![]()

Part I

Europeanization Travels to the Western Balkans

![]()

1 | Europeanization Travels to the Western Balkans |

| | Enlargement Strategy, Domestic Obstacles and Diverging Reforms |

| | Arolda Elbasani |

Introduction

During the 1990s, the Western Balkans1 have dominated academic attention as a region of violent conflicts and delayed transitions when compared to the smooth and peaceful transformations elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). However, the region’s reputation as Europe’s ‘trouble-making periphery’ promised to change at the turn of the 2000s, when the European Union (EU) expanded its concept of enlargement to include all Balkan countries left out of the previous wave of enlargement. The EU’s ‘unequivocal support for the European perspective of the Western Balkans’ (European Council 2003), coupled with a regiontailored enlargement policy – the Stabilization and Association Process (SAP) – (Elbasani 2008; Noutcheva 2012) were widely promoted as the anchor of future reforms. By that time, EU enlargement was held as a success story that contributed to creating peace and stability, inspiring reforms, and consolidating common principles of liberty, democracy as well as market economies, in the previous candidate countries in the East. Meanwhile, the Western Balkans, for their part, had moved away from the open conflicts and exclusionary nationalist politics that kept hostage their first decade of post-communist transformations (Vachudová 2003). More mature politicians, reformists and committed Europeanists in particular, have gained strength in government and society, creating a friendlier environment for the EU-led reform agenda (Pond 2006). The EU policy shift towards the region, on the one hand, and increasing domestic demand for integration, on the other, have generated high expectations that enlargement strategy will work to discipline democratic institution-building and foster post-communist reforms in the same way that it did in the previous candidates in CEE.

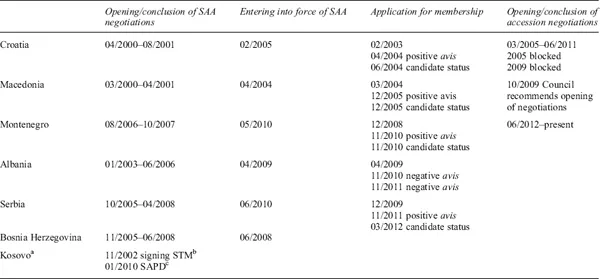

By 2013, European membership had emerged as the cornerstone of the region’s future, all target countries having advanced up the institutional ladder envisaged by the SAP (see Table 1.1). Stabilization and Association Agreements (SAAs, the equivalent of European Agreements) are now signed with all Western Balkan countries except Kosovo. All countries, except Bosnia and Kosovo, have applied for membership, which opens the path to the final stage of negotiating accession terms. Macedonia and Serbia are granted full candidate status and are now waiting to start accession negotiations. Montenegro started negotiations in June 2012. Croatia meanwhile is held as the exemplary model that has made the big jump to conclude accession negotiations in 2011, and can look forward to assuming full membership in 2013. The EU has also advanced trade relations with all Western Balkan countries via the adoption of autonomous trade measures and the early implementation of SAA trade provisions. Aid has continued to flow under the new Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA), which is explicitly geared towards bringing institutional reforms into line with the EU standards. Even Kosovo, which is not recognized by all the EU members, is accommodated in the enlargement process through custom-made mechanisms and procedures.

Table 1.1 Status of relations between the EU and Western Balkan countries

Source: European Commission (2011a).

Notes

a The contractual relations between the EU and Kosovo are based on different instruments designed by the Commission in the context of non-recognition of Kosovo.

b The Stabilization and Association Process Tracking Mechanism (STM) is a mirror mechanism of SAP to monitor and keep under control reform processes.

c Signing of Stabilization and Association Process Dialogue (SAPD), which is a custom-made mechanism for Kosovo that mirrors SAAs in terms of sectors included and negotiating dialogue.

