![]()

1 Social context

The purpose of this chapter is to present the historical, political and economic contexts of the sociolinguistic research as relevant to the data on Hebrew borrowings in Palestinian Arabic analysed in the following chapters. It is asserted that these selected aspects of the context bear on Palestinian linguistic practices by the medium of an articulation with ideologies that are socially developed to deal with the context. Additionally, the context forms the environment in which this particular study took place, and so affected how the research question was framed and how the data was collected. The facets of the context that will be treated here in brief are: the history of Palestine refugees and the current social makeup of the refugee camps where the fieldwork was located; Palestinian migrant work in Israel; and imprisonment of Palestinian political activists. An interpretation of gender relations in Palestinian society will be integrated in the discussion of each topic. Academic works on these subjects will be supplemented by reports from non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and by observations from personal experience of living in the region.

1.1 Palestinian refugee history

Approximately 4.8 million refugees from pre-1948 Palestine and their descendants are registered with the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). They live in refugee camps and towns in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Lebanon, Syria and Jordan. Their status is deemed temporary until an agreement is reached regarding a permanent resolution to their situation. How the situation came about is a controversy that has filled many volumes of academic historiographical writing (Morris 1987; Khalidi 1992; Pappé 2006).

When the UN General Assembly voted on 29 November 1947 for the partition of Palestine, which was under British Mandate administration, into Jewish and Arab states with an international zone around Jerusalem, Jewish organisations including paramilitary formations took it as a signal to establish positions in what was to be their future state. Palestinians staged demonstrations and acts of violence. As the British Mandate retreated from its administrative and policing responsibilities, Jewish groups advanced, in the absence of any organised equivalent on the Palestinian side. From April 1948, amid news of killings of Palestinian civilians by the Jewish paramilitaries, the exit of the Palestinian population started: some were forcibly displaced while others left, temporarily they thought, to reach safety in the hope that Arab armies would push back the Jewish conquest of their lands. Indeed, the armies of the neighbouring Arab states, themselves newly independent from French and British control, crossed the borders after the British Mandate was terminated on 14 May 1948. This, the first Arab–Israeli war ended with armistices signed during 1949, the terms of which gave the state of Israel 78 per cent of the territory of Mandate Palestine. The stumps of what was supposed to have been the Arab state according to the UN Partition Plan – the West Bank and the Gaza Strip – went to Jordan and Egypt, and of the 900,000 or so Palestinians who had formed the majority of the population in the territory that became the state of Israel, 150,000 received Israeli citizenship, and were placed under military law. Approximately 750,000 were registered with UNRWA when the agency started operations in 1950. Refugee status as registered with UNRWA is inherited through patrilineal descent (Blome Jacobsen 2004).

The first controversy relating to this course of events is the Israeli denial of responsibility for the problem, and the erasure of any visual evidence that the dispossession and displacement of Palestinians happened. A widespread fiction in Israel would have it that the Palestinian refugee camps actually house Arabs from neighbouring countries who had tried to enter Israel, attracted by its economic possibilities, but were rebuffed. Recreational parks were planted on the ruins of Palestinian villages as the landscape was re-sculptured, and the history of the places is unknown to present-day Israelis. The settling of the refugee issue has been a stumbling block in negotiations between the PLO and Israeli governments. In Israel, acknowledging responsibility is seen as a first step towards a resolution that would involve the repatriation of Palestinians; that, because of the Israeli concern for preserving a Jewish majority, would supposedly lead to the destruction of Israel (Masalha 2003). It is against the backdrop of this denial, and of the physical erasure of Palestinian villages and place names inside Israel, that Palestinians put an emphasis on reiterating the refugees’ narrative.

