eBook - ePub

Women's History and Local Community in Postwar Japan

Curtis Anderson Gayle

This is a test

Share book

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women's History and Local Community in Postwar Japan

Curtis Anderson Gayle

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Examines the emergence of women's history-writing groups in Japan.

Uses interviews conducted with founding members and analysis of primary documents and publications by history-writing groups

Will appeal to students and scholars of Japanese History, Asian History, Women's Studies, Historiography and Marxism

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Women's History and Local Community in Postwar Japan an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Women's History and Local Community in Postwar Japan by Curtis Anderson Gayle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

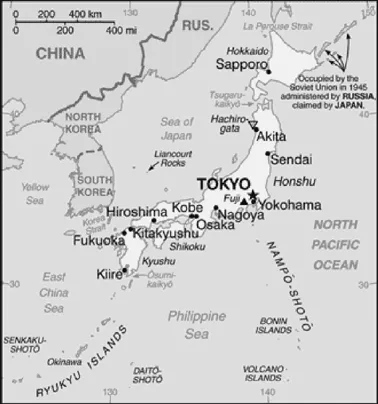

Map 1 Japan

1 History, liberation, and difference

History as an open-field of possibility

It is hardly surprising that local women's history (chi'iki josei-shi) in Japan dates back to the early years after World War II, a time when history-writing in general was becoming an open and accessible field of social practice.1 Through the writing of history, women in local regions of Japan were able, during the years shortly after the war, to engage in what might be called “subject-creation” by raising their voices and putting into practice their own distinct forms of historical representation.2 These were to have an impact not only on the way people thought about history, but also on the ability of history to fulfill its postwar promise of providing a voice to those who had previously been excluded from historical space and historical narratives in modern Japan. In taking up three foundational examples of local women's history in the early postwar era, this book will examine the formative years of this most interesting and vital form of historical representation and will also shed light upon why it continues to have social and historiographical relevance in the contemporary era.

The emergence of women's history-writing groups in Tokyo, Nagoya and Ehime suggests that women's history, once seen as simply derivative of western feminist history or early postwar forms of “small history,” such as social history or “people's history” (minshū--shi), actually developed in context of early postwar history-writing movements and ideas in ways that reveal the creativity, independence and boldness of its founders.3 Three groups stand out in this scenario: the Women's History Research Society in Tokyo (Josei-shi Kenkyūkai—founded in 1946), the Nagoya Women's History Research Society (Nagoya Josei-shi Kenkyu-kai—founded in 1959) and the Ehime Women's History Circle (Ehime Josei-shi Sā-kuru—founded in 1956). While the first of these groups sought to make history-writing an activity in which the most ordinary of women could participate on a nationwide scale, the latter two groups focused particularly upon their own local areas of Japan and how mothers, housewives, working-women, farming women, and women from all walks of local life might begin to utilize the writing of history as a way to bring about a more sophisticated form of consciousness to help develop the agency, or subjectivity, of women more generally. In taking up the emergence of local women's history in early postwar Japan, this study will show how certain women, in the words of anthropologist Nicholas Dirks, saw in the writing of history potential “levers for the struggle of new groups” and “suppressed voices” to declare themselves historical subjects and agents of social change.4

This declaration of historical subjectivity did not take place in a vacuum. Women in each of the three groups to be discussed were, to varying degrees, involved in women's movements and activities usually associated with attempts to raise the consciousness and active subjectivity of women. In order to better grasp the reasons for their choice of history-writing as a means to do this, it is helpful to look at the issue from the vantage point of how women in Tokyo, Nagoya and Ehime approached the problem of subject-creation through this specific activity of writing history in their own voices. What was it about history and history-writing that caught the attention of women seeking to create new forms of representation and self-authorization after World War II? Why did views toward history-writing during the early postwar years suggest it could in fact become an individual and social enterprise potentially open to everyone? Most importantly, how did specific women in Tokyo, Nagoya and Ehime interpret and appropriate these beliefs in ways that spoke directly to their own interests as women intent upon utilizing history in order to change themselves and their environs?

