- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Intimate Couple

About this book

As important as intimacy is in our personal and professional lives, intimacy as a theoretical and clinical factor still remains a phenomenon. Contributors to this work examine the many definitions of intimacy, putting forth a provocative discussion of the multi-faceted topic and offering the best possible clinical methods of creating intimacy and addressing its challenges.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

SECTION TWO

Methods of Creating Intimacy

CHAPTER 8

The Intimacy Dilemma: A Guide for Couples Therapists

Couples often encounter a dilemma when they relate intimately to one another. On the one hand, their intimate interactions are immensely rewarding. They reveal their private selves to one another, drop public roles, personas, and defenses, and share the parts of themselves that are ordinarily hidden and perhaps less socially desirable. Ideally, they receive one another’s disclosures with nonjudgmental acceptance and continued interest, attraction, and caring, and validate one another by indicating that they too have had such thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Assuming that some or all of these ingredients are present, the couple has an intimate interaction, and the effect of that intimacy can range from mildly pleasant to exhilarating. On the other hand, these kinds of intimate exchanges bring with them intense emotional vulnerability. The partners expose themselves to the risk of hurt and betrayal. They become more attached to each other and, as a result, are more likely to experience emotional anguish if separated. Intimate interaction, then, increases the potential for both joy and sorrow in the relationship. I call this dual potential the intimacy dilemma.

Most people reach adulthood with a subliminal if not explicit awareness of the risks of intimacy. As a result, most people find their own idiosyncratic ways of protecting themselves from those risks. These methods of protection are rarely fully conscious or acknowledged and can be relatively benign. Partners pursue separate interests, or retreat quietly to separate parts of the house. Self-protection may also involve subtle distancing behaviors, such as avoiding eye contact with the partner or withdrawing affection. Petty quarrels have a similar impact. Some self-protective behaviors are considerably more destructive to the relationship, however: having affairs, developing a critical, verbally denigrating stance toward the partner, working long hours away from home, and so forth.

Couples also frequently get into conflict about intimacy itself. They can find themselves locked into power struggles over how much time to spend together, how much to disclose to or to listen to one another, how often and under what circumstances to have sexual relations, and how much touching and affection to give and receive. Research evidence indicates that these kinds of intimacy tugs of war are associated with the most therapeutically recalcitrant couples, and that these kinds of interactions are characterized by rapidly escalating anger during conflict (e.g., Babcock & Jacobson, 1993).

It is important for therapists to understand intimacy and help couples negotiate the intimacy dilemma. Research indicates that intimate contact brings many benefits with it, not only for relationships but also for individual health and well-being (see review by Prager, 1995). Intimacy serves as a buffer against the pathogenic effects of stress while self-concealment is associated with poor health, particularly when the social network lacks intimate relationships. The ability to confide is an especially important component of couple relationships; without it, they provide no buffer against the effects of stress. Further, poorly functioning relationships are themselves associated with negative outcomes, particularly depression (e.g., Beach, Sandeen & O’Leary, 1990). Finally, intimate relationships are routinely rated as more satisfying and rewarding than nonintimate relationships (e.g., Antill & Cotton, 1987).

Therapists can assist couples in their efforts to navigate the waters of the intimacy dilemma although they cannot remove the risks that intimacy brings with it. Therapists can help couples find a rhythm which allows them to experience the joy and satisfaction of the intimate contact they desire, while at the same time allows them to withdraw from intimacy without undue guilt or a disruption of the bond between them.

Problems with intimacy can be some of the thorniest that the couple therapist faces. First, they present an assessment challenge. They may be at the forefront of a couple’s presenting complaints, but are just as likely to be subliminal, hidden within a pattern of destructive conflict, distancing, or emotional abuse. Second, they are a treatment challenge. In order to reap the benefits of intimate relating, couples must often rebuild a trust that has been seriously eroded from years of destructive interaction. Partners may be justifiably resistant to interventions that increase their vulnerability when they have learned over the years that they cannot trust their partners to be sensitive and gentle. They may claim that they want nothing more than to stop the fighting and the pain that goes with it. Most couples want this and more, however. They want the many benefits that intimate contact provides.

