![]()

V

Co-Ordinates

[Extracts from: 'The Child's Conception of Space' by Jean Piaget and Barbel Inhelder (Routledge and Kegan Paul), 1956]

IT HAS LONG SINCE been accepted that drawing can be used to help in the assessment of children's mental development. Many teachers will know, for instance, of the 'Man Drawing Tests' of Burt and Goodenough. These are simple tests to administer: one asks a child to draw the best figure of a man that he can, then this is compared with drawings representing the average ability of children of different ages.

It is perhaps less often that we as teachers examine children's drawing from the point of view of their understanding of space as revealed in their attempts to represent it. The pictures with a band of blue sky at the top and of green grass at the bottom of the page are familiar sights in infant school classrooms. The gap between sky and grass is puzzling to adults. 'What's that?' a teacher asks. 'Nothing', replies the child, 'just air', or something like that. We all know the difficulty children have when they first try to draw a house in three dimensions; two sides which should be at an angle are usually on a straight base line.

A face in profile has its problems too, very often two eyes are represented, and if a person on a bicycle or see-saw is drawn, then usually we see both legs appearing on the same side of the object, the need to show in some way that one leg is behind the other is not realised, and the problem of how to do it proves too difficult. All these anomalies and others can easily be seen in the drawings of young children.

It is quite obvious that children do not perceive these things in any unusual way, they have the same sensory stimuli as we have i.e., they never see a gap between the sky and the grass, why is it then that they represent their world in this way? Piaget has tried to find an answer to these questions. In the first place he shows that children's spatial ideas rest on 'primitive' topological relationships—things are together or separated, discrete or continuous. For the child the sky and the grass are separated, one up there, the other down there, so that is how he represents them. The person on the see-saw is 'next-to' the see-saw, the more subtle relationship of the legs is not apprehended. The next stage, as Piaget has shown, is when a child can take into account different viewpoints and perspective. In drawings at this stage one finds attempts to make a figure smaller because it is in the distance, and to represent one thing in front of or behind another. But there is still a further development to take place, that is when all objects in a drawing can be co-ordinated, each one related to the others in size, proportion and distance and all placed in relation to the framework of the picture.

It is the development of the use and understanding of horizontal and vertical axes that Piaget examines in the chapter to be discussed.

"Systems of Reference and Horizontal-Vertical Co-Ordinates". (Chapter XIII)

"As adults we are so accustomed to using a system of reference and organising our empirical space by means of co-ordinate axes which appear self-evident (like the vertical provided by the plumb-line and the horizontal given by a water level), that it may seem absurd to ask at what age the child acquires these ideas. It will be said that as a result of lying flat on his back the child is aware of the horizontal right from the cradle, and that he discovers the vertical as soon as he attempts to raise himself. The postural system would thus appear to provide a ready-made co-ordinate space, the organs of equilibrium with their only too-well-known semicircular canals solving the entire problem. In which case it would indeed appear odd to want to raise the problem all over again with the 4 to 10 year old child!

Here we touch on one of the worst misconceptions which has plagued the theory of geometrical concepts. From the fact that the child breathes, digests, and possesses a heart that beats we do not conclude that he has any idea of alimentary metabolism or the circulatory system. At the very most he may have noticed that his movements in breathing, or felt his pulse. But such perceptual-motor awareness does not lead to any understanding of the internal phenomena of which these movements are only the outward and visible sign. Similarly, from the fact that he can stand up or lie flat, the child at first derives only a strictly practical awareness of the two postures and nothing more. To superimpose upon this a more general scheme he must at some point go outside the purely postural field and compare his own position with those of surrounding objects, and this is something quite different from practical knowledge ...