Perhaps one important place to begin tracing popular views toward history-writing shortly after World War II is to discuss the overall climate in which the discipline of history was situated. Economic, social and cultural transformations underway after World War II presented both challenges and opportunities for those interested in writing new kinds of histories. The Allied Occupation of Japan, lasting from 1945 until 1952, undertook major reforms in many areas of Japanese society based on the assumption that feudal aspects of socio-cultural behavior had, at least in part, driven the Japanese military into the Pacific War with the United States.5 As the Cold War with Soviet Union became an overwhelming ideological issue for America by 1947, however, Occupation policy began to emphasize economic re-consolidation in order to make Japan a “showcase” for capitalism in Asia. Ideologically speaking, this “Reverse Course” meant that labor unions and figures associated with the Japan Communist Party, who had immediately after the war been treated as heroes for their resistance to Japanese fascism and imperialism, suddenly came to be seen as subversive elements that were endangering Japanese economic recovery and political re-consolidation.6 Labor unions and the left, conversely, saw the new policies of the Occupation, in particular the rehabilitation of the wartime elite for sake of capitalist economic growth, as ominous signs of a possible return to fascism, this time under the auspices of external imperial powers such as the United States. From 1947 through the early and mid-1950s a vicious circle ensued: state-driven paranoia toward progressive movements and figures by the Occupation, leading to crackdowns and arrests, which in turn sparked greater efforts by the left to achieve revolution. For the Occupation, any mention of the word “revolution” signaled a “foreign” and destructive form of authoritarianism that threatened to wash away American influence in East Asia.

The formal end of the Occupation in 1952 did not rectify this mutual mistrust. The conditions under which Japan regained its sovereignty only seemed to heighten the adversarial relationship between the radical left and the state. Legal and political arrangements made between the now-rehabilitated wartime elite and the Occupation included the permanent presence of American forces in Japan, continued American rule over the island of Okinawa, and the legal-contractual basis for a long-term security treaty between Japan and the US (the US-Japan Security Treaty) that would tie the fortunes of Japanese reconstruction and foreign policy to its larger relationship with the United States.7 As far as many progressive intellectuals, labor unions, students and others were concerned, the formal end of the Occupation did not mark the reconstruction of Japanese sovereignty but, instead, merely fortified a regime of conservative rule whose views and values had not changed since the wartime period. To make matters worse, in 1955 the political re-consolidation of conservative elements in Japanese society was made complete with the merging of the Liberal Party and Democratic Party into the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), and what is known as the “1955 System” that has only very recently been overthrown.8

These developments helped produce and sustain an atmosphere in which history-writing gradually became an important means for galvanizing popular resistance to the state and to empire. Certain monumental events were taking shape by the late 1940s and early 1950s, events that would provide a discursive and epistemological grounding to the overall idea that history-writing was not just an exercise in chronicling the past but was, instead, an integrated practice of thinking and acting that carried with it the potential to achieve various kinds of changes on the political, economic, cultural and social levels. The story here begins, then, not only with the emergence of three noteworthy and intriguing women's history-writing groups, but also with a wider investigation into exactly why history-writing became so important for certain women, in far-flung regions of Japan, intent upon creating new spaces of thought and action within the lives they led and the places they lived.9 As this author has elsewhere pointed out, from the late 1940s, the writing of history became for many a potentially revolutionary activity that spoke directly to the desire of some on the margins of Japanese society to bring about changes in both consciousness and in everyday material life.10

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, a good number of Marxist historians began to organize a series of nationwide campaigns collectively referred to as the “People's History Movement” (Kokuminteki Rekishigaku Undō).11 In this movement, Marxists encouraged women, farmers, factory workers, out-castes, and others to begin writing their own histories and those of their workplaces and local communities. Not only did this approach de-professionalize the writing of history by making anyone a potential participant and subject, it also de-mystified history by bringing it squarely into the realm of material culture and everyday life, or seikatsu.12 This meant that ordinary people interested in writing history would not need to compose documentary histories based upon formal records, but could instead utilize personal/biographical recollections as well as rich local traditions of oral history, myth, and legend, much as the French Annales School had advocated in the prewar and postwar eras.13 This position was, in fact, supported by a good deal of public memory at the time, which imaged and articulated prewar historiography in Japan as having been nothing other than the instrument of the academic elite and, ultimately, the state apparatus. Even Marxist historians, by their own postwar admissions, had not been able to create a bridge between the writing of history and everyday life during the prewar years.14 History in the postwar era would, according to this narrative of contrasting fortunes, now need to be taken up directly by individuals and groups on all levels and regions of Japanese society.15

