- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gender and Sexuality in Russian Civilisation

About this book

Gender and Sexuality in Russian Civilisation considers gender and sexuality in modern Russia in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Chapters look individually at gender and sexuality through history, art, folklore, philosophy or literature,but are also arranged into sections according to the arguments they develop. A number of chapters also consider Russia in the Soviet and post-Soviet periods. Thematic sections include:

*Gender and Power

*Gender and National Identity

*Sexual Identity and Artistic Impression

*Literary Discourse of Male and Female Sexualities

*Sexuality and Literature in Contemporary Russian Society

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gender and Sexuality in Russian Civilisation by Peter I. Barta in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Critique littéraire russe. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

IV. Literary Discourses of Male and Female Sexualities

12 MARINA TSVETAEVA AND ISLAND-VARIANT EROS

Diana L. Burgin

In a February 1928 letter to her Czech friend, Anna Teskova, with whom she enjoyed one of her classic distant intimacies, Marina Tsvetaeva wrote: “I haven’t loved anyone — for a long time. […] I’m talking about love at liberty, under the sky, about unfettered love, secret love, not designated in passports, about the miracle of the strange there becoming here. You know, after all, that [for me] sex and age are beside the point” (Tsvetaeva 1991, 50).1

Beginning with her childhood secret love for the Devil, all her life Tsvetaeva had a bent towards unfettered, variant, and transgressive eros, a bent like “the sky’s — towards islands of bliss”, “blood’s towards the heart”, “lips’ to a spring…” (Tsvetaeva 1990, 355). These comparisons “from the book of likenesses”, as Tsvetaeva called them, come from the 1923 poem “A Bent” (“Naklon”), in which the poet speaker describes the kind of bent she has towards her addressee.

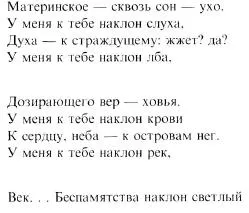

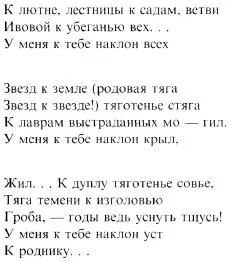

Like a mother’s — through sleep — hearing.I have towards you a bent of ear, inSpirit — with a sufferer: does it sting? yes?I have towards you the brow’s bent.When looking at the upper rea — ches.I have towards you the blood’s bent toThe heart, the sky’s — towards islands of bliss.I have towards you rivers’ bent.Lids’… Delirium’s bright bent toThe lute, a stairway’s to parks, a willowBranch’s to the fleeing of landmarks…I have towards you the bent of allStars to earth (a generic pull ofStars to a star!) — a flag’s gravitationTo laurels on graves of mar — tyrs.I have towards you a bent of wings.Veins… An owl’s gravitation to a hollow.The pate’s pull towards the coffin’sPillow, — for years I’ve been trying to sleep!I have towards you the bent of lips toA spring…

In this poem Tsvetaeva uses the word “naklon” in a neologistic, lexically transgressive way. In standard usage, “naklon” designates a physical, technical, or mathematical “incline”, “slope”, or “bent”, such as the incline of a head or an angle. Tsvetaeva, however, gives “naklon” a variant metaphoric meaning as if it were the etymologically related abstract noun, “sklonnost”‘ (inclination, predilection, bent). Her lexical variance has the effect of heightening the physicality and emotional intensity of the speaker’s erotic incline towards her addressee, making her bent towards him seem much stronger than the ordinary human inclination of one person for another. The poem “A Bent” illustrates that the typical Tsvetaevan subject’s feeling of strong attraction to another person often puts her fundamentally at variance with standard usage and convention. Therefore, her experience of desire is necessarily isolating, painful, and quite literally, ecstatic, out of her self, “a miracle of the strange there becoming here”, of the strange bent becoming her own inclination.

