![]()

1 Introduction*

The economic, cultural, and political life of America has been often shaped by immigration. This was never more the case than in the colonial and early national periods. To comprehend the evolution of American society, the immigrant experience must be understood. Who immigrated and why, what were their social origins and characteristics, what resources did they bring with them, what was their journey like, how did they finance that journey, and how did they fit into established American society? These questions guide the investigation that follows. In particular, this book focuses on the migration experience of the Germans, the largest non-English-speaking European migration to English America during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

The integration of foreign speakers into American society has frequently caused public concern and affected American immigration policy. Germans were the first major wave of European foreign speakers entering English America. Their migration experience offers historical perspective on how Americans dealt with such immigrants and how such immigrants coped with their entry into American society. Subsequent waves of foreign speakers entering English America have continued to the present day. Understanding the past may help us better comprehend the present and deal with the future.

Immigrants molded early America. Their nature and the nature of the institutions they brought with them, when filtered by the constraints of their new American environment, formed the basis of American culture, economy, and political values (Fischer 1989; Roeber 1993). The character and social origins of early European-Americans, however, have been often disputed.1 Their occupational and family composition, levels of education, proportion who came as bonded servants, among other characteristics, have yet to be conclusively established.

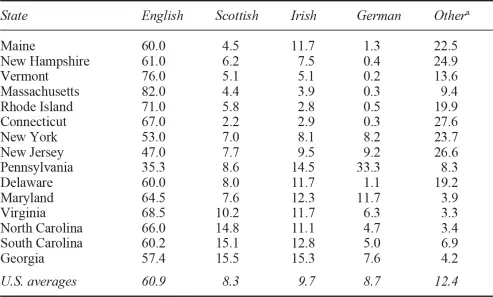

America as a melting pot of nations began in the colonial period. While traces of many nationalities can be found, the dominant group among European-Americans of non-English-speaking ancestry were the Germans. Table 1.1 presents the percentage distribution of the white population of the United States by ethnicity and state from the 1790 census—the first U.S. Federal census. While the accuracy of the ethnic designators in this census has been disputed, the general magnitudes and their relative patterns are still informative.2 Nothing as comprehensive exists for the colonial period.

Table 1.1 Percentage distribution of the white population of the United States by nationality and state from the 1790 census (%)

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census (1975: 1168).

Note

a This category is composed of Dutch, French, Swedes, Swiss, and non-assignable individuals. The non-assignable group dominates this category in all states except New York, New Jersey, and Delaware, where the Dutch comprise the majority of this category.

White Americans of English ancestry were the majority in every state except New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Those of German ancestry were a third of the population of Pennsylvania—almost equal to the English percentage, and approximately 10 percent of the population in the neighboring states of New York, New Jersey, and Maryland. If Dutch, Swiss, and Swedes are included in the German category, this group would likely be the largest single ethnic group in Pennsylvania and the second largest in New York, New Jersey, and Maryland. Elsewhere, the percentage of white Americans of German ancestry lagged well behind those of English, Scottish, and Irish ancestry.

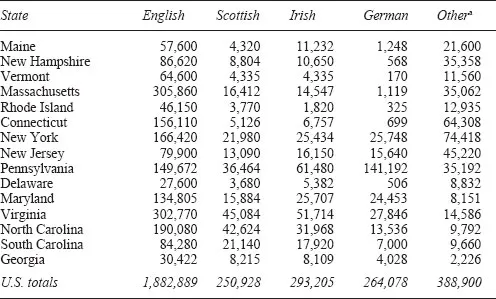

Table 1.2 transforms the approximate ethnic percentages from the 1790 census into their raw population totals. Just over half of German-Americans were concentrated in Pennsylvania. Another 25 percent were in the neighboring states of New York, New Jersey, and Maryland. The rest were scattered across the southern states. Again, if the Dutch, Swiss, and Swedes are included in the German category, the concentration of Americans of Germanic ancestry in the middle states would be higher. The middle states from New York through Maryland, principally Pennsylvania, were overwhelmingly the location of German- Americans by the end of the eighteenth century.

Table 1.2 The raw distribution of the white population of the United States by nationality and state from the 1790 census

Source: Derived from the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1975: 25–36, 1168).

Note

a This category is composed of Dutch, French, Swedes, Swiss, and non-assignable individuals. The non-assignable group dominates this category in all states except New York, New Jersey, and Delaware where the Dutch comprise the majority of this category.

This concentration of German-Americans in the middle states was the direct outcome of prior immigration. Table 1.3 estimates the contribution of German immigrants to the population growth of the middle colonies of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware.3 This contribution was substantial, peaking at 30 percent during the decade of the 1750s. Considering that German immigrants were more family oriented than British and Irish immigrants, the indirect contribution of German immigration through American-born offspring to subsequent population growth was also higher than for other ethnic groups (Chapters 5 and 9).

