eBook - ePub

Brief Therapy

Myths, Methods, And Metaphors

- 513 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Brief Therapy

Myths, Methods, And Metaphors

About this book

A tapestry of rich and varied perspectives drawn from a remarkable event. The Brief Therapy Congress, sponsored by the Milton H. Erickson Foundation, brought together over 2200 therapists and an impressive faculty that included J. Barber, J. Bergman, S. Budman, G. Cecchin, N. Cummings, S. de Shazer, A. Ellis, M. Goulding, J. Gustafson, J. Haley, C. Lankton, S. Lankton, A. Lazarus, C. Madanes, W. O'Hanlon, P. Papp, E. Polster, E. Rossi, P. Sifneos, H. Strupp, P. Watzlawick, J. Weakland, M. Yapko and many more.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Brief Therapy by Jeffrey K. Zeig, Stephen G. Gilligan, Jeffrey K. Zeig,Stephen G. Gilligan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART V

Techniques of Brief Therapy

CHAPTER 18

Seeding

PREFACE

I will begin by asking you to participate in a learning experiment. Carefully study the following paired associates; e.g., “warm—cold.” Later I will test you: If you are presented the word “warm,” the correct answer, of course, will be “cold.” Here is the list of five paired associates:

1) Red—Green

2) Baby—Cries

3) Light—Name*

4) robin—bird

5) Apple—Glasses

6) Picture—Frame

7) Ocean—Moon

8) Surf—Paper

INTRODUCTION

Milton Erickson discovered numerous creative methods to promote therapeutic change in his hypnotic/strategic approach to psychotherapy. Two of his most famous techniques were the interspersal method (Erickson, 1966) and the confusion technique (Erickson, 1964). These innovations were among his greatest technical contributions to hypnosis and psychotherapy. Another technical advance was his use of “seeding.” Although seeding was a common part of Erickson's hypnosis, psychotherapy, and teaching, this little-understood method has yet to be more fully elaborated. There are no papers or chapters on seeding. No references to the technique are found in Erickson's collected papers (Rossi, 1980) or in the books coauthored with Rossi (Erickson & Rossi, 1979, 1981; Erickson, Rossi, & Rossi, 1976).

The purpose of this chapter is to present and develop the concept of seeding as an integral part of the process of Ericksonian psychotherapy. Seeding did not originate there, however; its analogs are used in literature, social psychology, and experimental psychology. Suggestions and examples are provided so that practitioners from all clinical disciplines can include this technique in their therapeutic armamentarium.

WHAT IS SEEDING?

Seeding can be defined as activating an intended target by presenting an earlier hint. Subsequent responsive behavior is primed by alluding to a goal well in advance (Zeig, 1985a, 1988). By preceding the eventual presentation of a future intervention with a cue, the target (a directive, interpretation, hypnotic trance, etc.) becomes additionally energized. It then is more readily and effectively elicited. Seeding establishes a constructive set from which a future goal can be elicited.

Here is a simple example of seeding: If a therapist knows in advance that he will offer a hypnotized patient a suggestion to slow down his eating, the therapist might simply cue this idea by appreciably slowing down his rhythm of his own speech—perhaps even prior to the hypnotic induction. Also, the therapist can emphasize during an early phase of trance work that one of the real pleasures of hypnosis is the experience of spontaneously slowing down rhythms of movement. These seeded ideas will be subsequently developed. More complex examples of seeding will be presented later.

THE HISTORY OF SEEDING

Jay Haley first introduced the idea of seeding in 1973 in Uncommon Therapy. He pointed out that:

In his hypnotic inductions, Erickson likes to “seed” or establish certain ideas and later build upon them. He will emphasize certain ideas in the beginning of the interchange, so that later if he wants to achieve a certain response, he has already laid the groundwork for that response. Similarly, with families, Erickson will introduce or emphasize certain ideas at the information gathering stage. Later he can build upon those ideas and situations as appropriate. (p. 34)

Zeig (1985b) noted that seeding was one of Erickson's most important and least understood techniques and provided examples of how seeding could facilitate amnesia. Zeig (1985b) emphasized how Erickson was acutely attuned to the process of intervening: “He would not just present an intervention, but would seed the idea well in advance” (p. 333). This use of indirection could elicit a responsive set and build response potential by gradually energizing sufficient associations to the intended intervention so that it would be acted upon once it was offered. Therapy, as Erickson conceived it, was often a process of using indirect techniques to guide associations and build enough positive associations to “drive” constructive behavior (Zeig, 1985c). Zeig (1985b) added, “The importance of this type of priming cannot be overemphasized. Erickson would not only seed specific interventions, he also would seed his stories before presenting them” (p. 333). Additional references to seeding can be found in Zeig (1980, p. 11; 1985a, pp. 38–39; 1987, p. 401; 1988, pp. 366–367).