The second controversy relates to the Palestinian insistence on the ‘inalienable’ right of return for Palestine refugees. Aside from international law, which stipulates the right of individuals and their descendants to return to their country with which they have close and enduring connections (Amnesty International 2001), the Palestinians invoke the right of return as a central tenet of their nationhood. Beyond the legal or political positions, the refugees’ plight has formed the narrative of Palestinian identity. Baruch Kimmerling and Joel Migdal (1993: 208) posit that the refugees, the most disadvantaged social group, provided the cultural meaning of what it meant to be Palestinian ‘from below’, after three decades of the British Mandate during which Palestinian leaders formulated Palestinian identity ‘from above’. This radicalised the Palestinian polity whose leaders from old notable families had to catch up or be obsolete, replaced by modern actors in paramilitary and political groups. Refugee camps, though socially and economically depressed, are still seen as the motors of Palestinian politics: in this sense they are not marginal. In turn, this translates into official insistence on the right of return, though anathema to the Israeli side. The refugees who remember 1948 are the embodiment of this element of the national narrative, which is referred to as the ‘Nakba’, or catastrophe. This is transmitted through the generations, and also, the successive generations of refugees identify with the village of origin.

1.2 Shuafat refugee camp

Shuafat refugee camp is unique among all the Palestinian refugee camps in that it lies within territory officially governed by Israel: in the Jerusalem municipal area – East Jerusalem – annexed by Israel in 1967 after the war that saw the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights and the Sinai occupied by the Israeli army. The annexation is not recognised by any state apart from Israel itself. This gives the residents of the camp entitlement to a rare and prized document: the blue ID card, which confers residency in Jerusalem. This does not equate to full citizenship, but gives some of its advantages: primarily, movement within Jerusalem, both East and West, access to Israel and the West Bank and the claim to some social services, for instance, subsidised health care. On the other hand, all of Palestinian East Jerusalem is subject to hostile planning policies which favour Israeli settlement but constrain Palestinian development (Bimkom 2005). This has resulted in serious problems for the camp, which suffers from poor sanitation, irregular water supplies and hazardous overcrowding.

Approximately 11,000 people are registered as refugee residents of Shuafat camp (UNRWA 2011b). However, estimates as to the total camp population vary from twice to three times that number. The reason for this is that Shuafat refugee camp functions as a ‘no-go zone’ where the Jerusalem police rarely enter, but nevertheless qualifies as Jerusalem residence. Because the Jerusalem Municipality is enforcing ever-stricter regulations for retaining the blue ID card, card-holders have to prove continuous residency in the municipal area, which suffers from extraordinary housing shortages in the Palestinian sector. The housing restrictions are not implemented in Shuafat camp, which means there are no house demolitions which are the bane of other Palestinian neighbourhoods, and so its 0.2 sq. km have become prime real estate. Six-or eight-floor buildings are built on foundations that are meant for one or two floors, and many non-refugee Jerusalemites have moved in despite the poor conditions, to preserve their title to the precious ID card. Such are the paradoxical consequences of the Israeli authorities’ efforts to limit the Palestinian presence in Jerusalem.

The land for the camp and its water and sanitation systems were supplied by the Jordanian state when the camp was established in 1966, but when the Israeli authorities took over they required payment for the water bills. The refugees refused to pay and in the 1980s the water supply was discontinued. Camp youths connected the camp water supply to a mains pipe leading to a neighbouring Israeli settlement and established an unofficial source. Since then, these unofficial connections supply the camp until they are discovered and closed by the Israeli authorities, at which point a new one is created. This has become more difficult since the Israeli army built the fence and wall which encloses Palestinian areas in the West Bank. This fence and wall encircles Shuafat refugee camp from three sides, leaving one road open leading to the east, towards the West Bank, and one gate to the west, leading to the rest of Jerusalem, guarded by a military checkpoint. Only holders of blue ID cards can pass that checkpoint. On 25 November 2008 the Israeli Supreme Court rejected a petition by camp residents for the re-routing of the wall so that Shuafat refugee camp would remain within East Jerusalem in the annexed municipal area. In 2004 the International Court of Justice had given the advisory opinion that the route of the Israeli fence and wall was illegal because it cut though Palestinian territories (ICJ 2004).