In order to maximize their effectiveness as guides through the intimacy dilemma, couple therapists must have access to two things—a conceptual model for understanding intimacy issues in couple relationships, and a set of strategies and techniques for helping couples to effectively negotiate the intimacy dilemma. My purpose is to provide a conceptual model, and to review couple therapy techniques that will benefit couples who wrestle with this dilemma. Specifically the chapter proposes the following,

1 Couple therapists need a clear definition of intimacy. First, this chapter presents a conceptual model that defines intimacy and the individual and relational contexts within which intimate interactions take place.

2 There are normal intimacy dilemmas that all couples face. Next, I outline normal intimacy dilemmas involving individual differences in (a) people’s needs for intimacy, (b) the processes by which people meet their intimacy needs, (c) the various psychological needs people hope their intimate interactions will fulfill, and (d) fears of the risks of intimacy.

3 Couples with relational difficulties are often coping with incompatible preferences for intimate relating. Third, I discuss three sources of intimacy incompatibility: (a) incompatibilities stemming from normal individual differences brought into the relationship, (b) incompatibilities stemming from one or both partners’ individual problems with being intimate (perhaps stemming from their own developmental history), and (c) incompatibilities stemming from either or both partners’ inability to constructively communicate about intimacy and solve problems related to it.

4 Couples’ intimacy dilemmas can be assessed through self-report and observational techniques. Fourth, I will demonstrate how techniques familiar to cognitive-behavioral therapists can be used to assess a couple’s intimacy-related compatibilities and conflict.

5 The treatment of intimacy-related dilemmas usually requires both acceptance and change-oriented treatment strategies. Lastly, couples often need assistance in setting obtainable goals and focusing on appropriate targets. I suggest ways of matching intervention approaches to specific therapeutic goals and targets.

A MULTITIERED DEFINITION OF INTIMACY

Neither scholars nor clinicians have been able to agree upon what intimacy is. The psychological literature offers up a cornucopia of intimacy concepts and definitions, varying in scope from those referring only to microbehaviors within interactions (e.g., maintaining gaze, leaning forward while communicating) to those encompassing every aspect of a relationship (e.g., sexuality, emotional expression, shared recreation, etc.) (see Prager, 1995, for a detailed discussion). Lay populations hold overlapping but not identical conceptions that emphasize self-disclosure, intense emotional experiences, and self-transcendance (e.g., Register & Henley, 1992). I have defined intimacy as a kind of interaction that has experiential components and sequelae (Prager, 1995). Further, I define intimacy within its individual and relational context. Individual capacities and fears on the one hand, and relational communication processes on the other, affect how the intimacy process unfolds and how it affects the individual partners and their relationship.

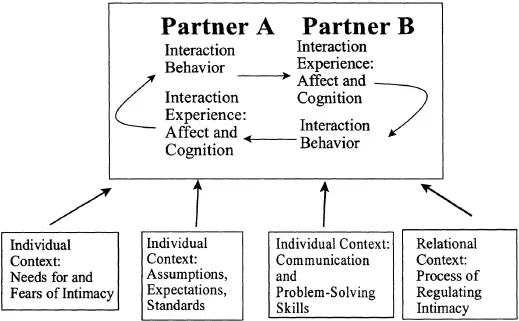

Figure 1 illustrates a multitiered conception of intimacy. Within the upper tier are aspects of the intimacy process itself. The lower tier contains contextual factors that affect the intimacy process.

Intimate interactions Intimate interaction has a behavioral, a cognitive, and an affective component. Its behavioral component is the act of sharing, verbally or nonverbally, something that is private and personal with another. The private and personal nature of what is shared affirms the specialness of the relationship and the other person. When one partner shares authentic and private aspects of him or herself, the other partner thereby has the opportunity to really know the partner who shares and to convey acceptance to him or her. The risk of sharing is that acceptance is not always the outcome of the sharing. Sharing therefore involves a willingness to trust on the part of the one who shares and, ultimately, a history of trustworthiness on the part of the other.

Figure 1 Intimate Interaction in Its Relationship Context.

The cognitive and affective components together make up the experiential component of intimacy. The cognitive component is the perception, within the interaction, that one is truly and fully understood by the partner. Equally satisfying is the perception that one truly and fully understands the other, that the other has let him or herself be fully known. There is evidence, that, particularly for women, one or both are necessary in order for the interaction to fulfill important psychological needs (Prager & Buhrmester, in press).