Steven J. Sherman (1988), a noted social psychologist, described the concept of priming, the term experimental psychologists use for “seeding.” He indicated that “priming refers to the activation or change in accessibility of a concept by an earlier presentation of the same or closely-related concept” (p. 65). Sherman reviewed some of the experimental literature and concluded, “The extent of priming effects is remarkably comprehensive and general. Seeding concepts and ideas can alter what subjects later think about, how they interpret events and how they act. . . . The possible uses of priming techniques for altering clients’ thoughts and behaviors have only begun to be appreciated. Understanding both the techniques for priming concepts, as well as the likely consequences of priming, should be of great value to psychotherapists” (pp. 66–67).

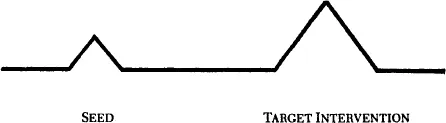

Seeding is a technique that often is effected on the level of preconscious associations. Via an earlier indirect presentation, an association to a target concept is elicited and strengthened. Accessibility of the seeded concept is thereby altered. When the previously implied idea, emotion, or behavior is presented more directly, there is enhanced activation. The arousal provided by seeding can be conscious and dramatic or subtle, working on a level of building preconscious associations. This diagramed timeline of therapy illustrates the process of seeding:

The initial “seed,” which is analogous and/or alludes to the subsequent target intervention, is presented indirecdy. During the time between seeding and intervention, the patient is stimulated into an unconscious search around the idea (or category of ideas) alluded to by the seeded concept. Thus, psychotherapy is woven into a process of moving in directed steps.

PREHYPNOTIC SUGGESTIONS

Seeding can be an integral part of the process of effective psychotherapy. In his initial formulation, Haley (1973) emphasized how therapeutic seeding of ideas ensures continuity: “Something new is introduced but always within a framework that connects it with what was previously done” (p. 34). In outlining the stages of Erickson's utilization approach, Zeig (1985a) described the process of psychotherapy, indicating that interventions should be properly timed and seeded. This methodology was described as SIFT—an acronym standing for (Seed and move in Small Steps), Intervene, and Follow-Through. Target Interventions should be seeded and “braided” together in small steps. “By the time Erickson's main intervention was presented, it was one small step in the chain of steps to which the patient had already agreed” (p. 38).

Sherman (1988) also emphasized that seeding was part of the therapeutic process. “Setting clients up for things to come implies that Erickson was always looking forward and planning ahead. . . . [He] predicated his current behaviors on the basis of what he knew was coming” (p. 67).

In the process of seeding, therapists naturally practice strategic therapy, a form described by Jay Haley (1973) as any therapy in which the therapist is actively involved in determining a specific outcome and individualizing an approach for each problem. By definition, whenever therapists seed an intervention, they are being strategic because they are planning ahead to increase effectiveness.

Seeding also can be conceived of in a slightly different way: It can be considered a “prehypnotic suggestion.” (The concept of “prehypnotic suggestion” is used at the Erickson Foundation's training clinic, The Milton H. Erickson Center for Hypnosis and Psychotherapy, and was introduced by two of our clinicians, William Cabianca and Brent Geary.) Prehypnotic suggestions refer to the class of maneuvers that enhance the acceptance of subsequent directives and injunctions. Because the way in which directives are “packaged” often determines the extent to which the patient accepts them, as part of our training model at the Erickson Center, we teach the concept of “bonding the client with the intervention.” Prehypnotic suggestions allow future directives to be placed in a “fertilized bed” where they can be better accepted. Prehypnotic techniques include using patient values; speaking the patient's experiential language; pacing (meeting the patient at the patient's frame of reference); moving in small strategic steps; the use of therapeutic drama; and the confusion technique (Erickson, 1964). Seeding is one of the most important types of prehypnotic suggestion.