Education, basic health services and waste management in the camp are provided by UNRWA. Other projects are run, or at least approved by, the Popular Committee for Services, a PLO body that exists in every Palestinian refugee camp with varying degrees of efficiency and corruption. The Committee comprises representatives from every PLO faction (which excludes Hamas and Islamic Jihad) and from large clans. A modicum of order is supposed to be enforced in the camp by the Committee, which is headed by the Fatah party, using factional and familial networks to impose discipline. This system has seemingly broken down in Shuafat refugee camp. For example, during my time in the camp, the Committee issued an edict that stalls, including a pirate gas station, selling their wares in the street on the main crossroads, would be banned. The stall holders did not comply with the edict, and one night several vegetable stalls were torched. It was presumed that the arson was perpetrated by a gang linked to the Committee. Several days later the head of the Committee was stabbed by a member of a clan whose vegetable stall had been burnt down. After that, the pirate gas station was set on fire, causing a blast that brought down a nearby electricity pylon and cut the power supply to the camp. As I approached the blackened gas station in the morning, I found some of my English pupils scavenging for scrap metal and excitedly discussing what sweets they would buy with the money they would get in exchange for the metal. A new electricity pylon was built within two days by engineers hired by Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas’s office (of Fatah, of course). Everyone I knew denied having any suspicions regarding the identity or affiliations of the perpetrators of the arson attack on the gas station. It was safer not to name any possible suspects: the tit-for-tat attacks could continue and spread, and it was best to stay clear.

This anarchy is tolerated by the Israeli authorities in the midst of the Jerusalem Municipality. The status of ‘no-go zone’, unpoliced, cut off from Jerusalem by the wall and checkpoint but administratively part of Jerusalem, accessible from the West Bank but not under the jurisdiction of West Bank authorities, makes it a breeding ground for crime including drug smuggling, according to camp respondents. The rampant poverty combined with access to Israeli state benefits has created dependency on social welfare including unemployment benefits and child benefits. Domestic violence is widespread, according to camp respondents. Since the Israeli police will not enter the camp, and the Palestinian police based in Palestinian Authority–administered areas must not enter because it is in annexed Jerusalem, the battered women have no state authority to turn to. One woman I visited said that her husband had a West Bank ID card and lived in the West Bank with another wife, but came to the camp each month when she picked up her social benefits cheque. If she didn’t give it to him, he beat her. I was told this was an extreme example of a common story.

I chose to base part of my study in Shuafat refugee camp because the Jerusalem residency ‘blue ID cards’ give workers from the camp easier access to jobs in Israel than their West Bank counterparts with ‘green IDs’. Indeed, aside for employment in UNRWA schools and some of the other camp services, such as the rehabilitation clinic where I made contacts, or the nurseries, and the local bus company, most of the available jobs were outside the camp in the Israeli sector.

1.3 Dheisheh refugee camp

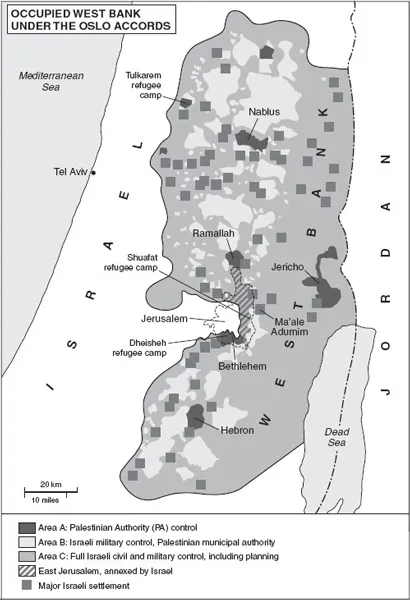

Dheisheh refugee camp lies to the south of Bethlehem within Area A, under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority (PA). Areas A, B and C are administrative divisions that emerged from the Oslo negotiations. Under its provisions, Area A, which includes Palestinian built-up areas in the West Bank (excluding Jerusalem), is under PA jurisdiction for both civilian matters and policing. In Area B, which comprises most of the agricultural lands around Palestinian villages, the PA is responsible for civilian affairs and the Israeli army deals with policing. In Area C, which amounts to over 60 per cent of the West Bank (excluding Jerusalem), Israel is responsible for both law enforcement and civilian affairs of Palestinians, and for the Israeli settlements. Areas A and B are not contiguous (see Figure 1.1 for the different areas). The camp lies on one side of the main road from Bethlehem to Hebron. The shops that lie on the main road are frequented by people from Bethlehem who are not refugees, and so the camp is integrated into the economy of the town. Refugees who could afford to do so have moved out of the camp into homes on the other side of the main road, in a new neighbourhood called Doha. This has alleviated the overcrowding that plagues other refugee camps. Up to 13,000 people are registered as refugees with Dheisheh’s UNRWA office. Not all live in the camp but they can use UNRWA facilities such as schools, which are chronically short of places.

