![]()

Part I

Thinking critically about events and sustainability

![]()

1 Events, society, and sustainability

Five propositions

Tomas Pernecky

Introduction

Events are important not only to individuals but also to civilisations. Many a sociologist, anthropologist, and historian would agree that events have always been a part of societies, although they may have taken on different forms, meanings, and significance. They serve specific functions in the ways we interact with one another, and play a part in the structuring and maintaining of societies. If we were to stop and think about all of the events commencing daily around the world – from festivals embedded in rich traditions, to religious events, conventions, and political rallies, we come to the realisation that this phenomenon is inseparable from the fabric of humanity. Events not only reflect the ‘mood’ of a people, they express community values, visions, and hopes, and speak of the environments in which they take place. Built into the socio-cultural systems, events are intertwined with many aspects of our lives, traversing the social, political, cultural, economic, historical, and psychological dimensions.

It is therefore appropriate to begin by stating that the term ‘sustainability’ ought to reflect the immensity of the events phenomenon. Sustainability and events research then should also extend to understanding the various roles and functions of events in societies. With the exception of a few scholars, the sustainability–events nexus has followed a single train-track, and mainly attended to environmental concerns, and less to the social and cultural aspects of events. If not deemed sustainable, events can be depicted as a ‘problem’ for the environment, which has led many authors to focus largely on management models and the impacts of events. The overarching aim of this chapter thus rests on a claim that there is a lot more to sustainability and events than is widely acknowledged. The following pages attempt to address the complex relationship between events, society, and sustainability beyond the prevailing environmental focus, and to explore how these intersect, so that new horizons of sustainability can emerge.

With regard to defining events for the purpose of this chapter, the operating presumption is that the vast majority of events have a cultural aspect, often require some level of organisation, and have an element of commonality which draws people together – whether motivated by particular interests, needs, cultural imperatives, or ideology. The character of the work presented is conceptual, and allows for events to be tackled broadly as temporal gatherings for a common purpose: as the ‘coming together’ of people. The term ‘events’ is therefore used in a broad sense to signify an aspect of human activity that pertains to modes of socio-cultural being, that is worthy of enquiry. Importantly, events are taken as a phenomenon that is inherent and significant to humans and society, a recognition that strengthens the field of Event Studies as a domain of important knowledge and experience.

How did we arrive at talking about sustainability?

The present worry about sustainability is a consequence of man’s capability to understand and manipulate the resources of earth.

(Faber et al. (2010, p. 11))

Sustainability is not something that can be artificially divorced from the actions of individuals and the ways societies function. Sustainability, as we understand it today, is a contemporary issue, and the lack thereof, is closely linked with social problems for it implies undesirable outcomes. This opposite spectrum can be given the label ‘unsustainability’. In other words there is something that at least some members of a society perceive as a problem. In this case, it is the lack of sustainable practices, careless decision making, and resource-intensive modes of operation that may pose a risk to society and its survival. Known as the subjective element of social problems, it is given a momentum when part of society believes that a certain condition will decrease the quality of human life – a belief that something is harmful and should therefore be changed (Mooney et al., 2011). Much of the sustainability discourse arises out of such concerns, impacting many facets of our lives: from business, to politics, to increasing areas of science.

There is also the objective element in the study of social problems that refers to the existence of a social condition which we can for example experience, learn about, or be exposed to through media (Mooney et al., 2011). Seeing children begging for food, being exposed to poverty, living in a neighbourhood with a high crime rate, witnessing inadequate housing – all of these are examples of the objectivity of social problems. This objective element in relation to sustainability, however, is a lot more problematic as there is no unified consensus on what counts as unsustainable behaviour or practice, and debates of this nature are met with great controversy and disagreement. Economic growth, for instance, is believed to be necessary for the reduction of poverty, but is not so welcome when speaking of environmental protection. This is one of the moot points in sustainable discourse (for greater insights see Verstegen and Hanekamp, 2005).

