eBook - ePub

Urban Geography

A Study of Site, Evolution, Patern and Classification in Villages, Towns and Cities

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Urban Geography

A Study of Site, Evolution, Patern and Classification in Villages, Towns and Cities

About this book

This book is divided into three parts. The first deals with typical settelements in each of the seven continents, the early stages of settlements, land surveys and general phases of town evolution. The second part discusses changes in site and patter, from Neolithic to modern times. The third part specializes in topographic and functional controls in modern towns. Chapters on Planning, Regional Surveys and Classification of towns close the book. There are about 300 specially drawn plans and diagrams of towns - which should appeal to the sociologist and town planner as well as to every serious student of geography.

This book was first published in 1949.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Urban Geography by Griffith Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

GENERAL FEATURES

“Urbanism has become so powerful an influence in human life that the very term which we use to express larger social loyalties is Citizenship.”

L. F. THOMAS.

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

Various types of human agglomeration

THE peculiar province of the geographer is to interpret the relation between man and his environment. For a generation there has been debate as to the closeness of this relationship, geographers being divided into two schools on the question. The Possibilist stresses the human aspect of the relation, the Determinist the environmental factor. The present writer belongs to the latter school, and has devoted much research to an evaluation of the relation in regard to the three main types of human agglomeration. These essential types are Race, Nation and City.

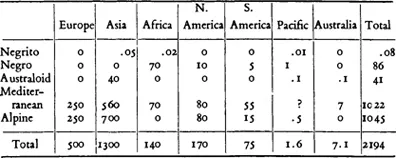

It is generally accepted that Man has differentiated into several varieties which we call Races. There is no complete unanimity as to the major races of man; but in his various researches the writer has adopted the following five classes:—Negrito, Negro, Australoid, Mediterranean and Alpine races. Readers who are interested are referred to the book Environment, Race and Migration (Toronto and Chicago, 3rd edn., (946) for the data behind this classification. Since there are about 2200 million people on the earth, it is clear that the human agglomeration which we call a race contains on the average about 400 million people. A somewhat closer approximation is given in the following table.

It may be well to explain that I have no belief in the classes instituted by Cuvier and Blumenbach about the year 1820. It is one of the inexplicable features of orthodox anthropology that it clings to these outmoded classes of Caucasian, Mongolian, Amerind, Polynesian, etc., etc. As I have explained at length in Environment, Race and Migration it seems to me obvious that we have similar migrations from the cradleland (in south central Asia) into each of the other continents (excluding Australia). Hence there are Alpine Broad-heads (brakephs) among the Asiatic, American and Polynesian aborigines. The same thing is true of the narrow-headed (dokeph) Mediterraneans; they also have spread from Asia into Europe, Africa, Polynesia, North and South America. For the purposes of this generalized table I have incorporated the Nordics with their kin the Mediterraneans. The Australoids include the wavy-haired aborigines of Australia as well as the much more numerous folk of the same race in southern India.

RACES OF THE WORLD (figures represent millions)

My book supports the thesis that man differentiated and migrated in response to environmental changes. The habitats of the five races (before the day of widespread emigration) were arranged in a series of zones centred about south central Asia. These zones considered in conjunction with the ‘fossil strata’ left by earlier migrations, enable us to decide upon the cradleland of man, somewhere in south central Asia, and upon the order of evolution of the races. The evolution is indeed indicated by the order of the five zones; the marginal Negritoes being the earliest, followed by the Negroes, Australoids, Mediterraneans and Alpines. The latter, occupying the centre of the racial zones, are (according to the laws of biological distribution) the latest evolved of the races of man.

In the second volume of the series somewhat similar considerations in regard to Nations were discussed. The Nation is a cultural unit and is not of the same type as the biological unit which we call a Race. A dozen complex factors go to produce a Nation. Many of these are found to be man-made, depending on social, political and military factors. However, the environmental factor persists throughout the development of a nation, and it is easy to show how vital is its influence in the development of a stable and lasting nation. One may mention the importance of the plateau pastures (Plaiuri) of the Carpathians in the survival of the Roumanian nation, in spite of repeated invasions by Asiatic peoples.

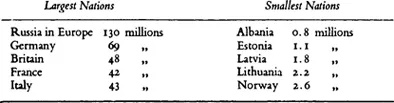

There are about 30 nations in the continent of Europe, and the book Environment and Nation (2nd Edition, Toronto, 1947) is concerned only with these. Since the total population of Europe is about 500 millions, it is clear that the average population of a European Nation is about 17 millions. This is a much smaller agglomeration than the Race; which averages about 400 millions. Of course some nations are much larger than this average figure, as the following table shows. Indeed only Roumania and Czechoslovakia are near this figure, the great number being much above or below 17 millions.

Just as the first volume, dealing with distribution of folk over the whole world led to somewhat new ideas in regard to Race, and interested anthropologists, so also it is hoped that the discussion of European Nations throws new light on some of the general principles of history. We shall see that a study of towns and cities will lead to certain novel conclusions which should be of value to Sociologists and Town-Planners.

