- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First Published in 1970. This volume is part of the Social History of Science series, reprinted with an new index. The essay focuses on the history and management of literary, scientific and mechanics' institutions with a special interest in how far these institutions might be developed and combined as to promote the moral well-being and industry of the country.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Essay on History and Management by James Hole in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

MECHANICS’ INSTITUES.

CHAPTER I.

HISTORY.

THE year 1851 will ever be memorable as the epoch of the Great Exhibition. We then witnessed, collected into one focus, the best results of the skill, taste, and industry of the world. Different nations, no longer rivalling each other in military contests or diplomatic chicane, tried whether peace could not show more glorious victories than war! Each learnt by comparison its peculiar merits or special deficiencies, and every member of that Congress of Nations was benefited by the lesson.

Of the many consequences flowing from this grand organisation of the products of industry, we note the steady rise of a feeling for the industrial education of the people in the minds of those whose interest in the Exhibition was not confined to the temporary amusement of a few hours. If so much had been done without any special culture on the part of the people, how much more might be done with it? If we beheld the labours of our superior workmen only, developed by the energy of the capitalists, what might be anticipated when all our people should have received the benefits of instruction? Moreover, with such wonders of skill and ingenuity before us, applied to everything that could minister to human need, surely the knowledge that enabled us to achieve all this was of some importance, and ought to meet with befitting treatment at our hands. As mere knowledge, it was as dignified as the lore taught in our Colleges and Universities, and in its direct influence on human happiness the two could not for one moment be compared.

With a surplus in hand of 150,000l., for which, amidst many claimants, there were none whose proposals would have satisfied the nation, it was wisely determined to provide “a common centre of action for the dissemination of a knowledge of science and art among all classes,” to increase the means of industrial education, and extend the influence of science and art upon productive industry; and although the surplus was to be applied in “furtherance of one large institution, devoted to the purpose of instruction, adequate for the extended wants of industry,” yet it is to be “in connexion with similar institutions in the provinces.”

The Commissioners, we think, acted wisely in preferring to secure one comprehensive Institute in London, rather than distributing the fund in driblets among local Institutes, where the result would have been comparatively small, or at least less visible or encouraging. It would be a great mistake, however, to imagine that the erection of one temple to art, science, and industrial education in the metropolis, however magnificent as a whole, and however complete in all its details, will satisfy the wants of the country. London is not Great Britain; and though the centre of the largest population, it is not the chief centre of those industries which make Great Britain the workshop of the world. Manchester and its surrounding towns, Stockport, Bolton, Preston and Blackburn, Birmingham, the Potteries, Nottingham, Leicester, Leeds and Newcastle, Bradford, Sheffield, Huddersfield, and Halifax; — one has but to name these densely-populated centres of the productive power of the nation, to see that any scheme for the diffusion of the arts and sciences whose operation should be confined to London, would fail in its most important function. Indeed, all the requisitions to the Commissioners from the provincial towns insist upon local establishments in connexion with the Metropolitan Institute, as a part of the scheme.1

Neglect of the interests of science and art in this country on the part of the nation, is a complaint so often repeated as to be almost stale. Much has been done by individuals and voluntary associations, but done without system and without relation to actual wants, so that a large amount of effort has been unproductive. An unreasonable jealousy of all interference of Government on the part of the people, and an almost utter indifference on the part of the Government itself to its own highest duties, have in past years prevailed. The intense worship of wealth and rank compared with that paid to intellect, and the struggle of parties and factions on great political questions, have also contributed to this neglect. While other countries have been moving unostentatiously onward in the path of education, both for youths and adults, and have, without a tithe of our natural advantages, become able to tread closely on our heels in the march of civilisation, this nation has been indulging its characteristic self-complacency, and looking with supremest contempt on “those foreigners.” With frigid indifference we have seen growing up amid our refined and luxurious civilisation, the densest, brutalest ignorance, — side by side with our enormous wealth, an incredible amount of human misery, — the palaces of the rich elbowed by the nests of fever and the hovels of despairing wretchedness. While we have been squabbling about who shall teach the children, and what they shall be taught, hundreds of thousands have grown up untaught in all save vice. And now that the Great Exhibition is over, we learn that even the shop is in danger, — a fact, we may hope, that will leave its due impression. More remarkable than even these contrasts is the noise we make when we are about to extend some small help to education. “Speech from the throne,” “Strong feeling in the country,” “Decided expression of the House,” “Editorial thunder in all newspapers,”—and all for a few thousands; while a million or two more or less, in Army or Navy estimates, would not have created a tithe of the excitement. And yet what item is there in the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s budget which can rank for one moment with that devoted to advance the intelligence of the country? What “interests,” West Indian, Cotton, Shipping, or any other, can be compared with the “Working-Class Interest,” and what duties of more moment than attention to the moral and social advancement of our swarming population?

