![]()

Chapter One

INTRODUCTION

There are two distinct approaches to the study of motivation. One stratagem is a product of academic, experimental procedures, while the second is an outgrowth of clinical, non-experimental methods. Each of the approaches has unique advantages and disadvantages. But all investigators in this field are guided by a single basic question, namely, Why do organisms think and behave as they do?

The Experimental Stratagem

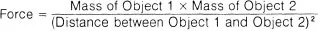

To answer the above question, the dominant experimental stratagem has been to identify the immediate determinants of behavior and then specify the mathematical relations between the variables. In this manner a “model” of behavior is developed. This ahistorical approach is guided by the laws of motion developed in the physical sciences. For example, assume that you want to predict the force of attraction of one object toward another. To predict this accurately, you need to know the masses of the objects. These might be considered their “personalities” or stable dispositions. In addition, to predict the force of attraction, you must know some other facts, such as the distance between the two objects. It could then be ascertained through empirical tests that the force of attraction between the objects is, in part, directly related to their masses and inversely related to the square of their separation distance:

Now consider a problem concerned with human attraction. Children are playing in the family room and their parents call them to the kitchen for dinner. A psychologist might want to predict how long it takes the children to leave their ongoing play activities (the latency of the response) or how swiftly they come to the dinner table once the approach response has been initiated (the intensity of the response). To do this, the psychologist must identify the determinants of the approach to food and discover their mathematical relations.

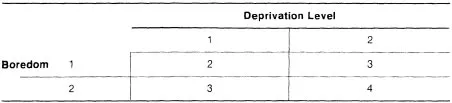

Table 1–1 ADDITIVE RELATION OF DEPRIVATION AND BOREDOM

Introspection on the part of the reader will readily reveal some of the factors that influence the latency and the intensity of the food-related approach response. For example, it is likely that the longer the time since the children last ate (deprivation level) and the more gluttonous they are (motive for food), the faster will be the speed of approach and the shorter the latency of going to the kitchen. In addition, serving hot dogs rather than spinach (incentive value), being engaged in a boring play activity, fear of parental punishment, and the absence of fatigue are also likely to increase the measured index of motivation.

Ideally, the psychologist would like to develop a model for hunger motivation. This model might take the following form:

Hunger motivation = (Deprivation level × Motive for food × Incentive value × Fear) + Boredom with current activity – Fatigue

In sum, the answer to the question of why people behave as they do is given by a mathematical equation that includes all the determinants of an action. Note that the particular history of the children is not needed to predict their response latency or intensity. That is, why they have come to love hot dogs or what has caused their boredom or fatigue is not relevant. What is essential is that the present values of these constructs be known.

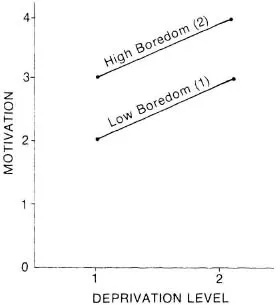

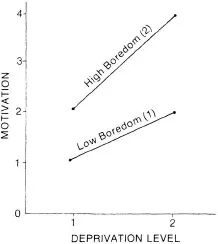

Figure 1–1. Additive relation of deprivation and boredom.

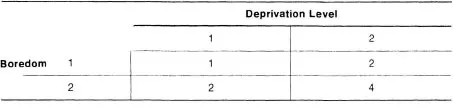

Table 1–2 MULTIPLICATIVE RELATION OF DEPRIVATION AND BOREDOM

Of course, listing all the determinants of a particular action is exceedingly difficult, and specifying their mathematical relations is even more difficult. The problems are especially complex because the units of measurement of the various determinants of behavior are not equivalent. For example, is eight hours of food deprivation equivalent to the incentive value of a steak? This may sound like a facetious question, but it highlights the complications of developing standard units of comparison for factors that are much more disparate than apples and pears.

It is possible, however, to discover whether the components in a motivational model are related additively or multiplicatively. Assume, for example, it is hypothesized that deprivation and boredom are related in an additive manner, as indicated in the previous equation. In Table 1–1 deprivation and boredom are assigned the arbitrary values of one and two. The body of the table shows the total of these values. These totals are plotted in Figure 1–1. Note that the lines in Figure 1–1 are parallel.

On the other hand, if deprivation and boredom are hypothesized to relate multiplicatively, the values are changed, as shown in Table 1–2. When plotted in Figure 1–2, it can be seen that the lines diverge. Thus, parallel lines reveal additive relations, while diverging lines indicate a multiplicative relationship between the variables.

Figure 1–2. Multiplicative relation of deprivation and boredom.

To ascertain the relations between components in models, psychologists typically manipulate the strengths of the variables in an experimental setting, and graphs similar to those in Figures 1–1 and 1–2 are generated. Thus, for example, bored and not bored subjects may be deprived of food for four or eight hours and then called to a “food break.” The speed or latency of their response is then assessed, and the mathematical relation between boredom and hunger is ascertained.

In sum, the experimental approach to motivation attempts to develop mathematical formulas or models that account for behavior. The models are tested in experimental settings where there is control over the variables under consideration. The observed behaviors provide evidence for the validity of the model. This ahistorical approach typically is used to explain a limited range of phenomena with accuracy.