The enlargement strategy is centred on the principle of conditionally – the rewards offered by the EU (most importantly financial assistance and membership) are conditional on the Western Balkan states meeting demands set by the EU. The basis of the EU demands, which reflect general democratic norms and more specific standards developed at the EU level, is outlined in the initial Copenhagen Criteria, different regional approaches, and SAP conditionality (Pippan 2004). Moreover, each consecutive stage of SAP comes with an increasing load of conditions that the countries need to comply with in order to advance to the next stages and towards the goal of membership. More recent rules on the accession process have enhanced the strategy of conditionality to the extent they suggest application of ‘strict conditionality at all stages of negotiation’ (Council of Europe 2007).

Given the embedment of the Western Balkans in the EU enlargement processes, Europeanization (a short-hand for the domestic influence of the EU) has emerged as the dominant approach to the study of EU-led reforms across the region. Similar to the previous wave of enlargement in CEE, research on the Western Balkans has made enlargement conditionality the central focus of analyzing the role of the EU (Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier 2006: 88). After all, both regions share the main features that have arguably animated the celebrated success of the EU conditionality in CEE, most importantly the substantial rewards underpinning the EU demands and the strategy of reinforcement by reward (ibid.). However, in contrast to the previous CEE candidates, most Western Balkan countries consist of borderline cases of transformation or ‘deficient democratizers’ that face unfavourable domestic conditions and share a poor record of reforms. Yet, very little research is done on whether and how the challenging factors on the domestic side might undermine the transformative power of the EU in the same way they have delayed and refracted region’s trajectory of post-communist transformation. Europeanization studies looking at the domestic side of the equation are still at an early stage, lacking conceptual detail and comparative evidence on the array of domestic factors that challenge the role of the EU in difficult cases of democratization (Sedelmeier 2011: 30; Brusis 2005a: 23). Empirical research on Europeanization in the Western Balkans, on the other hand, remains largely within the realm of expectations and has yet to consider the domestic factors that set those countries apart and their implications for the presumed impact of Europe (Pond 2006).

This volume brings domestic factors back in, and analyze the transformative power of the EU against challenging domestic factors in the Western Balkans. Conceptually, we differentiate the array of domestic factors that characterize deficient democratizers across agency-and structural-based categories. In the Balkan context particularly, we distinguish limited stateness as ‘deep structures’ that constrain the capacity of human action to take on and execute the EU rules, and thus limit the scope of elite-led Europeanization. We suggest that stateness is the missing link between the transformative power of the EU and the scant willingness and capacities to fully adopt the EU rules across the Balkans. Yet, we maintain that structural constraints, including problems of stateness, are parameters, which the domestic agency will have to confront and cope with, rather than insurmountable obstacles, in the course of difficult Europeanization.

We use controlled comparisons among different national cases and issue areas to investigate the EU and domestic triggers of the Europeanization outcomes. The empirical chapters take into account the categories of domestic factors outlined in this introductory chapter, but necessarily approach these factors from various angles, depending on the particulars of the country and issue being analyzed. In this way, the empirical chapters can speak to a common research agenda, but also bring in more case-based idiosyncratic factors and contextualise the path of Europeanization taken in different countries. The task of the empirical chapters is to identify the appropriate blend and the intensity of the EU strategy, domestic choices and state constraints that render intelligible the process of Europeanization in a given country and area of reform.

Our approach has both intellectual advantages and limitations. In-depth case studies necessarily bring in various issues that do not always permit neat comparisons and straightforward explanations. Unpacking the box of domestic politics in difficult cases of democratization in the Western Balkans is also a complex venture into different layers of post-communist, post-authoritarian and post-conflict challenges. The value of our enterprise is to conceptualize and assess the ‘weight’ of domestic conditions that might inhibit Europeanization at the receiving end of enlargement. Our framework bridges Europeanization studies, comparative democratization as well as post-communist and Balkans area studies, which have so far largely developed as separate areas of research and rarely speak to each other. In addition, it provides a theoretically informed comparative assessment of similarities and differences of paths of Europeanization across different countries and areas of reform in the Western Balkan region.