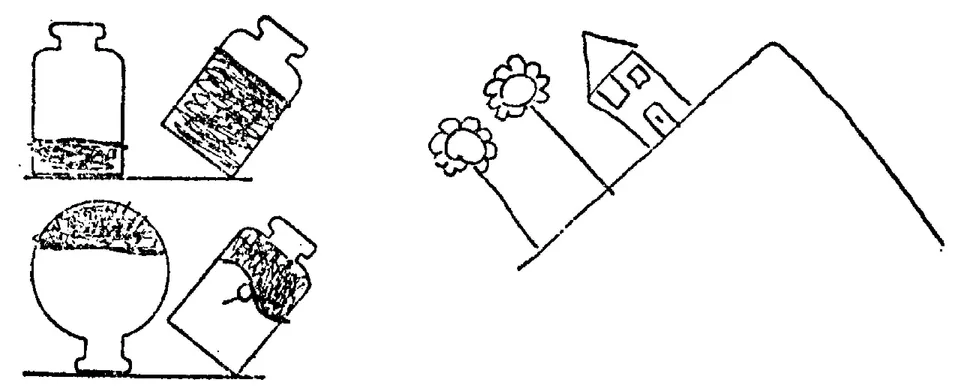

As for concepts proper, everyone has seen the kind of drawings which children produce between the ages of 4 and 8, showing chimneys perpendicular to the slopes of roofs and men at right-angles to hills they are supposed to be climbing. In such drawings we have at one and the same time an awareness of right-angles inside the figure, together with a total disregard of the vertical axis. This suggested that the child has a long way to go in passing from a postural or sensori-motor space to a conceptual one. Nevertheless, the majority of authors cover this distance at a single leap by attributing a full-blown system of co-ordinates to these primitive intuitions.

Hence there is nothing absurd or unreal about the problems we are proposing to examine. On the contrary, it is in terms of the genuinely operational concepts acquired around 7 or 8 years, and not prior to their construction, that the development of reference frames takes place, including those based on the physical notions of horizontal and vertical..."

(Page 378.)

Method of Investigation of the Horizontal

"For the study of the horizontal the following method was found best. The children are shown two narrow-necked bottles, one with straight, parallel sides and the other with rounded sides. Each is about one quarter filled with coloured water and the children are asked to guess the position the water will assume when the bottle is tilted. Some empty jars are placed before the child, the same shape as the models, on which he is asked to show with his finger the level of the water at various degrees of tilt. In addition, the youngest children are asked to indicate the surface of the water by a gesture so that one can be sure whether or not they imagine it as horizontal or tilted. The experiment is then performed directly in front of them and they are asked to draw what they see. Children over 5 (on the average) are given outline drawings of the jars at various angles and asked to draw the position of the water corresponding to each position of the bottle, before having seen the experiment performed. Naturally, the various inclinations are presented in random order to avoid perseverative errors

(the kind in which a child repeats the same answer without further reflection because of the persistance of an idea or image).

Care is also taken to make the children draw the edge of the table, or the support holding the bottle, in such a way that this horizontal, directly perceived, can assist in judging the position of the liquid. As soon as he has made this drawing the child compares it with the experiment which now takes place. He is then asked to correct it or produce a new drawing and so passes on to other predictions. Care was taken to have the level of the water at the height of the child's eves, or a little above, so that he can see the edge of the surface clearly."

(Page 381.)

Method of Investigation of the Vertical

"For studying verticals the following methods were employed. Firstly during the preceding experiment on the jars of water, we floated a small cork on the surface of the water with a match-stick rising vertically from it. The child is asked to draw the position of the 'mast' of this 'ship' at different inclinations of the jar and then correct his drawing after seeing the experiment. Secondly, we suspended a plumb-line inside the jars (now empty), the plumb-bob being shaped to represent a fish. The child has to predict the line of the string when the jar is tilted at various angles. This done, the experiment of actually tilting the jar is performed and the child is asked for further drawings. Thirdly, the child is shown a mountain of sand, plasticine etc., and asked to plant posts 'nice and straight' (upright) on the summit, on the ground nearby, or on the slopes of the mountain. It is very important to get him to make clear what he means by 'straight' and 'sloping' in referring to the posts (a selection of drawings helps the experiment along). The child is also asked to draw the mountain, showing the posts either 'nice and straight' (upright) or sloping. Finally, we sometimes combined the experiment using the plumb-line with that of the mountain, by getting the child to predict the direction of the string when the bob was suspended from hooks projecting from posts planted on the sides or on the summit of the mountain ..."

(Page 381.)

