UN Millennium Development Library: Who's Got the Power

Transforming Health Systems for Women and Children

UN Millennium Project

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

UN Millennium Development Library: Who's Got the Power

Transforming Health Systems for Women and Children

UN Millennium Project

About This Book

The Millennium Development Goals, adopted at the UN Millennium Summit in 2000, are the world's targets for dramatically reducing extreme poverty in its many dimensions by 2015 income poverty, hunger, disease, exclusion, lack of infrastructure and shelter while promoting gender equality, education, health and environmental sustainability. These bold goals can be met in all parts of the world if nations follow through on their commitments to work together to meet them. Achieving the Millennium Development Goals offers the prospect of a more secure, just, and prosperous world for all.

The UN Millennium Project was commissioned by United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan to develop a practical plan of action to meet the Millennium Development Goals. As an independent advisory body directed by Professor Jeffrey D. Sachs, the UN Millennium Project submitted its recommendations to the UN Secretary General in January 2005. The core of the UN Millennium Project's work has been carried out by 10 thematic Task Forces comprising more than 250 experts from around the world, including scientists, development practitioners, parliamentarians, policymakers, and representatives from civil society, UN agencies, the World Bank, the IMF, and the private sector.

This report lays out the recommendations of the UN Millennium Project Task Force on Child and Maternal Health. The Task Force recommends the rapid and equitable scale-up of interventions like the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness, the universal provision of emergency obstetric care, and sexual and reproductive health services and rights be provided through strengthened health systems. This will require that health systems be seen as social institutions to which all members of society have a fundamental right. This bold yet practical approach will enable every country to reduce the under-five mortality rate by two-thirds and the maternal mortality rate by three-quarters by 2015.

Frequently asked questions

Health status and key interventions

Connecting maternal health and child health

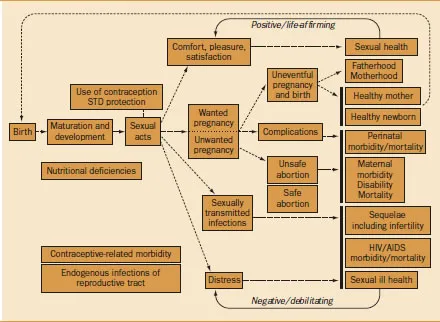

Figure 3.1 Conceptual map of sexual and reproductive health |  |

| Women's agency is positively correlated with women's health and children's health | Such social and institutional arrangements influence the way events depicted in the map are experienced, because these arrangements function as the repositories of power and resources that individuals draw on to protect their health and prevent or treat disease (Link and Phelan 1995). These resources include not simply economic resources but also such nonmonetary assets as social networks, prestige, education, information, and legal claims. For example, a woman who, because of access to resources such as education, legal claims to gender equality, and strong social networks, has been able to obtain formal employment and achieve financial independence is likely to have greater power to negotiate the conditions of intimate relationships, including use of contraception, and to have the resources to obtain the contraceptive that best meets her needs. The constellation of power and resources—the assets— that this woman accesses through multiple social and institutional arrangements thus influences her experience of the box in figure 3.1 labeled “use of contraception/STD protection” and the subsequent sexual and reproductive health stages in the map (sexual acts, wanted/unwanted pregnancy, comfort/ pleasure/satisfaction, and so on). |

| These assets are not evenly distributed in any society. Gender, class, race, and ethnicity are intersecting social hierarchies that often act as a grid of inequality through which an individual's experience of the social and institutional arrangements is filtered. Imagined this way, the map helps conceptualize the mechanisms by which inequality in access to power and resources ultimately affects health. |

Child health

| In parts of the world, progress in reducing child mortality has stalled | Important gains were made in child survival during the second half of the twentieth century (Freedman and others 2003). Globally, the under-five mortality rate (the number of deaths per 1, 000 live births per year) declined from 159.3 in 1955–59 to 70.4 in 1995–99 (Ahmad, Lopez, and Inoue 2000). The decline was most rapid during the 1970s and 1980s. Although the rate of decline slowed during the 1990s, child mortality still fell about 15 percent during that decade. This was an impressive achievement given the events that affected international public health development programs toward the end of the twentieth century— economic stagnation, increasing political instability and conflict, growing resistance to antimalarial drugs, and the relentless spread of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, to name a few. Overall the number of children under the age of five who die in the world each year fell from about 13 million in 1980 to an estimated 10.8 million by the end of the century (Black, Morris, and Bryce 2003). |

- A small number of diseases and underlying biological factors are responsible for the large majority of childhood deaths.

- The Goal for reducing child mortality cannot be met without a major effort to reduce newborn deaths—those that occur during the first four weeks of life.

- Existing interventions, if implemented through efficient and effective strategies (in a way that reaches those who need to be reached), could prevent a substantial proportion of existing mortality.

- Child mortality is distributed in an extremely uneven manner. Not only between regions and countries but also within countries, socioeconomic inequities, to a large degree, determine which children live and which ones die.

- Existing interventions can be implemented most effectively in countries where health systems work best.

- Child health programs in developing countries are grossly underfunded; major new investments will be needed in order to achieve the Goal.

Geographical distribution and causes of death

| A few diseases are responsible for the majority of childhood deaths | Some 10.8 million children are estimated to die before the age of five every year (Black, Morris, and Bryce 2003). Forty-one percent of these deaths occur in Sub-Saharan Africa, and 34 percent occur in South Asia. Just six countries account for half of all childhood deaths (table 3.1), and 90 percent of deaths occur in 42 countries. |

| Five diseases—diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, measles, and AIDS—are responsible for an estimated 56 percent of deaths in children under five (table 3.2). In addition, about one-third of all deaths occur during the first month of life and have conventionally been grouped together as “neonatal deaths.” These have been attributed to a small number of biological conditions: complications of prematurity (27 percent), sepsis and pneumonia (26 percent), birth asphyxia (23 percent), and tetanus (7 percent) (Lawn and others 2005). These neonatal deaths have been relatively neglected in programs aimed at reducing child mortality and, for this reason, they are a special focus of this report. |

| Deaths from injuries are becoming proportionally more important | The imp... |