The affective component of intimacy consists of the positive feelings partners have about themselves and their partners during (or as a result of) the interaction. Warmth, closeness, empathy, laughter, pride in the other and so forth are an integral part of intimacy. Otherwise, the interaction may be open and blunt and may lead to mutual understanding, but it is not intimate (Derlega & Chaikin, 1975).

The context of intimacy Intimate interactions do not exist in a vacuum, but affect and are affected by characteristics of the individual partners and of their relationship. There are individual and relational factors that affect the quality of intimate interactions and each partner’s capacity for reaping their benefits. In order for intimate interactions to satisfy the needs of both partners, these contextual components must be intimacy-enhancing or, at least, intimacy-allowing.

The individual context refers to each partner’s individual capacity for intimacy. Individual factors fall into three categories: behavioral, cognitive, and affective.

1 The term individual behavioral capacities refers to the communication skills that each partner is able to make use of in the context of the relationship. Of primary concern are (a) active listening and empathic expression, (b) the ability to articulate inner experience (e.g., see Davis & Franzoi, 1987), and (c) the ability to convey that one has heard, understood, and can accept the other’s message.

2 Relevant individual cognitions are each partner’s assumptions, expectations, and standards about intimate contact, and how those cognitions get expressed or acted upon within the relationship.

3 Individual affective characteristics include each partner’s individual need for intimacy and related provisions and each partner’s fears of intimacy.

The relational context refers to other characteristics of the partners’ relationship that affect their opportunities for intimate contact. Theoretically, these could include any aspect of the relationship. In this chapter, I will focus on the intimacy regulation process (i.e., the set of behaviors and communication processes partners typically use to regulate intimate contact).

In sum, this definition includes behavioral, affective, and cognitive aspects of intimacy, and it defines individual and relational contextual variables that affect intimate interaction. Interventions can target the intimacy process itself or they can target individual or relational contextual factors that affect those interactions.

Normal Intimacy Dilemmas in Couple Relationships

When two individuals decide to become a couple, they bring with them a host of individual differences in needs, preferences, and coping styles (McAdams, 1988). Variations in people’s needs and preferences for intimate contact can be a source of intense frustration and distress. If partners fail to identify ways to meet their respective intimacy needs, they are likely to find themselves dissatisfied with their relationship. Since partners are more likely than not to have different needs and preferences, even the most satisfied and harmonious partners will eventually confront those differences and attempt to resolve them.

The need for intimacy encompasses two interwoven needs: a need for another person to fully know and understand us as we know and understand ourselves, and a need for that same person to also fully accept us as we are (also see Jourard, 1971, and Reis & Shaver, 1988). Intimacy needs can differ from one person to the next in several ways.

People have intimacy needs of varying strengths Individuals vary in the strength of their needs, and these individual differences affect how they perceive and behave in different situations (e.g., McClelland, 1985). Henry Murray’s typology of needs (1938) and his concept of a need as a stable individual disposition gave birth to a research tradition that reliably measures need strengths and has demonstrated their effectiveness for predicting behavior. McAdams (1984) measured intimacy motivation by coding stories people wrote in response to TAT stimuli for intimacy-related content. Intimacy-related content was defined as any theme related to relationships that involved positive affect and people engaged in two-way dialogues. The strength or pervasiveness of intimacy-related content was further scored through themes of psychological growth and coping, commitment or concern, time-space transcendence, union, harmony, surrender of control, escape to intimacy, and connection with the outside world. People whose stories contained these themes were more likely to self-disclose in group interaction, reported having more meaningful conversations during the week following the assessment, and described their relationships as more satisfying (Craig, Koestner, & Zuroff, 1994; McAdams, Healy & Krause, 1984).

People vary in how they meet their needs for intimacy Not unrelated to individual need strengths are the ways that people get their needs for intimacy met. As psychologists, we often think of intimacy in terms of intense interaction (e.g., Beach & Tesser, 1988). My own research has shown that peopl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword to The Intimate Couple

- Preface

- Section One: Overview

- Section Two: Methods of Creating Intimacy

- Section Three: Intimate Challenges

- Appendix A

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Intimate Couple by Jon Carlson, Len Sperry, Jon Carlson,Len Sperry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.