Table 1.3 Estimated population growth in the Delaware valley colonies, 1730–75

| Decade | Population increase in Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania | Estimated German immigration per decade as a percentage of population growth |

1730–40 | 58,493 | 20.74 |

1740–50 | 62,883 | 27.15 |

1750–60 | 91,003 | 30.42 |

1760–70 | 82,218 | 8.82 |

| 1770–75 | 59,666 | 7.89 |

Sources: Derived from U.S. Bureau of the Census (1975: 1168); Wokeck (1981: 260–1); chapter 2, figure 2.1.

Notes

The increase from 1770–80 was divided in half to derive the 1770–5 estimate. This was necessary because German immigration stopped at the America revolution in 1775.

The impact of German immigration on the population of Pennsylvania was noted at the time. For example, in 1728 Governor Thomas estimated that Germans constituted three-fifths of the population (Jacobs 1897: 148). By 1760, Pennsylvanians of German heritage were estimated to still be in the majority (Diffenderffer 1899: 97–106). By 1790, they were still the dominant ethnic group in Pennsylvania, though no longer a majority of the population (Table 1.1; footnote 2).

Both the long-run trend and the short-run fluctuation in the region’s economic activities were linked to the ebb and flow of German immigration (Nash 1979: 161–97, 233–63; Smith 1981). For example, the variance in acreage warranted (brought under cultivation) in Pennsylvania during the eighteenth century closely matches the variance in German immigration through the port of Philadelphia (Lemon 1972: 68; Chapter 2, Figure 2.1). The regional labor market was dependent on the continued arrival of German immigrants to provide a fresh source of hired labor. German immigration was an essential part of the cultural and economic development of this region during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Sustained efforts to recruit German immigrants to British North America began with the founding of Pennsylvania by William Penn in 1682. Penn himself was half Dutch and had made several apostolic journeys to the Rhineland prior to receiving his colonial grant in 1682. He naturally turned to Germans to help populate his new colony. He established agents in Holland, the most important being Benjamin Furly, who spread enticing accounts of the new colony, some written by Penn himself. Penn also sold Pennsylvania lands to merchants in Krefeld and Frankfort to help recruit German colonists. While some German colonists went, their numbers were small, under 200, compared with what would follow in the eighteenth century. These early immigrants, however, provided favorable accounts, which influenced Germans in later years to choose Pennsylvania as their favored New World destination.4

German emigration to British North America began in earnest in 1709 when approximately 14,000 desperately poor Rhinelanders, escaping starvation and the ravages of the War of the Spanish Succession, fled to Holland and then to England. They petitioned the British government for relief and assistance. With this assistance some 3,800 were transported to Ireland, 3,200 to the colony of New York, 650 to the Carolina colonies, and some 2,000 returned to Germany. The rest, those who had not perished during the ordeal, made their home in England.5

While Pennsylvania was not a serious contender for this initial wave of German immigrants to English America, it became the ultimate beneficiary. The Germans who arrived in New York experienced hard times and ill treatment, which prompted many to move overland to Pennsylvania. The letters they sent back to Germany diverted German emigrants bound for the New World to Pennsylvania thereafter. The Swedish botanist and traveler, Peter Kalm, while visiting the colonies in 1748, recounted these events in his journal:

The Germans not satisfied with being themselves removed from New York, wrote to their relations and friends and advised them if ever they intended to come to America not to go to New York, where the government had shown itself so inequitable. This advice had such influence that the Germans, who afterwards emigrated in great numbers to North America, constantly avoided New York and kept going to Pennsylvania.

(Kalm 1937: vol. 1, 142–3)

After 1709, German immigration to the Delaware valley increased. Many Germans who ultimately made their homes in Maryland, New Jersey, Virginia, and Delaware landed initially in Pennsylvania. Philadelphia became the primary port of entry and remained so throughout the eighteenth and into the early nineteenth century (Chapter 2). As such, the surviving records from the port of Philadelphia, and from Pennsylvania’s colonial and commonwealth governments, form the evidential basis for studies of German immigration to America. Concentrating on Pennsylvania captures both the dominant and representative experience of Germans immigrating to America in this period.

The proliferation of Germans in Pennsylvania alarmed the English inhabitants and attracted the attention of the provincial council and the governor. Addressing the provincial council in 1717, Governor William Keith, stated,

that great numbers of foreigners, from Germany, strangers to our language and Constitutions, having lately been imported into this Province, daily dispersed themselves immediately after Landing, without producing any Certificates, from whence they came or what they were; & as they seemed to have first Landed in Britain, & afterwards to have left it without any License from the Government, or so much as their knowledge, so in the same manner they behave here, without making the least application to himself or to any of the Magistrates; That as this Practice might be of very dangerous Consequences, since by the same method any number of foreigners from any nation whatever, as well Enemys as friends, might throw themselves upon us; The Governor, therefore, thought it requisite that this matter should be considered . ...