How does the agglomeration of human beings which forms the unit in our present study, compare with those considered in the preceding volumes? The largest cities of the world, London and New York, consist of groups aggregating about eight millions. About 1911 there were 16 cities in the world whose populations exceeded one million, three being in the United States, two in Russia, and two in Japan. To-day there are over one thousand towns exceeding 10,000 people in the United States, and in some countries such clusters would be called ‘cities’. There is, however, no generally accepted figure which determines whether a cluster is a city, a town or a village. Perhaps we may call a settlement with less than 500 folk a village, while a town has a population between 500 and 10,000. There is also a great difference of opinion as to the optimum number of folk who should form one such aggregation, whether town or city. There is some evidence that a figure of about 40,000 is well suited to present urban conditions. Perhaps we may say, therefore, that a figure between 10,000 and 40,000 is the size of the cluster with which the term urban geography is usually associated. However, the giant city of to-day (which Mumford has christened ‘Megalopolis’) unwieldy and unesthetic as it is, has passed through the early stages of pioneer dwelling, village, town, city and metropolis, before it reached its present self-suffocating condition. Hence our study of the City necessitates a discussion of all the earlier forms of urban agglomeration, if we would understand its evolution. In other words this volume is concerned with all the stages of the third and smallest human agglomeration, though the ‘climax condition’ may be thought to be a city of about 40,000 people. In conclusion, therefore, we may say that racial clusters contain about 400 million people, national clusters about 17 million, and urban clusters about 20,000 people.

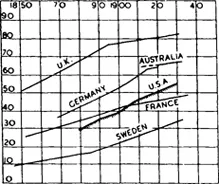

It is rather surprising that there is so little regular study of the characteristics of Urban Geography in the leading Departments of Geography to-day. When we realize that even in a new country like Australia no less than 64 per cent of the population is urban (Fig. 1), while in Britain it rises to about 80 per cent, it is clear that the geographical factors controlling city life are of the greatest importance to a large proportion of the people of the world. The historians and sociologists have given much more attention to the urban effects of the Industrial Revolution than have the geographers. It results, as in the case of Race and Nation, that the environmental factors in this interesting development have been to a large extent ignored, or at least submerged in the discussion of the sociological conditions.

FIG. 1. The rapidly increasing importance of Urban Geography is here illustrated by the rising percentage of urban populations. (Based on W. S. Thompson.)

There are several valuable studies by geographers in closely allied fields; for instance, Geddes’ Cities in Evolution, Van Cleef’s book on Trading Centres, or Rodwell Jones’ Geography of London River (London, 1931); but the sole example somewhat along the lines indicated above is in French, and is Lavedan’s Geographie des Villes (Paris, 1936). However, this small but stimulating book contains few maps or diagrams, and it makes little attempt to analyse the factors which have led to the many different types of towns and cities. In effect it does not lay stress on the environment of the site, nor on the stage of evolution of a given town in a more or less inevitable cycle of development, nor on the relation of the major centre of a district to the smaller clusters; all of which seem to the present writer to be significant features in the geography of the cluster under consideration.

The most valuable studies in allied fields are a number of books dealing with Town Planning. Of these the most helpful is that by Lanchester (London, 1925). Several of them give useful accounts of the evolution of the town in classical and medieval times. Of course the outstanding work in this field is The Culture of Cities by Lewis Mumford (New York, 1938). It is not too much to say that this book has opened a new outlook on the evolution of cities. Especially useful is Mumford’s concept of the Eotechnic and Paleotechnic types of city. I have used his classification to some extent in the sections dealing with the major features of town anatomy. There is no better study of the way in which social changes have brought about changes in the plans of cities; and he is the strongest protagonist of the Possibilist School because he is most interested in the human side of the problem. To many readers this is admittedly the most interesting side of urban geography; but the writer hopes to show that the complementary features, determined to a greater degree by the environment, must by no means be neglected if a full picture of the urban landscape—the supreme characteristic of our 20th century way of life— is to be appreciated.

Perhaps the main purposes of the present volume may best be understood by references to analogous work in other fields. Half a century ago there was a tremendous amount of data available regarding the various aspects of a normal topography. It was the great achievement of William Morris Davis to co-ordinate these data, and to produce his invaluable concept of a ‘Cycle of Normal Erosion’. It is unlikely that we shall ever be able to analyse and synthesize the data of city development so adequately that we can produce as logical a concept of a ‘Cycle of Town Evolution. We can but try. For one thing we are dealing with the irrational actions of Man, rather than with the inevitable actions of Nature. Hence the City Cycle cannot be as clear as the Landscape Cycle.

I have in my previous volumes shown how helpful is the ‘Zones and Strata concept’, when applied to the differentiation and migration of races, languages, etc. The growth of a city starts at a nucleus, spreads in definite functional zones (as indicated by the types of buildings), and embodies a mass of data regarding outmoded or demolished buildings, which can be considered as equivalent to the strata in the ‘Zones and Strata Concept’. I have worked out a number of lengthy examples of the use of this technique, primarily in the vicinity of Toronto and Chicago; but it is of course applicable to any other district. Turning to another aspect of the problem, Köppen has simplified the comparison of the innumerable climates of the world by his classifications and formulae. I have ventured to apply a new technique to urban evolution, which gives us formulae for any given town or city. These are quite manageable for towns with a population of 40,000 or less. Indeed it is easy to work backwards and to draw a plan fromthe formula, which is a close approximation to the real distribution.

THE SCOPE OF THE BOOK

Part I—General Considerations

In dealing with so varied a subject as villages and cities, it is very difficult to decide on the presentation of the vast body of material which is available in literature; or which has been collected by the writer ever since ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contents

- Illustations

- PART I. GENERAL FEATURES

- PART II. HISTORICAL

- PART III. TOPOGRAPHIC AND OTHER CONTROLS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX