![]() Section I

Section I![]()

The Turkic Peoples of Afghanistan

Malcolm Yapp

Numbers and Distribution

Turkic speakers number about ten per cent of the population of Afghanistan and form the third largest language group after the Pashtu and Persian (Dari) speakers. In the late nineteenth century they were thought to represent about half of the population of the northern provinces, but since that time there has been a substantial immigration of Pashtuns into those provinces and it is now doubtful whether Turkic speakers form a majority in any, although they represent a substantial portion of the population in Fariab, Jawzjan, Balkh and Kunduz.

Turkic speakers in Afghanistan inhabit the northern part of the country between the Hindu Kush mountains (and their westerly prolongation) and the Soviet Central Asian frontier. Their numbers can only be roughly estimated for there has been no full census in Afghanistan. They may be divided into four groups.

Uzbeks

The largest group of Turkic speakers is the Uzbeks who live mainly in the provinces of Fariab, Jawzjan, Balkh, Samangan and Kunduz; a few inhabit Takhar. Their number is variously estimated as being between 1 and 1.5 million. They identify themselves by old Uzbek tribal names, for example Haraki, Kamaki and Mangit, although they are generally detribalized. The Uzbeks arrived in the area during the sixteenth century following the Uzbek conquest of Turkestan and until the consolidation of the Afghan state in the mid nineteenth century established a succession of petty chiefdoms throughout the area. They are now predominantly settled farmers.

Turkomans

The second largest group of Turkic speakers in Afghanistan is composed of the Turkomans who inhabit the north-western region of Afghanistan, including the northern parts of the provinces of Herat, Badghis, Fariab and Jawzjan. A colony is also established in Herat city. Their number is estimated between 150,000 and 0.5 million. They employ tribal names. The largest group are Ersari; other tribes include Tekke, Salar, Saryq, Chekra, Mawri, Lakai and Tariq. Some of the Turkomans are the descendants of those long resident in the area, others of refugees from Soviet Turkmenia who entered Afghanistan after 1917. There are marked differences between the two groups. The Turkomans are partly settled and partly nomadic although there is a growing tendency to settle permanently as farmers.

Kirghiz

The Kirghiz inhabit the north-western region and are found in the provinces of Takhar and Badakhshan. Their number is under 100,000 and is probably much smaller than this figure. They are principally nomadic. They appear to have been residents of the area for centuries although some may have arrived as refugees.

Kazakhs

The smallest group of Turkish speakers is the Kazakhs, who live mainly in Badakhshan province and especially in the Wakhan strip. They number only a few thousands and are almost exclusively nomads. Many arrived as refugees from Russian and Chinese Kazakh areas.

In addition to these Turkic speakers three groups of Persian speakers should also be mentioned, the Aimaqs, Hazaras and Qizilbash. The Aimaqs are a nomadic or semi-nomadic tribe of north-western Afghanistan who are thought to have a Turkic or partly Turkic origin. Their language contains a large number of Turkic words. The Hazaras are a largely settled Shi’ite Muslim group from Central Afghanistan who are often supposed to be descended from soldiers (presumably Mongol or Turkic) who accompanied the Mongol invasions. The Qizilbash are a group which inhabits part of Kabul; they represent the descendants of the garrison established during the Persian occupation and drawn from the Turkic tribes which formed the main support of the Safavid state in Iran.

Civil and Economic Status

Turkic speakers are full citizens of Afghanistan with the same rights and duties as other citizens. Turkic, however, is not an official language and therefore was not employed in schools, courts or local government before 1978. Turks therefore were at a disadvantage as compared with the speakers of Persian and Pashtu in securing government employment. It has also been alleged that they were discriminated against on political grounds.