What part government should take in promoting adult instruction, is a question of expediency and of public opinion. It must, like all questions of government interference, be decided upon its own merits; and we shall offer in the course of this paper some remarks bearing upon it. The country is indebted to the Society of Arts for mooting the question, How are Scientific, Literary, and Mechanics’ Institutes to be improved? For this opens up the whole question of adult instruction. In promoting the Great Exhibition, the Society of Arts rendered the state some service; to their lectures we are probably indebted for the magnificent scheme proposed by the Royal Commissioners. But the Society of Arts will confer a boon on the country greater than either the Exhibition or the Industrial University, if it can increase the utility of our Mechanics’ Institutes, and diffuse their advantages among large numbers of our people. Its exertion in calling the great meeting of delegates from these Institutes on the 18th May, 1852, proves that it has a single-minded desire to secure this end; and if success wait on this endeavour, that day will be a memorable one. To ascertain the nature and character of these Institutes, what are their defects and advantages, and, above all, how they can be improved and their powers of good developed, will materially contribute to that great object.

The history of Mechanics’ Institutes has usually been dated from the 2d of December, 1823, when the London Mechanics’ Institution was formally established. Some controversy has existed as to who first founded these Institutes. The highest merit seems rather for first making them known and appreciated, than for any actual discovery, since voluntary isolated associations of the kind existed prior to the above date. With the London Mechanics’ Institute originated a movement of the most important kind, which gave a clearly defined purpose and shape to wants that the progress of civilisation had created. That which has been said of the art of printing is true of the Mechanics’ Institute, viz. that if it had not been discovered in the way it was, the time had come when it must have been discovered, for it had become a necessity of the age. A self-governing machinery for the purpose of diffusing knowledge among the labouring classes, could have no existence when arts, sciences, and literature were regarded as the refined luxury of a few — when the labourer was considered simply as a superior sort of cattle grown for the behoof of his master, endued with no higher qualities than strength and obedience, and whom cultivation would not only unfit for his station, but render less happy. We are far from thinking such notions extinct — we know they are not; but they survive only in those nooks where the belief in witchcraft, and other absurdities of our forefathers, still linger, and in another generation the schoolmaster will have chased them utterly away.

There is little doubt that the general establishment of Sunday Schools did very much to prepare the way for the establishment of Mechanics’ Institutes. Reading and writing were taught to the children in them, with which evening classes were afterwards connected for the instruction of adults. In 1789 a society was established in Birmingham for instructing young men. Writing, book-keeping, arithmetic, geography, and drawing were taught, lectures were delivered, a library was formed; in fact, the “Sunday Society,” or, as it was afterwards entitled, the “Birmingham Brotherly Society,” resembled in most respects a large number of Mechanics’ Institutes of the present day. In 1796, Anderson’s University was incorporated by the magistrates and council of Glasgow. Dr. John Anderson bequeathed the larger portion of his property for “the improvement of human nature, of science, and of his country.” The University was to consist of four colleges besides a school. The four colleges were for the arts, medicine, law, and theology. The subjects taught, and the other arrangements, sufficiently show that the Institution was not contemplated for the operative classes, but for those in the middle rank. Fortunately for the former, in three years after the establishment of the university (1799), Dr. George Birkbeck was appointed the professor of natural philosophy. He required apparatus for his lectures, and the Glasgow of that time (not one-fifth of the present Glasgow) could not furnish it without a resort to the workshops, and this brought him in contact with the mechanics and artizans. He perceived their deficiency in scientific information; he learnt their wish to remedy this want, and resolved to supply them with the means. Why, said he, are these minds left without the means of obtaining that knowledge they so ardently desire? Why are the avenues to science barred against them, because they are poor? He resolved to offer them a gratuitous course of elementary philosophical lectures. To treat his proposal as “visionary” and “absurd,” was but to repeat the welcome which the would-be wise have bestowed on every improvement since the world began. They predicted “that if invited, the mechanics would not come; that if they did come, they would not listen; and if they did listen, they would not comprehend.”1

