![]()

Part I

National Identities

![]()

1 Making Sister Julie

The Origin of First World War French Nursing Heroines in Franco-Prussian War Stories

Margaret H. Darrow

In the fall of 1914, Sister Julie of Gerbéviller became a media heroine. According to the many press accounts and interviews, this sixty-one-year-old nun had confronted the invading German army and defeated it. The French press had begun to report her activities in early September; the story spread quickly, her exploits multiplying in each new iteration. Originally commended for her courage in nursing under bombardment, newspapers soon credited her with saving Gerbéviller from destruction and wounded French soldiers from massacre.1 While some images transformed her into a slender young woman, many journalists delighted in describing her short, stout, pugnacious person: “her eyes sparkling, her whole face expressing kindness,” “comely and fresh as an apple,” “a tough, little, resourceful … countrywoman, full of goodness and practicality.” “Lacking very scientific methods, [she] poured out the balm of her spirit, what her good sense told her was best to do.” Everyone’s granny and, according to Maurice Barrès, “all this enhanced by spirituality.” “A soldier, in fact,” a soldier “for God and for France.”2

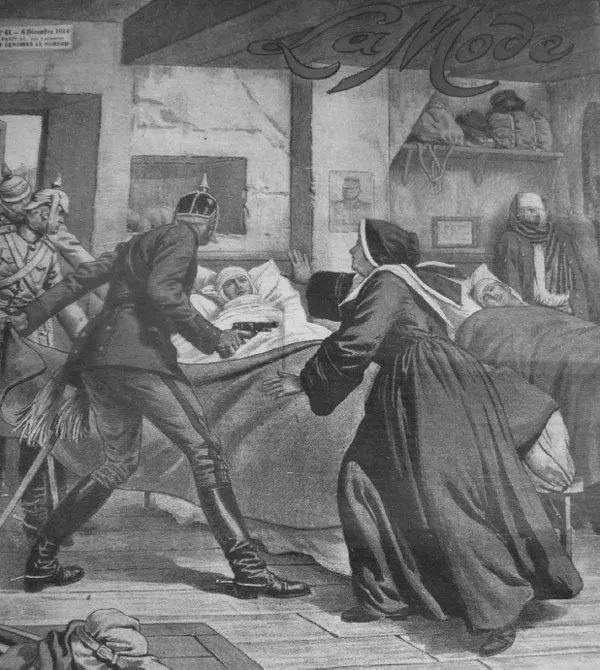

The France that Sister Julie embodied was not invaded and occupied but triumphant. Although accounts praised her nursing and her care for the poor and the refugees, the core of her story was the confrontation and defeat of the German invaders. Later versions of her tale multiplied the confrontations; British journalist White Williams, who interviewed her in 1915, related five separate incidents in which Sister Julie routed the Germans.3 The confrontation most frequently recounted, and also illustrated (see Figure 1.1), occurred over the bodies of wounded French soldiers for whom she was caring. In early accounts, the German commander merely wanted to make them prisoners; in later ones, murder was his intent. In a 1917 interview, Sister Julie asserted that the officer had had a dagger hidden in his breast and his finger on the trigger of his pistol, meaning “to harm our poor little wounded.” Pantomiming both parts in the confrontation, “she raises the poignard of the German Colonel; you see it held over her head ready to strike.” Then she mimed throwing herself across the bed of a wounded soldier, saving his life and those of all the wounded. The vignette concluded with the German officer’s capitulation—“Madame, you are brave; no one will harm you.”4

Figure 1.1 The cover of La Mode (6 December 1914). Sister Julie confronting the German menace, 24 August 1914. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

In the first months of the war, Sister Julie was the best-known French nurse. But neither her actions nor her image derived from the Red Cross, the main source of French nurses during the war. In fact, Sister Julie, her person, and her actions, were nearly antithetical to the image of women’s wartime nursing that the French Red Cross worked to convey: secular, professionally trained, under the authority of a male doctor, in an auxiliary hospital far from combat. Instead, Sister Julie’s story rested on earlier models of French women’s contributions to war. Although these models had antecedents in the Napoleonic Wars and even earlier, reports of French women’s nursing in the Franco-Prussian War had recently updated and popularized them. Nursing stories from the Franco-Prussian War not only shaped the press reports of Sister Julie; they also influenced French women’s response to the outbreak of war in 1914.

The role of the French Red Cross in the Franco-Prussian War, and the stories it inspired, was complicated, even conflicted. This was the first war in which the French Red Cross, founded in 1866, had participated.5 On the one hand, it gained the young organization publicity and respect; on the other, the war revealed the organization’s inadequacy. The latter view came to dominate in the two decades before 1914 as rival branches of the French Red Cross competed for members, money, and official recognition. The first French organization of the Red Cross, the Society to Aid the Military Wounded (Société de secours aux blessés militaires or SSBM),6 was small, elitist, and all male. In the few years prior to the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War its leadership hosted an international conference and organized an exhibit at the Exposition Universelle of 1867 but did little to expand the organization beyond the imperial court circle or prepare for practical wartime intervention. The outbreak of war in July 1870 found the SSMB with only three functioning branches and little in the way of medical staff, materials, or funds. Nonetheless, it quickly organized and dispatched sixteen ambulances from Paris to the front. Once Paris was besieged, the SSMB continued operations from the provinces, setting up and supplying emergency aid posts and hospitals as the German armies swept through northern and central France.7