The Clinical Stratagem

To answer the question of why people behave as they do, psychologists studying motivation from a clinical orientation assert or presume that there are one or more basic principles of behavior, such as “people strive to fulfill their potential” or “people strive to satisfy their aggressive and sexual urges.” Then a broad range of clinical, historical, anecdotal, literary, and experimental evidence is marshaled to support this contention. In contrast to the experimental approach, there is little attempt to develop a formal or mathematical model. But there is an endeavor to encompass a wide breadth of phenomena. For example, in the Freudian system, the striving to satisfy sexual and aggressive urges is presumed to be manifested in slips of the tongue, dreams, neurotic behavior, and artistic creativity. Often an historical analysis of how the person has become what he or she is provides a basis for inferences about underlying motivational tendencies. These notions are not really subject to definitive proof or disproof, but they are useful in generating ideas and research and in providing insights about the causes of behavior.

Individuals associated with the clinical stratagem often are psychiatrists or clinical psychologists interested in the adaptation of individuals to their environment. Thus, they also frequently are social commentators about “quality of life” and can become visible public figures who add to our vocabularies and indirectly alter numerous aspects of our lives. For example, concepts such as “id,” “defense,” and “ego,” from psychoanalytic theory, or “self-disclosure,” “sensitivity training,” and “self-actualization” from humanistic psychology change how we perceive ourselves, how we perceive others, and perhaps influence important portions of our lives.

Plan of the Book

In this book, seven approaches to the problem of motivation are presented, along with related conceptions or ideas. The grouping of the theories is arbitrary. The initial two conceptions presented are Freudian psychoanalytic theory and Hullian drive theory. Although these theories differ greatly because of their respective allegiances to the clinical and experimental stratagems, they are paired because both assume that tension or need reduction is the basic principle of action. In addition, these two theories have dominated the study of motivation and thus are given more space than most of the remaining conceptions.

The second group of three theories includes Lewin’s field theory, Atkinson’s theory of achievement motivation, and Rotter’s theory of social learning. These three are joined because all are expectancy-value theories. That is, behavior is assumed to be a function of the expectancy of goal attainment and the incentive value of the goal. All also adhere to the experimental, model-building stratagem.

Attribution theory and humanistic psychology are the last conceptions to be presented. These approaches differ in a number of fundamental ways, but both assume that humans strive to understand themselves and their environment and that growth processes are inherent to human motivation. Thus, these theories most contrast with the Freudian and Hullian approaches.

Within this list of seven theoretical approaches, the first and last (Freudian and humanistic psychology) most closely follow the clinical stratagem. But the theories can be compared and contrasted in a number of other important respects. For example, Hull and, at times, Freud accepted a mechanical or a materialistic view of humans. Behavior often is interpreted without invoking mental processes or thoughts as explanatory concepts. Rather, humans are considered machines with input (antecedent) and output (consequent) connections that need a source of energy to be “driven.” On the other hand, expectancy-value theorists such as Lewin, Atkinson, and Rotter, attribution theorists such as Heider and H. H. Kelley, and humanists such as Maslow, Rogers, and Allport accept a cognitive view of humans. It is contended by these theorists that mental events intervene between input-output relations and that thought influences action. Furthermore, many of these theorists assume that individuals are always active and are not in need of any “motor” to get behavior started. The relation between the mind and the body, or what is known as the Mind-Body Problem, and the necessity of energy concepts to explain human motivation are examined in greater detail in the subsequent chapters.

The research focus of each theory also differs. For example, Freudian theory led to an examination of defense mechanisms, aggression, dreams, and sexual behavior; Hullian drive theory is empirically supported by observations of hungry animals running down a maze for food, or humans receiving an aversive puff of air in the eye; and Atkinson’s theory of achievement motivation has most thoroughly examined the choice between achievement-related activities that differ in difficulty level. Thus, each theoretical approach appeals to a particular reference experiment or observation to demonstrate its validity. The theories are not commensurate; that is, there is not a domain or a behavior at which they all can be compared so that one theory can be judged as “better” or more accurate than the others. Rather, the theories focus upon disparate phenomena and stand side by side with their unique ability to account for certain observations. There is not a hierarchical ordering of “Truth,” although there are occasions when two or three of the theories can be compared with respect to a certain observation.

The theories presented in this book were, for the most part, formulated by clinical psychologists and psychiatrists. Individuals such as Freud, Rotter, Maslow, Rogers, Allport, and G. Kelly form the heart of many textbooks in the field of personality. These theories, in varying degrees, focus upon the person and intra-psychic influences on action. This does not imply that the environment or the social context of behavior is neglected, for such a neglect would make predictions of human action impossible. Rather, situational and social factors are recognized, but they frequently are not the center of attention.

It is increasingly evident, however, that we are social animals and that the study of motivation must be broadened to include social concerns. Thus, this book examines topics related to social behavior, such as altruism, cognitive balance, competition and cooperation, group formation, and social facilitation, to name just a few topics of concern.

Summary

There are two basic approaches to the study of motivation: experimental and clinical. The former attempts to develop mathematical models that account for limited aspects of behavior, while the latter posits...