- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1954, this is the first full-length account of the history of the Working Men's College in St.Pancras, London. One hundred and fifty years on from its foundation in 1854, it is the oldest adult educational institute in the country. Self-governing and self-financing, it is a rich part of London's social history. The college stands out as a distinctive monument of the voluntary social service founded by the Victorians, unchanged in all its essentials yet adapting itself to the demands of each generation of students and finding voluntary and unpaid teachers to continue its tradition.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of the Working Men's College by J F C Harrison in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education General1854

II. Foundation

‘We came forward to help the working men that we might help ourselves.’—F. D. MAURICE: Working Men’s College Magazine, 1859.

‘We opened our College on October 31st. The admissions are about 130. The Arithmetic and Algebra, Geometry, Grammar, and Drawing Glasses are the most popular . . .’—F. D. MAURICE: MS. letter, 14 November 1854.

I. Principles and Purposes

IN later years Maurice traced the origins of the College back to the series of Bible readings begun in 1848 at his house. ‘It began’, he said in the Annual Report for 1866, ‘from a Bible Class.’ But the first mention of anything educationally more ambitious than this or the night school in Little Ormond Yard, seems to have come from Charles Mansfield, one of the four original founders, along with Maurice, Ludlow, and Kingsley, of Christian Socialism. For in November 1852 Ludlow wrote to him: ‘I wish you were with us, to work out your own idea of a Working Men’s College.’ The origin of this idea was probably the educational work of the Promoters, which had been started at the Hall of Association a few months earlier.

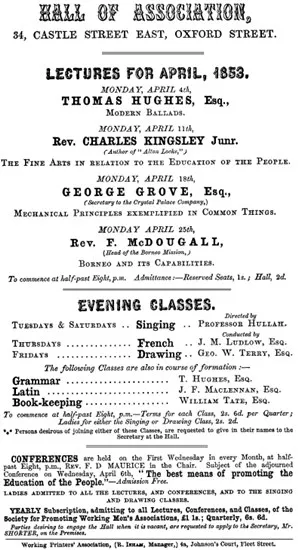

The Hall of Association had been constructed by the North London Working Builders (one of the working associations) to the design of F. C. Penrose, a Promoter, in the spring of 1852, and was situated at the workshops of the Working Tailors’ Association at 34 Castle Street. It became henceforth the headquarters of the movement, and was used in particular for the holding of conferences and lectures on co-operation. In March 1852 a series of fortnightly lectures and debates, organized by a committee with Shorter as secretary, was begun. The speakers included national figures in Chartist and radical reform circles, and attracted a large attendance. This encouraged further efforts in the same direction, and in November a series of lectures and classes was advertised. The management of these efforts was in the hands of a Committee of Teaching and Publication, consisting of some fourteen of the Promoters (including Maurice, Ludlow, and Westlake), with Shorter as secretary. The lectures advertised in the November–December programme covered a wide variety of subjects: Maurice on ‘The Historical Plays of Shakespeare’, Walter Cooper on ‘The Life and Genius of Burns’, and John Hullah (professor of vocal music at King’s College, London, and the initiator of a widely adopted method of music teaching) on Vocal Music. Other lectures were on Proverbs, Rivers, Photography, Entomology, Popular Astronomy, and ‘Architecture and its Influence, especially with reference to the Working Classes’; the lecturers all being Christian Socialists. In addition, classes in Grammar (under Hughes and Vansittart), English History (under Maurice and Neale), French (under Ludlow), Book-keeping, Singing, Drawing, and Political Economy were projected; and the Bible Classes which had hitherto been held at Maurice’s house were now transferred to the Hall. In the following year additional lecturers were brought in, including Kingsley, Llewelyn Davies, and Lloyd Jones. The fees were 2d. per lecture, and 2s. 6d. per quarter for the classes. Although intended primarily for the associates, no attempt was made to restrict either the lectures or classes to members of the working associations, and women were admitted equally with men. These lectures and classes continued throughout 1853, and 1854 until the very eve of the launching of the College; and even after that certain of the activities of the College, notably the Adult School, continued to be held in the Hall. As Ludlow said in a talk in 1894, the Working Men’s College ‘was only a development of classes held throughout 1853 at the Hall of Association in Castle Street’.

Handbill advertising lectures and classes at the Hall of Association, 1853

Nevertheless, no amount of lectures and classes will in themselves ever develop into a College. True, an interest in education and especially university education, had characterized the work and publications (for example, in the very first number of the Christian Socialist) of the Christian Socialists from their commencement; they had also heard from Lloyd Jones about the success of the recent People’s College at Sheffield: and Ludlow and Mansfield had toyed with the idea of a College as early as 1852. But before all these elements could interact and cause a change in substance a catalyst was required. In the autumn of 1853 this was provided—in the form of Maurice’s expulsion from his Professorship at King’s College, London. To Maurice this was not unexpected; his Christian Socialist views had long given offence to members of the Council of King’s College; throughout 1850 and 1851 the influential Quarterly Review had attacked both his theological teaching and his socialism; and Jelf, the Principal of the College, saw a connection between his championship of Christian Socialism and his unorthodox theological views. The occasion of the crisis was the publication by Maurice of a volume of Theological Essays, and the doctrine which gave offence was that in his last essay, ‘On Eternal Life and Eternal Death’—an essay whose unorthodox views on the doctrine of endless punishment had come largely out of his recent experiences with and sympathies for working men. The diplomatic handling of the affair by the Principal and by the Bishop of London afforded Maurice the opportunity of quietly withdrawing had he wished. But he refused any easy way out; and hence in November he was expelled.

Expressions of sympathy from his students and friends now came to Maurice in several forms: and one of them was in the form of an Address from the working men of London, presented to him at a meeting in the Hall of Association on 27 December 1853. The document was signed by a committee of the leading members of the working associations, including Charles Allen and William Newton of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, Walter Cooper, Robert Curtis, Thomas Shorter, and others who shortly afterwards became the earliest students at the College. Then followed the names of 953 working men, employed in 95 different trades. Several speeches were made at the meeting, and in one of them the hope was expressed that Maurice ‘might not find it a fall to cease to be a Professor at King’s College and to become the Principal of a Working Men’s College’. To a man like Maurice such an invitation sounded as no less than a call from God—‘there seemed to me a manifestly Divine direction towards it in all our previous studies and pursuits’. To Ludlow it was clear that on the 27 December 1853 the Working Men’s College had been spiritually founded.

By 10 January 1854 Maurice was already writing to Kingsley of ‘my college’, and said that the proposal had been ‘kindly received in many quarters, but it requires careful consideration and the exclusion of all big-wigs’. The next day the decisive move was made. The Minute Book of the Council of Promoters of Working Men’s Associations records that at a meeting on 11th January,

‘A conversation took place concerning the establishment of a People’s College in London, in connection with the Associations, and Mr. Vansittart Neale read a letter received from Mr. Wilson, the Secretary of the People’s College, Sheffield, as to its origin and history, and also the five Annual Reports of that Institution.’

And as a result,

‘The following Resolution, proposed by Mr. Hughes, seconded by Mr. Lloyd Jones, was carried, “That it be referred to the Committee of Teaching and Publication to frame, and so far as they think fit, to carry out, a plan for the establishment of a People’s College in connection with the Metropolitan Associations”.’

The Committee of Teaching and Publication held several meetings, agreed on certain principles, and asked Maurice to draw up a scheme embodying these. On 7 February 1854 he submitted this to the Council, who adopted it with only minor modifications; and a circular was then issued setting forth the main points of the proposal. Maurice’s plan was printed as a small twelve-page pamphlet entitled Scheme of a College for Working Men, and is of great significance as being the earliest detailed proposal for the College. Above all, the principles upon which the College was to be based, and by which its whole future was to be governed, were here clearly laid down. Maurice was greatly concerned with the need for sound and clear principles right from the beginning. The proposed experiment, he said later in the year, ‘will be good for nothing if it is pursued ever so zealously but not in conformity with sound principles’. In a great many subsequent writings and lectures Maurice was to expound at considerable length the aims and purposes of the College; but in none of them did he surpass, in clarity and succinctness, this first statement.

His starting point was the series of six maxims which the Committee of Teaching and Publication had agreed should be the basis for any plan to be laid before the Council. The primary aim of the College was to be the provision of human studies:

‘They agreed that our position as members of a society which affirms the operations of trade and industry to be under a moral law—a law concerning the relations of men to each other, obliges us to regard social, political, or to use a more general phrase, human studies as the primary part of our education.’

