![]()

1

ALARM BELLS RING

Before the end of April 1986, Chernobyl meant nothing to the average person. But the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power station quickly projected it into the forefront of public attention; it held a prominent position on television news bulletins and was on the front page of leading newspapers around the world for many weeks. Now the very name Chernobyl is taken as synonymous with nuclear accident. Rightly so, many argue, because it was by far the worst accident ever to occur in a nuclear power station. In terms of damage done and anxiety caused, if not immediate death toll, it also rates (alongside Bhopal) as perhaps the worst technological disaster of all times.

The accident clearly deserves full analysis and this can only be done some time after the event as the initial speculations, so eagerly and speedily broadcast through the news media, have been superceded by more sober factual accounts. The results of detailed studies of what happened, how it was coped with, and what it implies in the long term started to appear within six months, and it is now possible to reflect on Chernobyl in context.

In this book we shall look at what happened, how it affected people both locally and further away, and what lessons can be drawn from the unfortunate affair. But we should start at the beginning, when the first signs of anything untoward landed — quite literally — out of the blue over Sweden, over a thousand kilometres away.

THE STORY BREAKS

At 2.00 pm on Sunday 27 April 1986 automatic radiation measuring instruments at the then unmanned Swedish National Defence Research Institute (FDA) in Stockholm registered a marked rise in radiation levels in the air over the city. The unexpected rise must have caused alarm when it was discovered by staff who turned up for work the next morning. The cause was a puzzle to Swedish scientists.

There were only two possible explanations (other than instrument malfunction), and neither was good news. It could be fallout from a nuclear weapon and — whilst it was hoped that one had not been unleashed with serious intent anywhere — there were suspicions that the monitors might have picked up evidence of atmospheric nuclear testing believed to be under way in China. The alternative was accidental leakage of radiation from a civil nuclear installation, probably a nuclear power station. Either way, it was clear that something significant had happened, somewhere, recently.

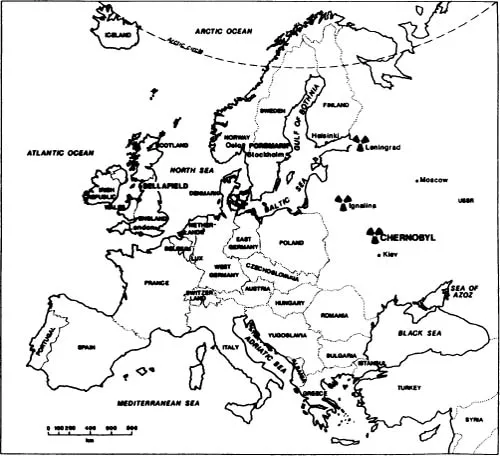

Meanwhile, the Monday morning shift was finishing at the Forsmark nuclear power station on the Baltic coast, about 100 km north of Stockholm (Figure 1.1). At 9.30 am radiation detectors 4 km from the station picked up high levels of radioactivity, and unexpectedly high levels were measured on the shift workers' clothing as they passed through the routine monitors before going home. Checks on radiation levels on soil and vegetation around the site confirmed that radiation levels were much higher than normal, at around 0.1 millisievert an hour (units are explained in Table 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The unfolding drama — location of places mentioned in the text

The obvious explanation was an undetected radiation leak on site. Operators at Forsmark have three alert conditions, depending on the level of radiation which is found. Below 0.025 millisievert an hour is blue alert; between 0.025 and 1 millisievert an hour is yellow alert; above 1 millisievert an hour is red alert (the most serious). The station was put immediately on yellow alert; the reactor was closed down, all 600 workers on site were evacuated, and the search was on for the leak. Although radiation levels were between four and five times higher than normal background levels, they were not high enough to justify evacuation of the population around the power station.

Within hours, by early afternoon on Monday 28 April, further pieces of the jigsaw became available. Monitoring stations throughout Scandinavia were now recording abnormally high levels of radiation in the atmosphere — up to six times the norm in Finland, five times the norm in Sweden and Denmark and up by half in Norway. The Swedish National Institute of Radiation Protection (SSI) announced that it had registered radiation just about everywhere in the country it looked. The Swedish Defence Ministry was quick to point out that although levels were higher than normal there was no danger to people in Scandinavia.

The hunt is on

Swedish scientists carried out detailed laboratory tests to discover exactly what was in the cocktail of radioactive material falling over the country. They found three main ingredients — traces of the noble gases xenon and krypton, fairly high levels of iodine and caesium, and heavy elements like neptunium. This chemical finger-printing allowed them to rule out the prospect of fallout from a nuclear weapon and confirmed that somewhere the core of a nuclear reactor had been badly damaged. The question was, where?

Neither Denmark nor Norway has any nuclear power stations, so they looked anxiously to their Nordic neighbours for information on the likely source. Sweden had never experienced any accidental nuclear releases of its own but its sensitive radiation detection systems, which are amongst the most sophisticated in the world, had in the past measured minute levels of radiation which had leaked from Sellafield (formerly Wind-scale) in Cumbria, north-west England — nearly 1,500 km to the south west (Figure 1.1).

Weather patterns over Europe at the time suggested that for several days the wind had been blowing northwards from Russia, up from the Black Sea around the Ukraine and over the Baltic into Scandinavia. Three likely sources of the fallout were identified, each a major nuclear power

Table 1.1 Summary of radiation terms

It is difficult to make sense of many reports about radiation, because the units used are unfamiliar to most of us. The problem is made even worse by the fact that not all reports use the same units, because of recent changes in the types of measurements used ‘New’ International System (SI) terms (becquerels, Sieverts, grays) have replaced ‘old’ terms (rems, rads, curies).