During and immediately after the war, the SSMB received much praise for its efforts, but it quickly relapsed into inactivity. Two new Red Cross organizations—the Association des Dames françaises (ADF), founded in 1879 for women, and the Union des Femmes de France (UFF), founded in 1881 by women—revitalized the French Red Cross and gave it a new direction.8 Unlike the SSBM, these societies recruited and trained women for wartime nursing. They also vigorously lobbied the government and the military to include Red Cross volunteers in war planning.9 In pursuing these goals, the ADF and the UFF reconfigured the meaning of volunteer nursing in the Franco-Prussian War. According to their spokespeople and literature, French women’s response to the war in 1870 had been seriously inadequate—good-hearted but wrongheaded—and, in their lack of preparation, nearly as responsible for the French defeat as was the French army. Dr. Auguste Duchaussoy, founder of the ADF, wrote in a manual for nurses’ training in 1881 that the “bitter memory of our lack of foresight” in 1870 showed “that the best promptings of the heart cannot replace technical knowledge.” Dr. Pierre Bouloumié, speaking at a UFF conference, maintained, “We must have the courage to say that not everyone did her duty, all her duty, in 1870, and that is precisely because no one was prepared.”10 The SSMB in the Franco-Prussian War was blameworthy rather than praiseworthy, its story a cautionary tale to inspire the government, the army, and French women to do better, much better, in the future.11 And to do better, everyone must support the French women’s Red Cross organizations.

The story of volunteer nursing efforts during the Franco-Prussian War, as crafted by the ADF and the UFF, emphasized women’s lack of preparation for the war, particularly in contrast to the German Red Cross.12 Their promoters applauded the outpouring of French women’s charity in 1870 but at the same time denigrated its efficacy. Their favorite word to describe these volunteers was “improvised”:

At the moment of terrible awakening, everything had to be created, improvised. While the men sought to remedy the disastrous consequences of their culpable negligence, women throughout the whole land met in committees as soon as the war began, to organize everything that was needed, improvising tents, beds, bandages, medicine … It is not easy to create an administration, to improvise facilities and all this in the midst of a terrible crisis like the one then taking place in France.13

Such a situation should not occur again. As journalist Maxime Du Camp wrote in his three-part article on the Red Cross in La Revue des deux mondes: “Never again should we be caught unprepared by events, as we were in July 1870, having to organize in the midst of battle, in the face of the enemy.”14

In their 1912 book, La Femme sur le champ de bataille, Dr. Arnaud and Dr. Bonnette divided women’s wartime nursing into two types, the “improvised nurses” of the past and the professionally trained volunteers that they advocated for the future: “By improvised nurses we mean women whom wartime chance has abruptly placed before the wounded or ill, and who display all the treasures of charity and devotion until then hidden in their nature.”15 Ste Hélène, Paulette Bonaparte, Sisters of Charity, “society ladies and bourgeoisies,” cantinières,16 and actresses, Dr. Arnaud and Dr. Bonnette described them all in the same terms: their hearts were in the right place but they were untrained and unorganized. Modern warfare demanded more than Christian charity, noblesse oblige, and maternal instinct. “In modern wars we no longer find the nun or the cantinière, as in the past, stooping to ease or bandage the wounded. These different feminine types have both disappeared.” They were replaced, the authors asserted, by the “vocational nurse,” scientifically trained and professionally experienced: “we mean the French Red Cross.”17 At this point, the book reveals its true character: a recruiting tract for the Red Cross. Dr. Arnaud and Dr. Bonnette exhort French women to prepare now for their future wartime duty.

Other Red Cross promoters went further in their criticism of volunteer nursing in the Franco-Prussian War and in their recipes for improvement. Dr. Eifer, an ADF supporter, ridiculed the much-publicized hospital that the Comédie Française had set up in 1870 as amateurish and even frivolous: “You don’t improvise a nurse any more than you improvise an actress; each career requires a long apprenticeship,” he claimed.18 The appropriate model, according to Maxime Du Camp, was the army; just as soldiers trained in anticipation of war, so should volunteer nurses. “In a country where the armies are permanent and always in a state of readiness, the societies responsible for medical services must be similarly permanent.”19

Among the variety of improvised nurses that Red Cross promoters denigrated were most of the volunteer nurses of the Franco-Prussian War. While the historic examples that Arnaud and Bonnette cited, like Ste Hélène, were scarcely rivals to the contemporary Red Cross, the Franco-Prussian War nurses were, and although they would be overshadowed and forgotten in the Red Cross’s triumph in the First World War, their stories were quite familiar to French women in the years prior to 1914. In fact only the cantinière had truly disappeared, discontinued by the French army in 1905.20 Stories of the others—Sisters of Charity, society ladies, bourgeoisies, and actresses—continued to inspire French women in 1914. These stories also served as models for press reports about nurses in the early months of the First World War.

Arnaud and Bonnette’s 1912 list of improvised, outmoded nurses echoed the categories that publicists had developed not to denigrate but to celebrate French women’s patriotism during the Franco-Prussian War. Paul and Henry de Trailles’s compendium, Les Femmes de France pendant la guerre et les deux sièges de Paris, published in 1872, includes chapters titled “The Sister of Charity,” “The Actress,” “The Cantinière,” and “The Society Lady,” as well as “The Ambulance Nurse.”21 This variety really boiled down to two sorts of activity. Ladies and actresses created, administered, and nursed in auxiliary hospitals; cantinières and ambulance nurses tended the wounded on or near the battlefield. Sisters of Charity could figure in either role.

As early as 19 July 1870, the day war was declared, La Petite Presse reported, under the title “Women under the Colors!”, that “a certain number of ladies request authorization to follow the troops in the eventuality of war, to lavish their care in the ambulances.” A week later the paper reported, “The number of ladies who ask to go to the ambulances is greater and greater … in fact, we have heard there are now nearly a thousand such requests.”22 All were directed to the Red Cross, but the SSBM limited women’s contribution to collecting money and bed linen and making bandages. The society’s president, the comte de Flavigny, dismissed such requests, implying that these women only wanted to follow their husbands or lovers.23

In mid-August reports appeared of a n...