Although it was to be hoped that members of the working associations would enter largely into the scheme, it was not to be restricted to them, but was to be open to adult (i.e. over 16) working men generally. The education provided was to be ‘regular and organic, not taking the form of mere miscellaneous lectures, or even of classes not related to each other’. And the teachers and students together were to form a self-governed and self-supporting organic body, ‘so that the name of college should be at least as applicable to our institution as to University College or to King’s College’.

Maurice himself, in interpreting these views, was prepared to go even further than this. Not only should the proposed college be as much a college as University College or King’s College,

‘I would add, that I think we ought to aim at being much more of a college, in the strictest sense of the word, than either of these bodies, or than any one in Oxford or Cambridge. I do not mean that we shall ever have a Gothic chapel or hall, or endowments, or that we should wish for them. But I mean that, starting from a common maxim and a common object, there ought to be an understanding between us, even when the subjects which we teach are most different . . . that is not found, so far as I know, among professors or tutors elsewhere.’

It was his hope that this new experiment would approximate even more nearly to his ideal of a college than the existing colleges of Oxford and Cambridge; and it is therefore appropriate to consider further exactly what he meant by this term. His son has described how greatly thè name college attracted him.

‘It seemed to him to imply an association of men as men—an association not formed for some commercial purpose and not limited by coincidence of opinion, and to represent, therefore, that union which he was always striving to bring about.’

The word symbolized for him the spirit of a corporate life, of fellowship, of brotherhood in the deepest, Christian, sense. To working men he put the matter in this way when appealing to them in the first Circular of 1854:

‘The name College is an old and venerable one. It implies a Society for fellow work, a Society of which teachers and learners are equally members, a Society in which men are not held together by the bond of buying and selling, a Society in which they meet not as belonging to a class or a caste, but as having a common life which God has given them and which He will cultivate in them.’

It was in this that the Working Men’s College marked a break with all earlier adult educational efforts; it was a far cry from the Mechanics’ Institutes with their science for artisans, and Lord Brougham’s appeals to them to get knowledge that they might get on. The idea of a college was the product of a fusion of two operative ideals in Maurice’s life, the spirit of Christian brotherhood (which had underlain all his Christian Socialism) and the humanist tradition of the older Universities—both of which had been lacking from earlier efforts in the field of education for working men. The form which the new venture assumed, namely that of a college, was not a mere organizational convenience; it was determined by the philosophy of the Founders, in particular by that of Maurice. The idea of a college was thus central to the whole undertaking; all else followed, either directly or indirectly, from this. The emphasis on liberal as opposed to technical studies, the need for humility in the adult teacher arising out of the realization that such education was a reciprocal process, the need to adapt the teaching to the special requirements of working men in order to speak to their condition, the development of a strong social life in the College—these and other characteristics which came to be an integral part of the life and work of the College arose out of or developed in relation to this central idea. The finest ‘College men’ both students and teachers throughout the past hundred years have been those who grasped this idea most fully. The greatness of George Tansley was in a large measure simply this, that he understood more deeply, and applied to his own life more fully than almost any other student or teacher of his day, Maurice’s idea of a College. From such men, and particularly from a small band of devoted adherents in the very early days, there developed, with a speed equalled by no other similar body, a strong College tradition. To an outsider, one of the most marked characteristics of the College is still this very strong corporate loyalty, a devotion to an alma mater reminiscent only of that of an older Oxford or Cambridge graduate for the College in which, as a young man, he spent the most impressionable years of his life. The creation and steady maintenance, despite several periods of very low water, of such a tradition, is unparalleled in the field of adult education; and is a remarkable testimony to the strength of Maurice’s ideal of a College, and the extent to which it was translated into a living reality.

The studies which Maurice recommended for the new College he divided into three categories, Theology, Humanities, and the ‘Natural Division’. He felt that if politics and history were to be brought in, as he thought they ought, there was no escaping the need for religious teaching. In teaching the physical sciences the problem did not arise; but

‘Once bring in politics and history, and you are encountered at every turn by questions which cannot be passed over, and upon which if you speak with any distinctness, you must intrude upon religious, even ecclesiastical ground’.