In a fundamental sense, the early postwar discipline of history and practice of history-writing became vehicles through which to contrast the past and present, fascism and democracy. As Carol Gluck argues, the early postwar era was a time in which Marxist historians and intellectuals sought to “diagnose” what was wrong with Japan in order to prepare the way for a better future.16 Several young Marxist historians during the late 1940s and 1950s brought into the idea of history-writing the notion that it could actually become a tool of empowerment and subject-creation for the working-class, women, and those who might be today called “sub-altern.” Inoue Kiyoshi (1913–2001), Ishi-moda Shō (1912–86), Uehara Senroku (1899–1975) and Matsumoto Shinpa-chirō (b. 1913) each believed that history could show why Japan had fallen into its dark years and what it needed to do in order to build a new tomorrow.17 Marxist historians were eager to sever history not only from its past political ties to statism and imperialism, but as well from its one-time links with academic elitism. This helps explain why they worked diligently to come up with practical views of history as a scientific enterprise that could also speak directly to the problem of greater popular participation in social and political change.18 In Benedetto Croce's words, during this period history was very much “related to present needs and to situations in which these events find their echoes,” so that ultimately history became “knowledge of the eternal present.”19

Marxist historians such as Ishimoda Shō, to take one of the most noteworthy examples, shortly after the war declared prewar attempts at history-writing to have utterly failed in the crucial task of “bringing history to the people.”20 Historians such as Ishimoda were convinced that without the mobilization of the working-class, including women, to become more aware of their past and present subjugation—something that could be assisted by the process of writing one's own history in the voice of the existential present—it would be impossible to bring about any kind of significant or lasting change for women and the working-class. In this sense, historians like Ishimoda, and the movements they led, sought to make history-writing something akin to what Josephine Donovan has recently called a “revolutionary praxis,” or a “free, creative engagement in the world” within the sphere of everyday life.21

As a new “revolutionary praxis,” history-writing could provide an interface through which women, students, farmers, and others could become central to the formation of a “cultural awakening” that would lead to a greater sense of historical and social responsibility (or “revolutionary subjectivity”) for the working-class and women in Japan.22 Indeed, the popular phrase “people's histories” (jinmin no rekishi) carried with it a quasi-ethical sense of responsibility for the working-class, and others whose voices had long been silent, to directly make their impact on the historical landscape and the public sphere. Since the central issue concerned how women might begin to write histories on their own terms and in their own voices, however, such attempts to write people's histories cannot be understood as simply a collage of disparate voices seeking inclusion and input within an overarching and homogeneous conception of historical change, or revolution. These should, instead, be seen as early attempts to bring into more democratic and populist versions of history voices which had long been silent in official narratives. Even though burgeoning local (chihō-shi) and prefectural (ken-shi) forms of history did not give adequate voice to women in the early postwar era, Marxist approaches to history writing did hold out the promise of becoming a practical means by which to leverage the individual agency and social responsibility of those long denied access to Japanese history. Japanese forms of Marxist history-writing, in other words, supported the idea that women, whose voices had been excluded from past historical narratives and spaces, now had to be included on their terms and in their own specific ways.

Fresh memories of the war, and the mobilization of everyday life under a fascist regime, fuelled this common progressive desire for greater self-reflection and subjectivity.23 As the political historian Maruyama Masao hypothesized shortly after the war, ordinary Japanese people had been denied their subjectivity or agency by the wartime system; a new direction for Japanese history and politics now mandated it crucial for all citizens—including women—to engage the public sphere in multiple avenues and discourses.24 In this important respect, the early postwar ...