Radiation terms express three inter-related but different things:

(a) ACTIVITY : this expresses amount of radiation (more precisely, the amount of radioactivity in a substance), and it reflects the speed at which a radioactive element spontaneously decays (or disintegrates) and releases its energy.

Becquerel (Bq): the new term, corresponding to the decay of one atom per second It is much smaller than the old term curie which it replaced.

Curie (C) : the old measure of rate of decay, equal to 37 billion (37,000,000,000) becquerels. A nanocurie is one billionth of a curie, equal to 37 becquerels; a millicurie is one thousandth of a curie, equal to 37,000,000 becquerels.

These terms are often used to describe how much of a radioactive substance (eg caesium-137) is measured in air, on the ground or in food. In unit terms, these are expressed as becquerels per kilogram (Bq kg-1) (eg in vegetables), per litre (Bq 1-1) (eg in milk), per square metre (Bq m-2) (eg on the ground) or per cubic metre (Bq m-3) (eg in air).

(b) ABSORBED DOSE : this expresses the dose of radiation absorbed by a body or substance, normally in terms of energy transfer (eg joules per kilogram).

Gray (Gy) : the most recent unit for measuring the amount of radiation which produces a certain electric charge (measured in joules) in a kilogram of dry air, equal to 100 rad

Rad : a similar but older measure, equal to a hundredth of a gray (1 Gy = 100 rad). Equivalent to an energy absorption per unit mass of 0.01 joule per kilogram of irradiated material (ie 100 ergs per gram)

Roentgen : the amount of radiation which produces 0.258 coulombs of electric charge in dry air (NOTE that the coulomb has now been replaced largely by the joule). A microroentgen is a millionth of a roentgen.

(c) DOSE EQUIVALENT : this reflects the biological significance (eg to human health) of an absorbed dose of radiation, expressing potential harm regardless of the source or type of radiation.

Rem: a measure of the probable absorption of radiation by a human (regardless of the type of radiation involved — alpha, beta or gamma rays), short for roentgen-equivalent-man, being the amount of radiation which

Table 1.1 (continued)

will produce the same biological effects as one roentgen per kilogram .This unit of radiation dose is calculated by multiplying the dose (in rads) by the Relative Biological Efficiency of the type of radiation giving the dose (see Chapter Two) (ie rem = rad × RBE). This unit replaced the roentgen, and in turn has been replaced by the sievert (1 rem = 0.01 Sv)(but is still widely used amongst scientists). A millirem (mrem) is a thousandth of a rem (1,000 mrem= 1 rem).

Sievert (Sv) : new unit to replace rem, being a hundred times greater (1Sv = 100 rem). A millisievert (mSv) is a thousandth of a sievert (1,000 mSv = 1 Sv); a microsievert (μSv) is a millionth of a sievert (1,000,000 μSv = l Sv).

SOURCE: based on Salo (1986), Loprieno (1986), Hohenemser et al (1986), Wilkie (1986b)

station in western Russia (Figure 1.1). Leningrad (about 700 km east of Stockholm) could be ruled out straight away, because it did not fit the wind patterns. The next suspect was the world's largest operating nuclear reactor at Ignalina in Lithuania (around 700 km south-east of Stockholm). The nuclear power station at Chernobyl in the Ukraine could not be ruled out, although it was further away (some 400 km further in the same direction). The puzzle persisted … where was it coming from?

Diplomatic fallout

It was clearly by now no longer simply a scientific problem, the politicians had to be informed. Neither was it any longer a national problem for Sweden, it was quite obviously a major international issue which might have untold consequences. Given the massive distances the radioactive cloud must already have travelled, radiation levels close to the source must have been dangerously high, many people were likely to have been exposed to lethal doses of radiactivity, and vast areas must already have been contaminated before the cloud was detected in Scandinavia. Western observers immediately saw the prospect of this being the world's worst nuclear accident, and the most serious blow yet to the peaceful use of atomic energy.

Diplomatic wheels were set in motion and early on Monday afternoon Sweden, through its Embassy in Moscow, asked the Soviet Union for information on what had happened. The initial response by the Soviet Atomic Energy Authorities was to deny knowledge of any nuclear accident in the Soviet Union (although it was later to emerge — and be confirmed by the Soviet authorities — that an accident had happened, at Chernobyl, at 1.23 am on Saturday 26 April 1986 (see Chapter Seven)).

A day is a long time in politics, and through Monday representations were made to the Soviet Union by a number of countries seeking information. Sweden took the lead. Mrs Birgitta Dahl (Energy Minister) called upon the Russians to inform the rest of the world of nuclear accidents — especially if radiation was likely to spread to other countries — in good time and to improve their nuclear security. Hers was not the only call for all Russian nuclear reactors to be placed under international control. Norway's Environment Minister (Mrs Rakel Surlein) announced the likelihood that representatives would soon be sent to Moscow to lodge a formal complaint about the “regretful” incident at Chernobyl.

Bowing to international pressure, the Soviet Council of Ministers issued a brief statement through the news agency Tass, which was broadcast on Soviet television at 9.00 pm that evening. It was a fairly bald statement which gave a number of facts:

(1) an accident had occurred at the nuclear power plant at Chernobyl, north of Kiev i...