Sizzi the astronomer assailed the discovery of Jupiter’s satellites by Galileo in the same style. “The satellites are invisible to the naked eye, and therefore can exercise no influence over the earth, and therefore would be useless, and therefore do not exist.” Birkbeck, like, Galileo, chose to believe his own, rather than any secondary testimony. The offer was made to them, — “they came, they listened, and conquered, — conquered the prejudice that Avould have consigned them to the dominion of interminable ignorance.” Dr. Birkbeck conducted his “mechanics” class for four years. On his removal to London in 1804, Dr. Ure, his successor, carried it on with equal zeal and success, and in 1808 added a library. For a few years it continued; then it declined, owing to the neglect of the managers of the University; then was revived; and ultimately seceded altogether in 1823, and formed the Glasgow Mechanics’ Institute, five months previous to the formation of the London Mechanics’ Institute. In the same month was established the Liverpool Mechanics’ and Apprentices’ Library. Previous, however, to either of these institutions being established, there had been formed, in April, 1821, the Edinburgh School of Arts (now the Watt Institution) by Mr. Leonard Horner. Of this Institution we shall have to say more hereafter, as it is one of the very few Institutes in the kingdom which, so far as the plan of instruction is concerned, is worthy of imitation. It was not, however, till the establishment of the London Mechanics’ Institute, that the subject began to attract general attention. In 1814 Mr. F. Dick wrote five papers in the Monthly Magazine on the formation of Literary and Philosophical Societies for the humbler classes, containing many valuable suggestions. His proposals seem to have scarcely attracted any notice. In 1817 an Institution entitled the Mechanical Institution was established in London; but neither this, nor the Glasgow, the Liverpool, or the Haddington Institutes, all of which were established in the same year, and previous to the London Mechanics’ Institute, awakened public attention to the subject, any more than the labours of Dr. Birkbeck in Glasgow twenty-three years previously had done. To him is undoubtedly due the honour of having originated the system of offering scientific instruction in an accessible form to the working classes. But the honour of establishing the London Mechanics’ Institute twenty-three years later, and which gave the first impulse to the subject throughout the provinces, must be shared by the editors of the Mechanics’ Magazine, Messrs. Robertson and Hodgskin, especially the former, who proposed it in an article on the subject in the number for October 11th, 1823. Dr. Birkbeck, on its proposal, immediately took an active part in promoting it. Henry Brougham advocated it, and, in an article on the scientific education of the people in the Edinburgh Review of October, 1824, signed “William Davis, gave the subject publicity, and stimulated to the formation of many of the provincial Institutes. The proprietor of the Morning Chronicle and Observer newspapers put down his name for one hundred and twenty guineas; and altogether it received donations in money to the amount of above a thousand pounds in the first year of its existence. At its second anniversary, the Duke of Sussex presided, around whom were clustered many of the active men of the day,— Brougham, Denman, Hobhouse, Lushington, Birkbeck, and other less known personages, that the lapse of a generation has consigned to oblivion. A large building was purchased at a cost of 4000l., of which 3700l. was advanced by Dr. Birkbeck, and two-thirds of this sum remains unpaid to this day. For this munificent aid, which had an effect on the formation of Mechanics’ Institutions analogous to that which the Liverpool and Manchester Railway has had upon railway locomotion, — for this truly national service, the government had the generosity the other day to offer 50l. per annum to Dr. Birkbeck’s widow, an offer which was declined.

The publicity given to the nature and objects of these Institutions by the auspicious commencement of the London Mechanics’ Institution, speedily led to their establishment in the principal towns. In 1824, Institutions were established in Aberdeen, Dundee, Leeds, Newcastle on Tyne, Alnwick, Dunbar, and Lancaster; and in 1825, in Manchester, Birmingham, Norwich, Devonport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Ashton, Bolton, Hexham, Ipswich, Lewes, Louth, Shrewsbury, Halifax, Hull, and other places.1

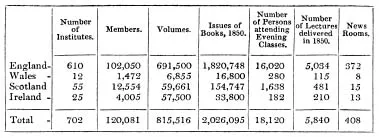

The present year will witness the thirtieth anniversary of the establishment of the London Mechanics’ Institute. In that period Institutes of the same nature, but established under various names, as Mechanics’ Institutes, Literary Societies, Mutual Improvement Societies, have increased to the number of 700, containing 120,000 members, thus classified2:

This summary does not, probably, contain the whole number, and is certainly rather under than over the truth.

It would be difficult to estimate too highly the amount of good which this vast machinery has effected. We have not indeed, in these prosaic figures, the record of any great event,—of one of those deeds which strike men dumb with admiration or amazement. There is nothing to attract the novelist to weave around it the ornaments of his fancy, — little perhaps to tempt the historian to linger on the record; yet how trivial, in relation to human weal, are many of their themes compared with this! Mechanics’ Institutes have become an element of English life—a power acting and reacting for good on thousands and tens of thousands of our population, and, through them, on yet unborn generations. Histor...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Chapter I.

- Chapter II.

- Chapter III.

- Chapter IV.

- Appendices.

- Index