The remainder of this chapter is divided into four parts. First, we sketch a Europeanization approach to the post-communist transformations and distinguish between different strands of explanations. Second, we unpack the domestic factors that might challenge the role of the EU at the receiving end of enlargement in the Western Balkans. The third part discusses the book’s approach towards assessing the role of EU enlargement. The fourth part provides an overview of the chapters and findings.

Europeanization via Enlargement and Post-communist Transformation

The process of EU enlargement is largely credited with having supported post-communist reforms in the candidate countries in the East, with democratization being faster and less prone to reversals in countries sharing a strong promise of membership (Pop-Eleches 2007a: 142). Indeed, enlargement policy is often credited with the quick, coinciding and, to some degree, convergent reforms in CEE countries which were included in the first wave of Eastern enlargement concluded in 2005, with Romania and Bulgaria succeeding in 2007 (Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier 2006).

Analytically, the Europeanization perspective on post-communist transformation draws on the large literature that analyzes the impact of the EU on member states’ polity, politics and policies. The focus here is to connect European and domestic politics by shifting attention from the European-level orientation of classic integration theories to the domestic level of change (Vink and Graziano 2008: 4). The research agenda also goes beyond a narrow notion of ‘impact’ by absorbing concerns of both institutionalization, i.e. the development of formal and informal rules, procedures, norms and practices; and complex modes of interaction between the EU and domestic level, instead of a unidirectional impact of Europe (Vink and Graziano 2008: 17).

Empirically, Europeanization via enlargement extends the scope of research to include the distinctive ways in which the EU affects post-communist applicant countries. The EU’s relations with its candidates are different from those with its member states, and so are the instruments at its disposal, especially the pressure of conditionality. In addition, during the Eastern enlargement, the EU has developed a range of tools that enable and complement its policy of conditionality – prescription of required reforms, aid and technical support, systematic monitoring, political dialogue, benchmarking between different candidates and the gate-keeping of accession according to a candidate’s demonstrated progress (Grabbe 2003: 312–16). Besides, candidate countries coming from state socialism became subject to Europeanization while undergoing large-scale regime change involving the installation of new democratic and market economy rules, and, sometimes, even the creation of new states (Dimitrova 2004). This did not only prove to be an immense process of transformation, but it also meant that multiple reforms had to advance together in a rough balance in order to prevent general failure. A Europeanization perspective to post-communist change should, therefore, analyze the influence of the EU at the intersection of the EU enlargement pressure and the scope and challenge of post-communist transformation.

Top-down EU Conditionality Versus Contextualized Domestic Influences

Increasing evidence on uneven reforms across post-communist countries that were subject to similar EU enlargement policies has contributed to shift Europeanization research towards problematizing and qualifying the role of the EU vis-á-vis other sources of differentiated domestic change. However, the literature remains divided when it comes to prioritizing the EU-or domestic-level factors and assessing the magnitude of change that can be attributed to the EU enlargement policies.

The dominant strand of Europeanization research attaches an overwhelming role to EU enlargement strategy, especially the top-down policy of conditionality, when explaining the scope of domestic change (Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier 2005a). In the context of CEE, the EU has made accession of new candidates contingent on a set of intrusive criteria that were first outlined at the Copenhagen Council in 1993, and were then operationalized in more detail and expanded further in the so-called Copenhagen documents (Kochenov 2004). These conditions come with sizable rewards for post-communist elites, especially the highly appreciated ‘carrot’ of membership, which the EU bestows on compliant countries and withholds from non-compliant ones. Candidate countries have no voice in the making of the rules that regulate their advance in the accession process. The asymmetrical power that the EU holds in this process, when combined with the high volume and intrusiveness of the rules attached to membership, have led to a top-down process of rule transfers, and it has arguably allowed the Union unprecedented influence on the restructuring of domestic institutions and the entire range of public policies in CEE (Pridham 2005; Kubicek 2003). That these conditions have been, at least partially, designed to address transformation problems and overlapped with on-going post-communist modernization (Goetz 2001a: 1037) have increased their appeal to post-communist reformers. The EU’s top-down enlargement strategy has arguably proven so powerful that ‘Europeanization superseded the transition, Westernisation, or globalisation of CEE … as the dominant motor of institutional change’ (Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier 2006: 99).