The Turkic-speaking peoples make a major contribution to the economy of Afghanistan. Most of the cotton and sugar-beet is grown in their lands, which are also the centre of the Qaraqul and hand-woven carpet industries. Natural gas is also produced in the Shibarghan area and some light industry has become established in the northern region. In particular the Uzbeks have taken advantage of economic opportunities to develop commercial interests and move into Kabul as traders as well as members of the professional class. By far the greatest part of Afghanistan’s export earnings derives from the products of the Turkic region.

Language, Education and the Media

The Turkic speakers of Afghanistan are mainly illiterate; literacy rates for the provinces which contain the Turks average around 3 per cent. The Turkic languages are written in a modified Arabic alphabet. Until the 1978 revolution there was no publication in the Turkish languages. The revolutionary government announced a policy of developing the minority languages and especially of producing school text-books in the Turkic languages. It is unclear what progress may have been made in this endeavour. Various dialects of Turkic are spoken; considerable differences exist between them but it is said that they are mutually intelligible.

Religion and Culture

Like 90 per cent of Afghans, the Turkic speakers of Afghanistan are Sunni Muslims of the Hanifi school.

In the absence of publications in Turkic languages it is difficult to say much about cultural life. The Central Asian epics are known: the Kirghiz epic Manas, the Uzbek and Chagatay epics and the Mongol epic Geser exist in various forms. Matters relating to horses figure prominently in Turkic life, the favourite sport being buzkashi which resembles polo.

London, 1989

Notes

This chapter was written in 1980. Amid the confusion of the revolution, the Soviet invasion and the civil war in Afghanistan it is difficult to be precise about changes which have taken place since then, but the following features are worthy of note. First, the Turkic speaking areas appear to have suffered less during the violence of the civil war than have other regions. Although Turkic speakers have figured both in the ranks of the supporters of the regime and among the resistance they appear to have been less conspicuous on either side than other nationalities.

Second, there has been an outflow of those Pashtuns who settled in the area since the late nineteenth century, many of them becoming refugees in Pakistan or in Kabul. The major Turkic groups, notably the Uzbeks and Turkomans, have remained in their locations, although Kazakhs of Wakhan emigrated to Pakistan at an early stage of the revolution and were subsequently resettled in Turkey. As a consequence Badakhshan is more Tajik than it was formerly and the main Turkic-speaking provinces more Turkic. Although the civil war in Afghanistan has featured two ideologies—Marxism and Islam—which are supra-national in character, the war has inflamed national differences and fostered the concentration of nationalities in different regions.

Third, the promises of the revolutionary regime do appear to have been carried out in some degree and the use of Turkic languages in schools and publications has been permitted. It is difficult to be sure of the extent of this development as the only source of information is government publications.

Fourth, as a consequence of the Soviet presence, the greatly increased traffic across the frontier with the USSR and the negotiation of bilateral co-operation agreements with Soviet republics, contacts between the Turkicspeaking peoples of northern Afghanistan and the Turkic peoples of the USSR seem to have increased.

Bibliography

(a) Official Sources

Area Handbook for Afghanistan, fourth edition (US Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., 1973).

(b) Other Sources

Adamec, Ludwig W. (ed.), Historical and Political Gazeteer of Afghanistan, vol. 1: Badakhsh province and north-eastern Afghanistan; vol 4: Mazar-i Sharif and north central Afghanistan (Graz. Akedemische Druck u.Verlagsanstalt, 1972, 1979).

Dupree, Louis, Afghanistan (Princeton University Press, 1973).

Jarring, G., ‘On the distribution of Turk tribes in Afghanistan: an attempt at a preliminary classification’, Lunds Universi tets Arsskri tt, N.F. Ard I, 35, 44, Lund, 1939.

Shahrani, M. Nazif Mohib, The Kirghiz and Wakhi of Afghanistan (Seattle and London, University of Washington Press, 1979).

For Further Bibliographical Details See:

McLachlan, Keith and Whittaker, William (eds.), A bibliography of Afghanistan (Wisbech, Middle East and North African Studies Press, 1983).