Stage I: Inability to Distinguish Surfaces or Planes, in the Case of Either Fluids or Solids. (This Is an Example Where the Suggested Stage Zero Would Be Appropriate)

"The first stage lasts until about the age of 4 to 5 years. When the children are asked to draw the level of the water in a bottle or the trees on the side of a toy mountain their reaction is extremely interesting, for they are unable to distinguish 'planes' as such. Consequently, they show the liquid neither as a line, nor as a surface, but as a kind of ball (as soon as they get beyond mere scribbling). They think of the fluid in purely topological terms, merely as something inside the jar, and not according to euclidean concepts like straight lines, planes, inclinations, and dimensions. Here are some examples:

VIL (3; 0). Even with the bottle standing upright Vil can only show the water in the form of scribbles extending beyond the walls of the jar, supposed to indicate the liquid inside the bottle (drawn by the experimenter).

DAN (4; 1) has a straight-sided bottle drawn for him. Asked to draw the contents he shows the water as a blot on the left-hand side near the neck. Yet he can copy lines when these are drawn in, though unable to orient them correctly, even with the bottle upright.

MAN (4; 6) draws the water inside the jar as a kind of little ball situated regardless of the sides or base of the bottle, whatever the angle of tilt. We then drew for him lines representing the horizontal level (or the horizontal and vertical axis) with the bottle in two positions, upright and sideways, asking him to put in the water. He draws his little round blots inside the bottle whether it is upright or lying down.

For the vertical axis, here are some equally amusing examples:

NIL (3; 11). Shown a mountain with a slope of 45°, he draws the trees and men parallel to the base, then two houses stuck to the slope by their side walls, the base of the building including the doors, which are carefully drawn, thus remaining suspended in midair.

GEH: (4; 2) draws houses and trees, some lying along the slope, others against the background of the mountain but placed haphazardly so that it is impossible to tell whether he visualises them as located on the slope seen full face or simply stuck to the object.

KUP (4; 11) draws the houses not only sloping with the mountain but turned at all sorts of angles, including one with doors, windows, chimney and column of smoke, all upside down, the base in midair and the roof underneath with smoke descending from the chimney at about 20° from the vertical. Yet when Kup is asked what direction one must follow in order to climb the mountain he naturally points out the correct way.

BER (4; 8) draws the trees as did the previous children, more or less parallel with the edge of the mountainside but inside the line as if he were afraid of Locating them in empty space. He is asked whether they stand upright or slanting. 'They're all standing upright. I don't know how to make them sloping.' So he sees them as upright like his own body, though he draws them slanting. On the other hand, the plumb-line (a button hung from a needle) produces the remark, 'It's going to fall to the ground', though the line he makes is only vertical when the path of the thread is not influenced by the sides of the mountain but is perceived relative to his own body. In other cases the thread is drawn oblique, not because the button is imagined as rolling down the slope, but because seeing the needle in profile on a ledge overhanging empty space, the child refuses to let the thread fall straight into empty space, but gives it an angle as if the mountain attracted the object instead of letting it fall vertical!"

(Page 384.)

Intermediate level IIB-IIIA

These examples enable us to understand the absence of reference to a co-ordinate system, i.e., the orientation of the jars from vertical towards the horizontal and the relationship of this to the water level go unnoticed by the children. The relationship the children present are topological (see page 33), i.e., the water is in the jar, so 'in-ness' is represented by a blob or scribble within the walls of the jar, regardless of the water level's relationship to the sides. Similarly trees and houses are 'next to' the mountain so they are carefully placed in proximity but without regard to the correct orientation.

Sub-Stage IIA. Water Level Shown Parallel with the Base of the Jar and Trees Perpendicular to the Mountainside

"When the child learns to abstract the surface of the liquid as a plane and locate the trees relative to the mountainside he still fails to grasp the orientation of the water in a tilted vessel or that of the trees to an inclined slope. In the case of the water he thinks of it as moving toward the neck of the bottle, but not by simple displacement. He imagines it as expanding, increasing in volume, and it is because of this increase that it draws nearer the neck as the jar is tipped, while the surface remains parallel to the base.

WIL (5; 3). 'We're going to tip the jar over like this. What will the water do? It will move. How will it move; where to? Show it on the glass—(He points to a level 1 cm. higher than the present one, all round the bottle, parallel to the base)—And if we tip it the other way?—(same reaction)'. He is asked to draw the level on jars sketched in outline and tilted at various angles. He produces a water-line parallel to the base in each one. 'Show me the position the water will move to with your fingers on the glass again. (He once more shows the water-line parallel to the base)—Now look and see if that's right. (The jar is tipped while he actually has his finger in the position he predicts for...