An alternative strand of research, usually grounded in assumptions of comparative politics and post-communist area studies, adopts a more sceptical view of the EU strategy and its influence on post-communist transitions. Critics of the EU, and other external factors more generally, share the concern that it is important not to ‘overestimate the EU influence’ (Grabbe 2003: 305) and/or ‘prejudge the role of the EU vis-á-vis other sources of domestic change’ (Goetz 2000). This is often the case with classic research on candidate countries’ Europeanization, which takes EU conditionality as a guiding analytical concept and then evaluates the results of reform as measured against the EU prescriptions (Brusis 2005b: 297; Elbasani 2009a: 7–8). The de-contextualized and short-term reform assessments thus attained are particularly predisposed to decouple the policy output from the evolutionary domestic process and the array of domestic factors that screen, download and implement the EU requirements. In addition, assumptions on the causal relation between top-down EU pressure and domestic change run into trouble against accumulated findings that enlargement has generated differential impact across different countries, issue-areas and time periods (Börzel and Risse 2009). Critical accounts of candidate countries’ Europeanization, therefore, call for the need to contextualize the impact of the EU strategy and bring in more prominently domestic factors as the key to explaining successful rule transfers in the post-communist space (Vachudová 2005; Jacoby 2004; Hughes et al. 2004; Noutcheva 2012).

Thus, the ‘domestic turn’ in Europeanization research has encouraged deeper introspection into the conditions that facilitate the role of the EU in various national settings. Linkages with post-communist area studies have proven especially helpful in drawing attention to the variety of ‘domestic conduits’ that do the heavy lifting to transmit the EU demands into the domestic arena. Yet, Europeanization research in general tends to focus on different aspects of the EU strategy, while relatively little attention is paid to the domestic politics category, which is neither conceptually specified nor systematically explored (Sedelmeier 2011: 30).

Unpacking Domestic Contexts and Challenging Factors in the Balkans

This section relies on both Europeanization research and post-communist and Balkan area studies to specify the array of domestic factors that characterize deficient democratizers in the Western Balkans. In line with much of the Europeanization research, we distinguish (1) the strength of reformist elites, or potential EU allies, as the primary conduits of successful EU transfers at the receiving end of enlargement (Jacoby 2006; Sedelmeier 2011). In the Balkan context, we also identify (2) hindering historical legacies and (3) weak stateness as interrelated long-term structures or ‘deep conditions’ that shape, if not determine, the range of possible elite choices, and might hence limit the scope of agency-driven Europeanization (Parrot 1997; Pridham 2000; Diamandourous and Larrabe 2000). These factors should not be seen as insuperable obstacles, but indeed as parameters, which human agency, whether in the form of individual leaders, elites, or collective social actors, will have to confront and cope with in the course of Europeanization, seeking to minimize their restraining impact and to maximise its freedom to craft new arrangements conducive to successful Europeanization.

The Strength of EU Domestic Allies

Europeanists’ search for domestic conduits of change has, by and large, focused on the arrays of domestic actors with whom the EU can create some kind of ‘coalition’ to push forward its programme of reforms (Jacoby 2006: 625; Sedelmeier 2011: 14). Accordingly, the EU’s conditional rewards appeal to the circle of domestic reformist and/or liberal groups who share the preferences of the EU; but repel groups who resist the EU enlargement agenda. Thus, the EU strategy works where and when reformist constellations, which tend to ally with the EU, get sufficiently empowered to pursue the EU requirements (Schimmelfennig 2007). In these cases, the EU rewards tip the domestic balance in favour of reform via (1) strengthening domestic groups who want much the same as the EU, (2) expanding the number and variety of the EU’s allies, and/or (3) weakening or neutralizing opponents whose interests are hurt.

The EU strategy of reinforcing domestic allies can encounter far more resistance where the break with the past was rather ambiguous, and the old apparatchiks continued to hold key positions in post-communist politics and governing structures, such as in t...