It may seem that prehypnotic suggestions are not worth the effort, yet we have found that, paradoxically, the additional time devoted to prehypnotic maneuvers makes therapy briefer because these maneuvers decrease patient resistance. The words of a popular song echo this philosophy, “You get there faster by taking it slow.”

Seeding is also worth the trouble because, by its very nature, it can elicit drama. When the target intervention is offered, there is increased drama—and arousal—as the previously seeded associations “coalesce.” When patients suddenly realize the relevance of the indirectly seeded precursors, the target is energized.

This dynamic tension helps to make the therapy into a Significant Emotional Event (SEE). Building on the work of Massey (1979), Yapko (1985) has elaborated on how psychotherapy can be “viewed as the artificial or deliberate creation of a SEE in order to alter the patient's value system in a more adaptive direction” (p. 266). Building on this position, I would define psychotherapy as the creator of a SEE, the imperative of which is “By living this (dramatic) experience, therapeutic change will happen.”

Drama is, of course, an important part of literature, and a concept similar to seeding is often a part of good literature.

SEEDING IN LITERATURE

In an earlier work (Zeig, 1985a), I pointed out that “Erickson challenged his students to develop an ability to predict behavior and to use predictions diagnostically as well as therapeutically” (p. 81). I remember the time Erickson (personal communication, 1974) instructed me to read the first page of the novel Nightmare Alley, by William Gresham (1946), and then tell him what was said on the last page. This was an attempt to help me understand how behavior is unconsciously patterned. I didn't understand the point of the exercise when I read the first page, but after I'd read the entire novel, I realized Gresham had seeded the ending in the beginning. This literary technique is called foreshadowing (cf. Zeig, 1988). Examples of foreshadowing can be found throughout literature, in theater, in movies, on television, and even in music, where a musical theme can be alluded to early in the piece and subsequently developed. I think it was the Russian playwright Chekhov who said, “If there is a gun on the mantle in the first act, somebody will get shot by the third act!”

Take, for example, the movie version of Wizard of Oz. In the initial scene, the martinet, Miss Gulch, tries to hurt Dorothy's dog, Toto. When she subsequently confiscates Toto, Dorothy calls her “You wicked old witch.” And, in Oz, Miss Gulch is in fact depicted as a witch.

In the beginning of the movie, we also are introduced to the three farm hands, Auntie Em, and the Professor. The Bumbling Huck tells Dorothy, “You aren't using your head about Miss Gulch. Don't you have any brains? Your head isn't made of straw.” Of course, in Dorothy's subsequent fantasy, Huck is portrayed as the straw man.

The reactive Zeke, who eventually is seen as the timid lion, says when we are first introduced to him, “[Miss Gulch] ain't nothing to be afraid of. Have a little courage, that's all. Walk up to her and spit in her eye.” He is very bold when Miss Gulch is not there.

The emotional Hickory, who eventually becomes the cataleptic tin man, tells Dorothy, “Some day they will erect a statue to me.”

The “Wizard of Oz” is initially presented as Professor Marvel, a good-hearted, but incompetent and grandiose huckster, a presentation that is structurally similar to the Wizard in Dorothy's fantasy.

Dorothy's fantasy also is “seeded” by Auntie Em, who explains, “Find a place where you won't get into trouble.” This starts Dorothy thinking about her special place over the rainbow.

Obviously, the author and script writers went to considerable lengths to foreshadow their story. Their efforts were rewarded by enhanced dramatic and emotional impact.

An analog of foreshadowing has been extensively researched in experimental psychology, where it is known as priming or cueing. Next, I present a brief, but comprehensive, review of the experimental literature in priming.

PRIMING IN EXPERIMENTAL AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY

In experimental psychology, priming is used to study models of memory and learning (Collins & Loftus, 1975; Ratcliff & McKoon, 1988; Richardson-Klavehn & Bjork, 1988) and social influence (e.g., Higgins, Rholes, & Jones, 1975). For example, priming is used to research a “spreading-activation” theory of memory. Collins and Loftus (1975) indicate that when a concept is primed, activatio...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Convocation Speech

- I. Keynote Addresses

- II. Overviews

- III. Family Therapy

- IV. The Temporal Factor in Brief Therapy

- V. Techniques of Brief Therapy

- VI. Models of Brief Therapy

- VII. Distinguishing Features of Brief Therapy

- VIII. Special Concerns

- IX. Mind-Body Healing

- Contributors