![]()

The Turkic Peoples of Bulgaria

Firoze Yasemee

Historical Background

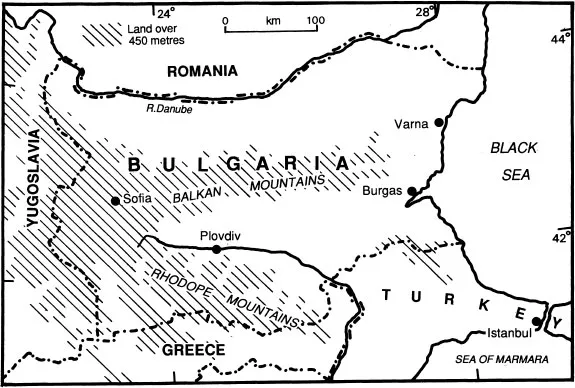

Although the Bulgars who crossed into the Balkan Peninsula from the steppes of Southern Russia in the seventh century AD were a Turkic people, they were rapidly assimilated by surrounding Slav populations, and the modern nation which bears their name is Slavic in all significant points of cultural tradition and identity. Bulgarian is a Slavic language, akin to Russian and Serbo-Croatian, and the Bulgarians’ traditional faith is Orthodox Christianity. A significant Turkish presence in Bulgaria goes back no further than the Ottoman conquest, which took place at the end of the fourteenth century. The conquest was followed by a substantial settlement of Anatolian Turks in the towns and in the countryside, and the Turkish population was further swelled by a limited assimilation of indigenous elements, with conversion to Islam leading to Turkification. Nonetheless, despite the establishment of considerable local majorities, the Turks remained a minority of the overall population throughout the Ottoman period.

Ottoman rule lasted for five centuries until, in 1878, Bulgaria was awarded her de facto independence by the treaties of San Stefano and Berlin. Formal independence of Ottoman suzerainty came in 1908. Bulgaria gained further Ottoman territory in the Balkan Wars of 1912–3, but in these same conflicts, and in the subsequent First World War, she was obliged to cede territory, some of it with substantial Turkish populations, to Greece, Serbia and Rumania. In 1940 Bulgaria regained the southern Dobrudzha, with its substantial Turkish population, from Romania, and since then her frontiers have undergone no permanent change. Since 1944 Bulgaria has been ruled by the Fatherland Front, a coalition dominated by the Bulgarian Communist Party, and under Communist direction Bulgarian society has been thoroughly remodelled on orthodox Soviet lines. The People’s Republic of Bulgaria maintains close ties with the Soviet Union, and is a member of the Warsaw Pact and of Comecon.

With the ending of direct Ottoman rule in 1878, the Turks lost their dominant social and political position within Bulgaria and became a subordinate minority in a state ruled by Christian Bulgarians. Many emigrated., but many, perhaps 750,000, remain to this day. In addition to these ancestors of the Ottoman Turks, Bulgaria contains two other Turkic-speaking minorities: about 6,000 Tatars, whose descendants entered the country from the Black Sea steppes, and a somewhat smaller number of Gagauz, Christian Turks whose presence predates the Ottoman conquest. The Turks of Bulgaria, like those of Turkey, are orthodox Sunni Muslims. This faith is shared by other groups in Bulgaria, chief among whom are the ‘Bulgaro-Muhammedans’ or Pomaks, who number approximately 160,000 and inhabit the Rodop mountains: they are of Bulgarian speech. About half the country’s 200,000 Gypsies profess Islam, as do the Tatars.

In recent decades it has become increasingly difficult to assess the state of Bulgaria’s Turkish population. Since the late 1950s, the Bulgarian authorities have maintained considerable reticence on the subject of all national minorities, and Macedonians, Pomaks, Gypsies, Tatars and—most recently—Turks have been subjected to official pressures to assimilate themselves to the Bulgarian majority. Minorities are no longer identified in published statistics and are but rarely mentioned in books and periodicals. Reliable and up-to-date information regarding their numbers, conditions...