Figure 1.1 The West Bank, Occupied Palestinian Territories. The map shows the approximate location of the three refugee camps where the sociolinguistic fieldwork took place. © Amnesty International; refugee camps added. Map based on a Foundation for Middle East Peace Map by Jan de Jong.

The running of the camp is relatively autonomous from the PA, thanks to an active Popular Committee for Services. Historically, the composition of the Committee in Dheisheh has favoured avowedly left-wing parties, mainly the Palestinian Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), which still has a strong base there but is losing ground to Islamist parties, as elsewhere among Palestinians. The PFLP activists in the camp credit the smooth running of the camp to its influence. The party, for instance, set up literacy clubs and political discussion groups in the 1980s. In the mid-1990s, party activists opened a sports and cultural centre in the camp which also attracts foreign volunteers to run activity clubs for children. The Committee acts as a mediator between the camp residents and the PA or other authorities. It can use its credibility as a democratic body and its legitimacy as the authoritative voice of refugees (with its resonance in the Palestinian national credo) to obtain special benefits. If that doesn’t work, the political factions do not hesitate to resort to demonstrations.

Incidents involving arson will exemplify how the camp is organised in contrast to the anarchy that prevails in Shuafat refugee camp. The Palestinian mobile phone company Jawwal built a transmitter tower near the camp in 2006. After reading articles linking proximity to such towers with a rise in cases of cancer, members of the Committee asked Jawwal to dismantle the tower and move it farther from the camp. When the company refused to do so, camp residents set fire to it. Another example involves the provision of water, which was historically supplied free of charge, as with all refugee camps. When economist Salam Fayyad’s government decided to collect payments for the water bills in the second half of 2007, the camp residents refused and blocked the main Bethlehem–Hebron road with burning tires until the free water supply was restored. Such demonstrations are seen by Palestinians as manifestations of the refugees’ hardiness that has enabled them to overcome the tribulations that have beset them. Introducing oneself in Bethlehem as min il-muxayyam, ‘from the camp’, elicits respect.

The closure of the Occupied Palestinian Territories, enforced increasingly since the 1990s with checkpoints, restricted allocations of permits, and the building of the fence and wall through the West Bank, has disproportionately affected employment rates in Dheisheh refugee camp (for an analysis of reasons for refugees suffering more from the closures than other Palestinian workers, see section 1.5). UNRWA estimates that the unemployment rate in Dheisheh refugee camp stands at 30 per cent (UNRWA 2011a). Strong social solidarity organised through political parties and the safety net provided by UNRWA prevents residents from becoming destitute. Some manual labourers who used to work in Israel now work in local Palestinian quarries, where the wages are much lower than what they would have earned in Israel in the past. The years of investment in women’s education have also paid off as some now work in administrative jobs in the PA or as professionals in the medical and educational sectors (Blome Jacobsen 2004).

1.4 Tulkarem refugee camp

With over 18,000 registered refugees, Tulkarem refugee camp is the second most populous camp in the West Bank. It lies within the municipality of Tulkarem town, in the northwest of the West Bank near the Green Line, which is the 1949 armistice line between Israel and what was then Jordan. Like Dheisheh, it is officially under the jurisdiction of the PA. Politically, it has been a bastion of Fatah and many young men from Tulkarem refugee camp were recruited into Fatah’s armed units known as the Tanzim, or Alaqsa Martyrs Brigade, during the Second Intifada, which started in September 2000. Islamist paramilitary groups also gained ground in the camp. This led to crushing reprisals by the Israeli army, as a result of which many men in the camp were killed ...