- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lull & Bruno

About this book

First published in 1999.This is Volume VIII of ten of the selected works of Frances A. Yates. The studies reprinted here demonstrate not only the range of Frances A. Yate's learning but her determination to go to the root of a problem. In order to understand the thought of Giordano Bruno, Dame Frances found it necessary to investigate the role of Lullism in the Renaissance and this led her back three centuries to the origins of the Art of Ramon Lull.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Essays on the Art of Ramon Lull

Introduction

IN ABOUT 1949 I began to work on what I hoped would be a book on Giordano Bruno, making abstracts of his Latin works. In these I found many references to Ramon Lull, and resolved that I must investigate Lull before going further with Bruno. On the advice of Ivo Salzinger in the first volume of his edition of Lull’s Latin works, the famous Mainz edition of 1721–42, I began with Lull’s Tractatus novus de astronomia. It seemed perfectly unintelligible. There were many circles and other diagrams, labelled with letters of the alphabet. One learned that BCDEFGHIK stood for the Dignities, or Attributes of God, Bonitas, Magnitudo, Eternitas, Potestas, Sapientia, Voluntas, Virtus, Veritas, Gloria (Goodness, Magnitude, Eternity, Power, Wisdom, Will, Strength, Truth, Glory). Most of these divine attributes, or Names of God, were familiar from the Bible. Was the book, then, some kind of pious meditation, turning the Divine Names on the prayer wheels of the Art of Ramon Lull? All Lull’s immensely complex Arts have one procedure in common: they revolve BCDEFGHIK (or sometimes sixteen letters) on circles or wheels.

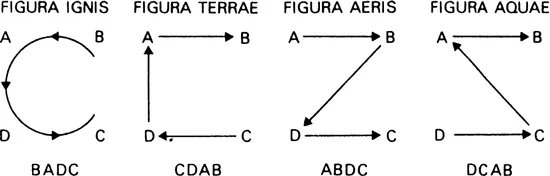

There are other letters, of, apparently, equally serious importance, the letters ABCD, to be used somehow in combination with B to K. With endless repetition the reader is informed that these represent the four elements: Aer (Air), Ignis (Fire), Terra (Earth), Aqua (Water). There must therefore be some kind of cosmological meaning in the Art, though it was difficult to understand how the Elements were supposed to work in connection with the Attributes.

Finally, most baffling of all. Why was the work entitled ‘A New Treatise on Astronomy’?

I struggled with these problems in the articles here reprinted, the writing of which was the hardest task I have ever undertaken. The severe ordeal of battling with Ramon Lull may be reflected in a certain rigidity in the style of the articles.

Both articles are concerned with what I have called Lull’s Elemental Theory. The first article begins by abstracting and examining the elemental theory, from the Tractatus novus de astronomia, and then goes on to prove that the theory underlies all Lull’s work. He believed that he had found a way of calculating from the fundamental patterns of nature, an Art which could be applied, by analogy, to all the arts and sciences. We can calculate the workings of virtues and vices by analogy, with the elemental pattern and its system of devictio. The logical square of opposition is shown to have the same pattern as the square of the concords and contrasts of the elements. Lull believed that he is doing in the Art a ‘natural’ logic, a fundamental logic based on reality. Through this, and through the elemental analogies, he can do all arts and sciences by the Art; he can ascend the ladder of being and understand the nature of God. Finally, and this was its most important aspect in his eyes, by the Art he can convert Jews and Moslems by proving to them the truth of the Christian Trinity.

Lull was a tremendous system-builder. He built his systems, so he believed, on the elemental patterns of nature, combined with the divine patterns formed by the Dignities, or divine attributes as they revolved on the combinatory wheels. For the Lullian Art is always an Ars combinatoria. It is not static, but constantly moves the concepts with which it is concerned into varying combinations.

I was not satisfied with the first article, for it left unsolved a basic problem about the Lullian art. How do the divine Dignities, Bonitas, Magnitudo and the rest, the attributes of God with which Lull begins each Art – how do they connect with the elemental theory? Whence did Lull derive his conviction that these Dignities are directly connected with the Elements and with the stars – the seven planets and the twelve signs of the zodiac – whence they descend through all creation? A source for such ideas was missing.

One day when reading an article by Marie-Thérèse d’Alverny on Le cosmos symbolique du douzième siècle I saw the miniature which is used to illustrate the second article (Pl. 16). The miniature is an illustration in a twelfth-century work the author of which is presenting the system of the universe set forth by the ninth-century Irishman John Scotus Erigena in his extraordinary work De divisione naturae. Scorns sees the whole of nature as proceeding from what he calls the primordial causes, named as Bonitas and other divine attributes. The Scotist primordial causes are creative. They pour their creative power into chaos, a first stage of creation in which the elemental essences emerge as intermediaries between the Creator and His creation.

This is what we see in the miniature with its crude personifications of the Causes, and its schematic attempt to present their creative power through the intermediary of the elements.