Loseke (1999, p. 25) further explains that ‘constructing a successful social problem requires that audiences be convinced that a condition exists, that this condition is troublesome and widespread, that it can be changed, and that it should be changed’. She adds that, as used in social construction perspectives, ‘a claim is any verbal, visual, or behavioural statement that tries to convince audiences to take a condition seriously’ (p. 39) (original emphasis). A fitting generic example may be the well-known Al Gore documentary about climate in crisis An Inconvenient Truth (www.climatecrisis.net). Events-related claims driving the sustainability agenda are often underpinned by environmental concerns such as global warming, the rise of carbon dioxide, and pollution. The claims we are exposed to can take the form of a press article such as the case below:

The ongoing 2010 World Cup has been in the design news for all the wrong reasons. Everybody’s spent a lot of time griping about the design of the new ball, but more serious problems have emerged now. The whole event, it turns out, is an ecological disaster. According to a recent study undertaken by the Norwegian government (bless those Scandinavians!) the World Cup will have a carbon footprint of 2,753,251 tons of CO2, equivalent to one year’s emissions from one million cars.

(Rajagopal, 2012)

Statements like this one are designed to make us think in certain ways. Many authors, academic or not, who write on the subject of sustainability, environmental issues, and the need to ‘green up’ the events industry tend to re-affirm that there is a problem that ought to be addressed. In the study of social problems, such claims serve the purpose of convincing audience members ‘how to think about social problems and how to feel about these problems … to think and feel in particular ways’ (Loseke, 1999, p. 27). While it is not the purpose of this chapter to examine whether any such claims are just or not, it is necessary to consider the process of constructing social problems and the possible implications in the context of events.

The field is in the process of evaluating, negotiating, and grappling with the complex issues of sustainability, leaving some looking for truth in the words and statements that surround us. Yet ‘truth’ doesn’t necessarily matter in the social problems realm – what matters is what people believe is true and therefore all that matters is ‘whether or not audiences evaluate the claims as true’ (Loseke, 1999, p. 28). Put differently, it is knowledge versus popular belief. To a critical thinker, it would appear that the treatment of events depends on the constructed views on what it means to be sustainable and what falls out of the perimeters and is thus deemed as unsustainable. The first proposition therefore makes an argument for critical assessment of claims on sustainability in Events Studies.

Proposition 1 Sustainability is a concern closely related to social problems. It speaks of the contemporary action, behaviour, and attitudes of humans and society. Future events research ought to tackle sustainability critically in order to understand the forces, impacts, and consequences interconnected with sustainability discourse.

It is more important than ever for businesses to be ‘good’ and to demonstrate that they care about people and the environment. Events, which are largely seen as business entities, if not sustainable, fall under the category of unsustainable practices and behaviour. In this light, it is easy to understand the shift towards corporate sustainability and social responsibility, but on what counts are events (un)sustainable, and are we too accepting of the claims we are exposed to?

The need for criticality

Sustainability claims can be made on different levels, in varied contexts, and will differ depending on priorities and perspectives adopted. Larsen (2009, p. 65) stresses that in our pursuit of sustainability we will do well if we search for ‘meaning and content in differing views of sustainability, rather than rushing to the conclusion of rightness or wrongness from a particular worldview’. In this regard, a critical enquiry doesn’t take sides; it turns, reveals, and examines from different points of view so more informed choices and decisions can be made, and so that richer understandings can be derived. Critical thinking is also important when questioning claims of (un)sustainability and its supporting evidence, as well as the advantages, limitations, and contexts in which such claims are made. As proposed by Bowell and Kemp (2010, p. 4), ‘critical thinkers should primarily be interested in arguments and whether they succeed in providing us with good reasons for acting or believing’.