This was a problem that the Mechanics’ Institutes had met with a rigid ban on politics and theology. But Maurice realized that this was precisely one of the reasons why the Institutes had failed to attract working men; they wished to discuss these problems; it was no use saying to them, Have a class on chemistry instead, for their all too effective reply was to stay away. If, however, classes on history and politics were provided, the problem could not be avoided merely by omitting theology from the list of studies, since the questions requiring a theological answer would still crop up in the classes, and the teachers would then be suspected, rightly, of trickery. The only honest recourse was therefore to offer instruction in theology. Such classes ‘must occupy a prominent place in our course’, but they were on no account to be made a test of admission to other classes. A Bible class was to be held every Sunday evening; but attendance was to be entirely optional. The proposed Humanity course was to consist of Politics, Ethics, and Language; and closely linked with these were to be History and Literature. The Natural Division included Physiology, Machinery, Arithmetic, Drawing, and Music. The exact grouping of these subjects is an unfamiliar one today, and in the event the first classes at the College did not conform to this pattern. The working men were not so interested in politics, and a good deal more interested in mathematics, than Maurice had supposed. The truth is that he was still thinking in terms of Associationism, of devising some means by which ‘the Associations may become guilds of intelligent and thoughtful men, able to exert an immense practical influence upon the whole land’; and he regarded the teaching of history, ethics and theology as ‘better preaching in support of association than any other which we could set on foot’.

This emphasis on the primacy of the liberal studies and the idea of a college were Maurice’s attempt to meet what he considered to be the educational needs of working men at this time. To satisfy these wants in the classroom a special approach would be required—

‘I am strongly convinced that an education of the most ignorant adult must have a different starting point from the education of the most clever boy.’

Obvious as this truth may seem, its neglect has contributed to the failure of many an adult class, both before and since. What Maurice saw so clearly was the all-important truth that the adult student, while he often lacks the trained mind of the clever schoolboy or undergraduate, possesses something which, in its very nature, they cannot have, namely, experience of life. And this experience is particularly necessary for a study of the Humanities, which are essentially ‘adult’ subjects, in that their full significance cannot be ‘learned’, but can only be appreciated as a result of experience of the world. The adult student ‘will find it very hard to get up the facts of history or to learn a language, things which the boy finds easy’. But he has a general knowledge of public affairs, an awareness of right and wrong, experience of suffering and sickness, a highly developed skill with his tools, and the responsibilities of family life around him.

‘These are our data. To neglect these, and lay down a mere scheme of instruction, framed upon the notion of beginning at the beginning or proceeding from first elements to more advanced knowledge is, I conceive, to set aside the order of God’s providence, and to cut off almost all chance of the old scholar ever becoming aware of his ignorance, and so a wise man.’

The technique of adult teaching is therefore to begin with the working man as he is; to accept his limitations, to start from his interests, and to work thence to wider fields.

This statement of method in adult work could scarcely be bettered, and coupled with the idea of a college for the cultivation of liberal studies, augured well for the new venture. The principles here enunciated, however, were necessarily only briefly stated, and details of organization were only touched on lightly. But in June and July 1854 Maurice expanded them in a series of public lectures in Willis’s Rooms, designed to arouse interest in, and if possible secure support for, the scheme. These lectures were subsequently published, under the title Learning and Working;7 and together with the pamphlet, Scheme of a College for Working Men, provide a comprehensive statement of the principles upon which the College was founded. Learning and Working, indeed, is a classic in the literature of adult education; and, in this field, is comparable with that contemporary classic of university education, J. H. Newman’s Idea of a University.

Maurice would have agreed with Newman’s central proposition ‘that all Knowledge is a whole and the separate Sciences parts of one’, and with his further claim that Theology provided the unifying bond between them—‘in a word, Religious Truth is not only a portion, but a condition of general knowledge’. The sense of Wholeness and Unity was dominant in Maurice’s religious thought; as Professor Raven puts it, ‘This was Maurice’s secret, that he saw life whole and saw it in the light of Christ.’ In his educational thought this found expression in his concept of Freedom and Order—

‘. . . the ends which we should propose to ourselves in the Education of working men, and of all men, are to give them Fr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- I Origins, 1848–1854

- II Foundation, 1854

- III Early Days, 1854–1872

- IV Crisis and Reorganization, 1872–1883

- V George Tansley and the College Studies, 1883–1902

- VI The Problems of Middle-age, 1902–1918

- VII The Inter-War Years, 1918–1939

- VIII The Latest Phase, 1939–1954

- Appendix Principals And Vice-Principals Of The Working Men's College, 1854–1954

- Notes and References

- Bibliographical Note

- Index of Persons

- Index of Subjects and Places