I was electrified when I saw this miniature, which is immediately translatable into Lullian terms. There are his Dignities as creative primordial causes, immediately in contact with his Elements as intermediaries between the divine Causes and creation.

The second article here reprinted deals with the influence of the philosophy of Scotus Erigena on the Art of Ramon Lull. There was an interval of five years between the publication of the two articles, which therefore did not make a joint impact. In the first article I saw the basic importance of Dignities and Elements for Lull’s thought, but I did not know that his Dignities were creative primordial causes, and his Elements the first effect of their creative power. This explains the prime importance of the Elemental Figures in Lull’s Art.

The Elements, in their various manifestations on every level of creation, are fundamental forces on all these levels. Lull groups the stars – the seven planets and the twelve signs of the zodiac – in accordance with their elemental affinities and labels them A, B, C or D. Lull can claim that his Tractatus de astronomia is not astrological in the ordinary sense. I have called it ‘elemental astrology’, calculating astral influences through abstracting the elemental affinities in signs and planets. In this way the astrological images are avoided, their influences expressed through abstract letters. Lull’s Art tends to total abstraction. The Divine Dignities are reduced to BCDEFGHIK, and the semi-divine Elements proceeding from them to ABCD.

There has been much speculation among Lull scholars concerning the variation in the number of Dignities on which Lull bases his Arts. Sometimes he uses a sixteen form, in which seven more letters are added to the nine of B to K. I think that the reason for such variations should be sought, not in a supposed historical development in Lull’s mind, but in the Scotist mysticism in which it is possible to build different ‘theories’, or mystical meditations, on varying numbers of Causes. Lull is not a philosophical thinker. He does not develop. The patterns of his mind and art were given to him once and for all in his vision.

These patterns can be expressed in geometrical terms. The Arts were based on three geometrical figures, the Triangle, the Circle, and the Square, and these figures are implicit in the arrangement of the Elements in the Elemental Figures (Figure 1).

Figure 1 (after a drawing by R. W. Yates)

In the thirteenth century, the age of the rise of scholasticism, Lull and his Art provide a channel through which another tradition runs through the scholastic age, medieval Platonism, particularly in forms descending from Scotus Erigena, in which there is some similarity to Cabalist ways of thinking. Erigena’s philosophy of expansion and retraction has more in common with dynamic Cabalism than with purely static Platonism. Lull himself was almost certainly influenced by Cabala which developed in Spain at about the same time as his Art. In fact, the Art is perhaps best understood as a medieval form of Christian Cabala.

When first published the two articles here reprinted were pioneer studies. The cosmological basis of the Lullian Art had been forgotten for centuries; its resemblances to the Scotist system had not been recognized. These new approaches indicated the Art as a method both scientific and mystical, and one with many affinities with Cabala. The influences of Arabic thought on Lull’s outlook had of course long been known and studied by scholars, particularly the influence of the logic of A-Ghazāli.

Lull chiefly valued his Art for its missionary possibilities. He believed that an Art based on principles which the three great religions – Christianity, Judaism, Islam – recognized, provided infallible arguments for the conversion of all to Christianity. This passionate missionary aim was paramount in Lull’s life and work, the motive force behind his incessant promotion of his Art. This aim was afterwards partially forgotten but the Art continued to spread and proliferate as a method, an attempt at methodical thought using diagrams and letter notations.

The Lullian artist is not a magus: the genuine Arts are not magical. Lull carefully avoided the use of the images of the stars in his ‘elemental astrology’ and he constantly affirmed that his Art was based on ‘natural reasons’. But Lull, with his claims to the possession of a ‘universal art’, or key, may be said to prefigure the magus, and Lullism was to become inextricably bound up with the Hermetic-Cabalist philosophies of the Renaissance. Accepted by Pico della Mirandola, Lullism was the natural accompaniment of the Hermetic-Cabalist philosophy which underlies Renaissance Neoplatonism. In this atmosphere, Lullism took on the magical and occult flavour of that philosophy. The implicit connection of the Lullian emphasis on the elements with alchemy became explicit, and the pseudo-Lullian alchemy flourished. Many Renaissance magi, notably Cornelius Agrippa and Giordano Bruno, were Lullists, and by a development which has not yet been sufficiently analysed, the Art which its founder had tried to keep clear of magic became a vehicle for the Renaissance revival of magic and magic images.

Lullism does not lose its importance in the early post-Renaissance period. The immense significance of Lull’s Art for the formation of method is now realized. The seventeenth century in its constant search for method was always aware of the Art of Ramon Lull, even when it discarded it. Bacon and Descartes both knew it. The attentive reader of the Discours de la méthode can hear therein distant echoes of Lull. In fact it is not an exaggeration to say that the European search for method, the root of European ach...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Essays on the Art of Ramon Lull

- Essays on Giordano Bruno in England

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Lull & Bruno by Francis A. Yates in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.