Despite its blatant transgressiveness, Tsvetaeva’s sexuality and its expression in her writing has remained a secret in scholarship until very recently. My own work on Tsvetaeva has focused on probably the most hidden (and controversial) aspect of her sexuality, her lesbianism, and, more importantly, the role her orientation to her own sex (and internalized fear of lesbians) played in her writing. Tsvetaeva’s most complex and self-revealing work on female same-sex love, as well as a unique Russian contribution to lesbian theory, is “Letter to the Amazon” (Lettre à 1‘Amazone), written in 1932 and revised in 1934, a prose epistle in French (which for Tsvetaeva was the language and culture of amorousness — liubovnost’). “Letter to the Amazon” is addressed to the American-French lesbian writer and famous Parisian salon-keeper, Natalie Clifford Barney. As I have demonstrated in a recent article on “Letter to the Amazon” (Burgin 1995), Tsvetaeva’s French text of (and against) female same-sex desire shows a “generic pull” of autobiographer to autopsy, and Tsvetaeva’s strange bent towards the twenty-year old corpse of her love affair (in 1914–16) with Sophia Parnok.

Tsvetaeva begins her polemic on lesbian love in characteristically paradoxical fashion. She quotes one of her addressee’s (Barney’s) maxims about lesbian lovers, and after adding her own interpretative twist to the maxim, she illustrates its truth by citing classic examples of heterosexual lovers: ‘“Les amants n’ont pas d’enfants’. True, but they die. All of them. Romeo and Juliet, Tristan and Isolde, the Amazon [Penthesilea] and Achilles, Siegfried and Brunhiide… And others… and others… in all songs, in all eras, in all places…” (Tsvetaeva 1983, 104). Tsvetaeva’s queer conflation of same-sex and opposite-sex lovers into a single category of childless lovers who die, allows the reader of “Letter to the Amazon” to infer that the traditional classification of romantic pairs on the basis of the sex and/or sexual orientation of the partners, is truly of no significance to her whatsoever.

Yet, Tsvetaeva does not transgress against all conventional distinctions bearing on sex, for a very traditional dichotomy underlies her own, in other ways idiosyncratic, typology of human sexuality: the dichotomy of nonreproductive versus reproductive sexuality. In “Letter to the Amazon” she illustrates her belief in the essentialness of this dichotomy through the story of her autobiographical protagonist, a typical “young girl” (jeune fille) from the North. This young girl’s primary longing is essentially, but not exclusively, platonic and homoerotic as she exhibits a natural aversion to men and yearns to couple spiritually and sexually with her “other me”, her kindred soul, a maternal “older woman” (1’aînée). One must note here that neither “young” nor “older” has primarily a chronological meaning in the way Tsvetaeva uses them in “Letter to the Amazon”; rather, “young” (in “young girl”) signifies “virginal, with homoerotic tendencies”, and “older” (in “older woman”) signifies “not virginal, essentially (by nature) lesbian”. The young girl’s yearning makes her vulnerable to “a trap of the soul” (un piege de l’ame), which is Tsvetaeva”s substantivizing metaphor in “Letter” for what she calls in “A Bent” the “generic pull of a star to stars”, or what we would call (female) same-sex attraction. The strangeness and strength of Tsvetaeva’s own bent in this direction requires an explanation to herself: “But how does it happen that the young girl, that creature of nature, goes astray so utterly, so confidently? Because of a trap of the soul” (Tsvetaeva 1983, 128). The typical young girl loses her way because of the ambivalence of her desire — while yearning for her own sex (and soul), she experiences an obsessive “inner need” (avoir inné) for a child, a need which compels her “inevitably” and tragically to leave her female lover for marriage and reproductive sex with her natural “enemy”, the man. Reproductive sex does give the young girl the child she wants so desperately, albeit a son, rather than the “little-girl-you” (une petite toi) she desired originally from her womanlover. Three years after her son is born, however, she runs into her ex-vvomanlover, who has a new young girl on her arm, and the former young girl realizes “what her son has cost her” (Tsvetaeva 1983, 136).

The impossibility of reproductive sex between female lovers angers Tsvetaeva and strikes her as a fatal flaw in nature. Unable to deal with her rage against nature, she projects it onto samesex (especially, lesbian) unions, onto all kinds of lovers‘ love, and onto childless marriages. For in much of “Letter to the Amazon” Tsvetaeva exercises her “inborn passion for contradiction”, justifying and even normalizing female same-sex love while arguing against her lesbian addressee’s “cause”, against her first lesbian lover (Parnok), and most tragically, against her renounced lesbian self (typical young girl).

