payments purposes.

7. Some critics see this interpretation of the Articles as too broad. They contrast the IMF’s concrete purposes to promote exchange rate stability, oversee the multilateral payments system, and provide temporary balance of payments support with the vague reference to promoting international prosperity. They tend to see a role for the IMF in advising or agreeing on conditionality on trade policies only where immediate balance of payments issues are at stake. They reject the notion that the general language in the Articles gives the IMF free rein to involve itself in, and especially establish conditionality on, policies as far afield from the IMF’s core expertise as trade policy.

8. With due respect for this debate, the evaluation focuses on the IMF’s record of involvement in trade policy, not the legal legitimacy of its involvement. In the IEO’s view, the sections of the Articles that are interpreted as giving the IMF responsibilities on trade policies to fulfill its purpose of facilitating international trade do not provide precise direction. But, they are general enough to underpin a wide spectrum of engagement.

9. Interinstitutional cooperation is essential for the IMF to be effective on trade policy issues. Two aspects of the institutional landscape reinforce this point. First, since the IMF has few resources to devote to trade policy, it must look to organizations such as the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), even for the tools needed to address macroeconomic effects of trade policy. Second, the international community established the WTO as the locus of multilateral trade cooperation. The WTO, however, is primarily a negotiating forum, with limited capacity for taking views on how trade policies affect global, regional, or national macroeconomic vulnerabilities. Providing such views must fall to the IMF, which in turn must maintain coherence with the WTO’s framework.

10. Some indicators point to difficulties in inter-institutional cooperation on trade policy. For IMF staff as a whole, the exception is cooperation with the World Bank. Especially in UFR work, 70–80 percent of staff that responded to an IEO survey had frequent or occasional contact with World Bank staff on trade issues. But the case studies of UFR (where most Fund-Bank cooperation on trade policy occurs) found high variance in the effectiveness of interaction—similar to that found in an earlier IEO evaluation of structural conditionality. Interaction with other institutions—the OECD (which is active on advanced country trade policy), the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), and regional development banks—was low. Vis-à-vis the WTO, over 60 percent of staff surveyed reported negligible contact. Most either had never read or were unsure if they had read a WTO trade policy review (TPR) on their country.

11. But a deeper look at the IMF’s links with the WTO—the focus of the rest of this section—suggests stronger cooperation than the survey indicates.3 Most contacts were channeled through small groups in the Fund’s Policy Development and Review Department (PDR), the (now closed) Geneva Office, FAD, a (now dissolved) trade division in the Research Department (RES), and the Legal Department. Management contacts were cordial, often close, and generally productive. Several IMF research papers prepared during 2002–04 at the request of the WTO Secretariat (on topics including preference erosion, trade effects of exchange rate variability, and revenue effects of trade liberalization) were warmly received.

12. Reasonably comprehensive agreements underpin IMF-WTO cooperation. The 1996 Cooperation Agreement formalizes procedures for document exchange and representation, observership, and written submissions of each institution in the other’s decision-making bodies. It also specifies conditions in which informal staff contact should occur. A 1998 Coherence Report addresses joint issues in “structural, macroeconomic, trade, financial and development aspects of economic policy making,” but follow-up has been less structured. Meetings of the working group for the report, comprising senior staff from the IMF, World Bank, and WTO, petered out after 2001. IMF management did not support a staff effort in 2003 to revive them. After 2004, the Executive Board Committee on Liaison with the WTO was also inactive. Informal channels of communication have kept coherence alive, though with less ambition than initially envisaged.

13. Would formal contacts have produced better outcomes? Several issues identified in the 1998 Coherence Report as needing common approaches (such as resolving tensions between WTO reciprocal trade negotiations and IMF emphasis on unilateral liberalization, helping interested countries prepare for WTO accession, and dealing with PTAs) are ones that this evaluation raises as weaknesses in the IMF’s work. Formal contacts might have helped focus the IMF on them.

14. Even though few overt problems arose, relations between the IMF and WTO were not trouble-free. Two aspects of the relationship have created actual or potential difficulties. First, while both institutions are dedicated to a common vision of a liberal global trading system, their approaches to trade liberalization are fundamentally different. Second, some actual and potential tensions arise from overlaps in jurisdictions and responsibilities.

15. Tensions over differing approaches to liberalization raise important issues but have for now been dissipated by a drop in the IMF’s use of trade conditionality. The WTO’s approach involves reciprocal liberalization through multilateral negotiations backed by a dispute settlement mechanism. The IMF aims to support best practices—trade policies (even if not the result of reciprocal bargaining) it views as bolstering efficiency and stability. Also, the WTO provides greater leeway for its developing country members to phase in global agreements, while the IMF aims to apply economic principles uniformly across its members, albeit with muscle linked to whether a country has a lending arrangement. Tensions between the two approaches were evident in some countrie’s complaints that unilateral trade reforms embedded in IMF-supported programs without reciprocal concessions from trade partners or credit in future negotiations weakened their bargaining power in WTO negotiations. IMF staff pointed out that conditionality related to applied tariffs whereas WTO agreements relate to bound tariffs, and, anyway, considerations of economic efficiency drove conditionality. With the IMF retreat from trade conditionality in recent years, the issue has become moot.

16. Tensions from differing approaches of the two institutions to the use of import restrictions for balance of payments reasons have also receded. Countries using their rights under WTO rules to apply import restrictions to safeguard their financial position or ensure an adequate level of reserves are subject to review by the WTO’s Committee on Balance of Payments Restrictions (CBR). The IMF is tasked with providing a statement to the CBR on the country’s current and prospective balance of payments situation. In practice, most IMF statements went beyond this role, calling for early removal of the restriction as other methods of adjustment were preferable. The CBR agreed with the IMF’s view in only about half the cases. One case (India, 1997), however, resulted in the United States filing a complaint with the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) that brought to the fore tensions over how the IMF determines reserve adequacy and its role in the CBR. These tensions were not resolved but became dormant as no new cases came to the CBR during 2001–08.4

17. Actual or potential tensions arising from different ways the institutions view their jurisdictional boundaries are a greater concern. Inconsistency (which existed even during the GATT) in how the two institutions distinguish exchange and trade restrictions creates scope for jurisdictional conflicts. One indeed occurred in China’s accession to the WTO (Box 2)Box 2, Background Document 2). Even more thorny is the potential for different interpretations of the two institutions’ roles in exchange rate policies. GATT Article XV provides that the IMF’s determination on whether a country’s exchange rate policy is consistent with the Articles of Agreement is binding. But observers note that the DSB, being independent, may not feel bound by the IMF’s assessment. It is beyond the scope of this evaluation to judge the potential for conflict on this issue.

18. The low-key cooperation between the two institutions in other specialized areas seems appropriate. IMF staff participate in the Integrated Framework (a process for identifying needs for and coordinating trade-related TA) mainly by providing input on macroeconomic policies and projections. IMF participation in Aid for Trade (a WTO initiative to coordinate trade facilitation TA) has also been narrow. The Trade Integration Mechanism (TIM)—the IMF’s response to pressure from developing countries for financial assistance to offset losses from trade preference erosion—was warmly endorsed by many of the evaluation team’s interlocutors at the WTO, though only three countries have used the scheme since its inception in 2004.

19. The WTO Secretariat is concerned about the IMF’s diminishing engagement in trade policy issues. The Secretariat views IMF conditionality on unilateral liberalization as inappropriate. But it sees an engaged IMF, assessing and publicizing the macro effects of trade policy, as crucial to the effectiveness of efforts to maintain and strengthen an open global trade system. This view reflects the Secretariat’s own limited capacity for analysis, its focus on micro rather than macro aspects of trade policy, and the fact that the IMF, through surveillance and its position among global institutions, has interlocutors (finance ministries and central banks) that influence economic policies but have no direct role in WTO fora (trade negotiations and trade committees). Thus, the Secretariat at all levels regretted the recent scaling back of the IMF’s capacity for work on trade policy (closure of the Geneva Office, merger of PDR’s Trade Policy Division with two other divisions, and elimination of RES’s trade division). They cautioned that in a “business-as-usual” world, these steps would probably not impair the global trade environment, but in a “not-business-as-usual” world—a clear risk at present—the implications could be serious.

20. Executive Board guidance on trade policy since the mid-1990s pushed staff both to broaden the range of issues they covered and to be more selective.5 Discussing the 1994 Comprehensive Trade Paper (an IMF staff review of trade policy issues that was conducted every few years until 1994), Directors asked for more analysis of several issues: macroeconomic effects of trade policies; spillovers, especially from PTAs; and effects of the Uruguay Round, especially on net food importers and countries facing preference erosion. In later years, the Board also asked for staff attention to countries’ positions in the Doha Round, market access for developing country exports, and trade in services. But staff interviewed for the evaluation saw the Board’s decision to abandon the Comprehensive Trade Paper as a sign of reduced interest in trade issues. This perception was reinforced by the streamlining of structural conditionality in 2000 and of trade policy surveillance in 2002. Also, as criteria for streamlining trade advice emerged only gradually through 2005, staff were often unclear when to address issues.