The recent London Olympic Games were set to be the ‘Greenest Games in modern times’ (London 2012, 2007, cited in Hayes and Horne, 2011) and were also promoted as ‘sustainable Games’ – claims that have seen great controversy in recent months. Despite the pains of London 2012 to meet their vision, the sustainability aspect of this event has already been scrutinised. One of the leading UK newspapers, the Guardian (see the article by Boykoff, 2012), for example, questions the involvement of sponsors such as Dow Chemicals – a company responsible for the 1984 gas disaster in India, and British Petroleum (BP) whose environmental track record, the paper claims, is ‘dodgy’. Hayes and Horne (2011) further argue that the 2012 London Olympics model for sustainability is ‘a hollowed-out form of sustainable development’ and explain that the approach is essentially a top-down approach with a limited civic engagement. This poses a problem if sustainability is to be about people and the environment which they are part of. Proclaiming the Games as a ‘fundamentally unsustainable event’ the authors conclude that:

The lesson from London, as from other Games before it, is that sustainable development is conceptualized as ‘best practice’, ‘best available technology’, ‘green growth’ and so on; it is not a question of challenging the compatibility of economic growth with environmental remediation, nor of constituting environmental citizenship as democratic deliberation.

(Hayes and Horne, 2011, p. 759)

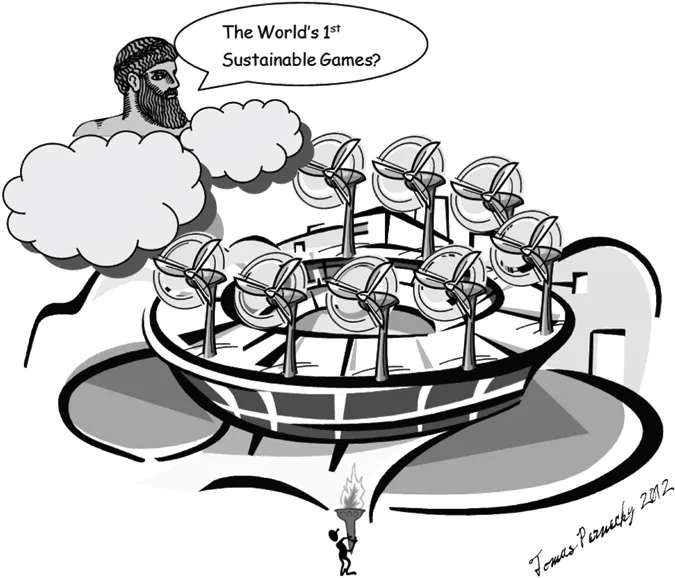

Mega, major, and hallmark events are therefore more likely to reflect contemporary concerns and the shifting socio-economic-political realities. To some extent, Figure 1.1, following, portrays the human condition in relation to events. The predicament of mega events and the events industry as a whole, is that there is an ongoing competition to have better, bigger, and newer venues so that destinations can attract large events, international crowds, and worldwide publicity. Hence the trend seems to follow the path of building more and growing more, while employing the language of sustainability. This needs to be recognised and tackled critically along with other facts such as the necessity for thousands of people to fly, drive, buy, consume, and so forth. Furthermore, one must also take into account the corporate nature of events and the involvement of companies that are willing to invest millions of dollars worth of sponsorship. The reality is that commercial decisions by large corporations are less based on sustainability and well-being, and more on growth, access to new markets, branding, and awareness-related goals. In addition, sponsorship is a multi-billion-dollar business and sponsors are key stakeholders without which many events would cease to exist.

Figure 1.1 The human condition and events.

Sustainability is therefore a messy concept, operating across several dimensions. The multilevel approaches to sustainability do indeed acknowledge that while the economic dimension may focus on competitiveness, the ecological dimension is more concerned about habitability, the social dimension with community, the ethical dimension with moral legitimacy, and the legal dimension with legal legitimacy (M. G. Edwards, 2009). This polarity in sustainable thinking is problematic because economic growth, cost effectiveness, and profitability (e.g. the economic dimension of sustainability) is not the same as preserving the environment and biodiversity (e.g. the environmental dimension of sustainability). While the first might see ‘growth’ as a necessary pathway, the second is likely to perceive it as worrisome if not alarming. This tension is particularly troublesome in assessing events, and the three pillars of sustainability that dominate the current eve...