It is important to emphasize that for Tsvetaeva, the flaw in female same-sex unions lies not in their homoeroticism. but in their incapacity to produce biological offspring — in spiritual offspring they are rich, richer than any marriage of mere bodies. Ironically, Tsvetaeva believes that the tragic flaw of female same-sex unions testifies to their perfection, “the perfect wholeness of two women who love each other” (Tsvetaeva 1983. 120). The paradox is that perfection, in the sense of achievement of one’s end, constitutes death, so by definition, lesbian perfection, like any other completion, is deadly.

At the same time, Tsvetaeva clearly implies in “Letter to the Amazon” that the deadly perfection of female samesex unions lends them a generative power of a different, spiritual, kind, making them the originating model for all non-reproductive, contra-nature passions — opposite-sex, same-sex, incestuous, even maternal. Just as medical men for centuries conceived of female genitalia in terms of male genitalia and explained female sexuality in terms of male sexuality, so Tsvetaeva conceives of all non-reproductive sexualities in terms of what was for her the primary secret “unfettered love” — love between women.

Because female same-sex unions and their childless opposite-sex, male same-sex, and incestuous same-and opposite-sex imitations are potentially deadly, they tend, according to Tsvetaeva, to be short-lived. One of the lovers, the one who must reproduce as nature demands, inevitably leaves the sterile love relationship, or in a frequently encountered ending of heterosexual lovers’ unions, convinces her lover to die with her and realize in death their souls’ eternal togetherness. According to the theory of human sexuality that Tsvetaeva articulates in “Letter to the Amazon”, only a few proud lesbian souls are able to sustain their rebellion against nature, eschew reproduction, and remain true till their deaths to their “fatal natural bent”. Nevertheless, in “Letter to the Amazon” Tsvetaeva tries to convince herself that being an older woman, or “fatal, natural” lesbian, condemns a woman in her biological old age, when all the impermanent (and ageing) “young girls” in her life have passed by (on their way to biological reproduction), to solitary confinement on an island.

Islands figure centrally in “Letter to the Amazon’s” imagery, geography, and ontology of female same-sex love. In deference to tradition, Tsvetaeva establishes a connection between female same-sex lovers and islands via the island of Lesbos, which she does not name in the text, but alludes to as “the island where the head of Orpheus washed ashore” and as the birthplace of “the great female unfortunate who was the great female poet” (Tsvetaeva 1983, 126/128). There are two types of islands in “Letter to the Amazon”: one of them is capitalized and the others are not. The capitalized Island appears to designate an unearthly, rigidly circumscribed, metaphoric locale where Tsvetaeva can situate her fear of lesbians and her own lesbian sexuality, safely away from herself: “The Island — an earth that is not earth, an earth which one cannot leave, an earth one must love since one is condemned to it. A place from where one can see everything, from where one can do nothing. Earth limited to a certain number of feet. Impasse” (Tsvetaeva 1983, 126).

In “Letter to the Amazon” Tsvetaeva embodies the typical inhabitant of the Island in the figure of the Other (L’Autre), the older woman and the lover of the young girl. At the end of the older woman’s life, she becomes physically celibate, and turns back into her own habitat: “She lives on an island. She creates an island. She is an island. An island with an infinite colony of souls” (Tsvetaeva 1983, 138).

Besides encoding islands as the secret home and identity, “not designated in passports”, of lesbians, Tsvetaeva reveals in “Letter to the Amazon” the way she can tell a lesbian apart from other women: not by the usual markings theorized and normalized by fin de siecle sexologists, such as short haircuts, broad shoulders, a masculine stride, mannish apparel and a fondness for smoking, but by “these women’s” possession of a certain air: “Young or old, these are the women who have the most soulful air. All other women with an air of the body do not have it, are not of it, or are it in passing” (Tsvetaeva 1983, 138/140). Tsvetaeva’s older woman is a lesbian, her young girl is made merely to pass for...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- STUDIES IN RUSSIAN AND EUROPEAN LITERATURE

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction to the Series

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- I. Gender and Power

- II. Gender and National Identity

- III. Sexual Identity and Artistic Expression

- IV. Literary Discourses of Male and Female Sexualities

- V. Sexuality and Literature in Contemporary Russian Society

- Index