21. Even allowing that mixed signals were inevitable in the changing global trade environment, Board guidance to staff was vague. What many staff members described to the evaluation team as “cyclicality” in the Board’s interests made staff wary in addressing trade policy issues. Also, while the IMF’s objectives for traditional trade barriers were clear, for new trade policies—especially PTAs and trade in financial services—they were not. For both, the Board asked for IMF engagement (though for trade in financial services this request was not made explicitly until 2002) but left loose ends as to when, against what criteria, and with what objectives. Vis-à-vis PTAs, this may have reflected concerns that staff were too exacting in pushing high standards for minimizing possible distortions from PTAs. Thus, an effort to define an institutional perspective on key PTA issues in a 2006 Board seminar met with limited success, and the staff paper for that seminar was not released to the public.

22. PDR’s Trade Policy Division made a reasonable effort to filter what it saw as Board guidance to operational staff. In its comments on mission briefs and staff reports, the division rather systematically pressed missions to cover trade policies in countries with the most restrictive stances.6 For advanced countries, where tariff and nontariff barriers tended to be low, PDR pressed for strong positions on issues such as subsidies and countervailing duties. Often a Trade Policy Division staff member participated on surveillance missions. Even after the Comprehensive Trade Paper was abandoned, PDR put several thoughtful papers on IMF work on trade policy to the Board. Management interest in trade policy was more cyclical, peaking across the spectrum of issues during 2001–03, when the Managing Director and First Deputy Managing Director were strongly committed to an active IMF role in trade issues. Recently, management has taken less interest, at times discouraging staff from covering trade policy issues in developing and advanced countries.

A. Trade Policy Issues in UFR Work

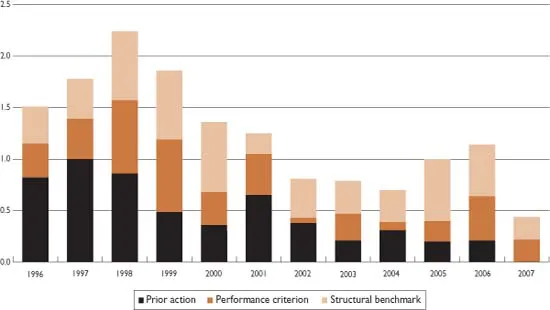

24. Despite a wave of trade liberalization in the late 1980s and early 1990s, trade liberalization still occupied a central spot in IMF-supported programs through 2000. This reflected partially the fact that some countries (especially certain previously centrally planned economies) had not been part of the liberalizing trend, but also the facts that some countries had pursued a measured pace of liberalization and others had stalled in their liberalization. Most countries using IMF resources had some trade reform agenda in place, and conditionality aimed to prevent derailments or quicken the pace of change. In 1996, arrangements (Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility (ESAF), Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF), Stand-By, and Extended) had, on average, one-and-a-half conditions (prior action, performance criterion or structural benchmark, excluding the standard continuous performance criterion prohibiting new import restrictions) on trade policy in the initial program (Figure 1). More than half of these conditions pertained to traditional trade policies and more than a third to customs administration, often supported by TA from FAD, which averaged some 20 trade-related TA reports per year during the evaluation period.

Figure 1. Average Number of Trade Policy Conditions per Arrangement, 1996–2007

(As agreed in the initial program, excluding continuous performance criteria prohibiting new import restrictions)

Sources: IMF reports and IEO calculations.

Box 3. The IMF’s Approach to Trade Protectionism

Underlying IMF advice on trade policy is rather widely accepted economic analysis. This concerns basic arguments for and against protection of domestic economic activity from foreign competition. Some reasons for protection—to “keep the money at home” or “level the playing field” are unsound. Others with some validity are to favor sectors considered important for national welfare (e.g., agriculture); to develop an infant industry; to improve short-run balance of payments positions; to raise fiscal revenue; or to improve the terms of trade (the optimum tariff argument).

These justifications, however, typically reflect second-best approaches to market failures that are often unrelated to trade. Thus, infant industry protection might look attractive when potentially competitive industries cannot attract private capital, perhaps because capital markets are undeveloped, social benefits are not internalized by the private sector, or external economies of scale exist. In such circumstances, the IMF’s approach—supported by economic analysis—is that the market failure should be corrected by policy that directly targets the source of the problem (the first-best solution). For example, if domestic production is suboptimal, supply...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Content Page

- Foreword

- Abbreviations

- Executive Summary

- 1 Introduction

- 2 What Is the Nature of the IMF’s Mandate to Cover Trade Policy?

- 3 Institutional Architecture for Trade Policy: How Well Has Cooperation Worked?

- 4 The IMF’s Evolving Role in Trade Policy: How Was the Process Guided?

- 5 IMF Advice on Trade Policy: How Well Was the Approach Carried Out?

- 6 How Effective Was the IMF’s Work on Trade Policy Issues?

- 7 Findings and Recommendations

- Annexes

- Background Documents

- Statement By The Managing Director, Staff Response, and The Acting Chair’s Summing Up

- Footnotes