- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

British Sign Language

About this book

This first linguistic study of British Sign Language is written for students of linguistics, for deaf and hearing sign language researchers, for teachers and social workers for the deaf. The author cross-refers to American Sign Language, which has usually been more extensively studied by linguists, and compares the two languages.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

What is BSL?

This chapter is intended as an introduction to British Sign Language (BSL) for those who have little previous experience of it. I shall attempt to answer the general question posed by the title of this chapter by trying to answer a series of questions of the kind typically asked by hearing people coming across sign language for the first time.

Let us start, however, with a rough definition of the term ‘BSL’ as it is used in this book. ‘BSL’ refers to a visual-gestural language used by many deaf people in Britain as their native language. The term ‘visual-gestural’ refers to both the perception and production of BSL: it is produced in a medium perceived visually, using gestures of the hands and the rest of the body including the face. Although the term ‘manual’ is sometimes used to describe BSL, I have avoided it here because of the implication that only the hands are involved. As we shall see, it is true that most research has concentrated on what the hands do, but recently we have become more aware of the important role played by body stance, head movement and facial expression.

BSL is used by many deaf people: we do not know exactly how many, though an estimate of 40,000 has been made, based on a survey in the early 1970s, of the number of deaf people attending clubs or known to social workers (Sutcliffe, personal communication). These people are mostly born deaf, to either deaf or hearing parents (but also hearing people born to deaf parents), and learn BSL either from their parents (if deaf), deaf siblings, or deaf peers. I have described BSL as these people's ‘native language’ because it is the language they know best and are most comfortable with. It may not necessarily be the first language they are exposed to, however. The particular way in which BSL is acquired will be discussed in chapter 7.

I shall now try to give some more idea of what BSL is like by attempting to answer the following questions: (1) Is sign language universal? (2) Is BSL based on English? (3) Is BSL iconic (or pictorial)? (4) Is BSL a language?

Is sign language universal?

People who ask this question are generally interested in knowing whether sign language, as used by the deaf, is universal in the sense of being the same all over the world. When told that it is not they are usually surprised and say that it should be. The idea that sign language must be universal seems to be very widespread, so it is interesting to consider why this should be so. I would suggest that the idea is based on one or more of the following erroneous assumptions: (i) sign language developed in a way radically different from spoken language; (ii) sign language is natural, instinctive and pictorial, so need not be learned; (iii) because deaf people from different countries appear to be able to communicate with one another, then they must be using the same language. Let us consider these assumptions.

It is well known that despite similarities in grammar or vocabulary between certain spoken languages, there are a large number of spoken languages of different types. Estimates of the exact number vary, largely because of the difficulty of determining how dialects or varieties of language should be grouped together, but one estimate is ‘more than three thousand’ (see Fromkin and Rodman, 1978, p. 350). Many spoken languages are mutually unintelligible, which means that the speaker of one language will not be able to understand the speaker of another language when each is using his or her own language. Languages develop in communities, through contact between speakers, so communities that are geographically separated from one another are likely to have different languages. This will apply to sign languages as well as to spoken languages.

We have little information about the origin and history of sign languages, but they seem to have developed where there were communities of deaf people, usually linked to deaf schools or welfare institutions. Before such institutions were formed (in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Britain: see next chapter), deaf people would have been rather isolated from one another, although it is very likely that some kind of signing would have been used in various families. As a deaf community became established in a country, through links between various institutions, we may assume that a national sign language gradually developed, although differences related to different schools, for example, would have survived (see chapter 6 on variation in BSL). Deaf people would have had very little contact with one another across national boundaries, however, so there would have been no reason for an ‘international’ sign language to develop.

It may be argued that there was nevertheless some contact between educators of the deaf in different countries, the best documented link being that between France and the USA in the early nineteenth century (see next chapter). It is thought that because French manual methods were introduced into the first American school for the deaf, that American Sign Language (ASL) is descended from French Sign Language (FSL). There are certainly similarities between the two sign languages, but it seems likely that some kind of American Sign Language was already in existence, and that it was influenced by, rather than descended from, French Sign Language (cf Woodward, 1978). The effect of contact between deaf communities, or lack of it, is illustrated by the fact that ASL appears to be more similar to FSL than to BSL.

Linguistic research on spoken language has focused on similarities as well as differences in languages, searching for what may be universal or common to all languages. It may be that sign languages will turn out to have certain features which they share with one another and with spoken languages, but further research is needed to establish this. For the moment we can note that sign languages appear to differ from country to country in a similar way to spoken languages, and to have grown up in separate communities.

The second assumption, that sign language is ‘natural and instinctive’ may come from hearing people's association of the term ‘sign language’ with ‘body language’ or non-verbal communication. Non-verbal communication is not usually recognized as part of spoken language, and yet at least part of it seems to be learned and culture-specific (cf Hinde (ed.), 1972, Morris et al., 1979). Japanese people beckon with the palm down rather than up, for example, so that the gesture looks a little similar to the Western person's farewell gesture. Another common interpretation of the term ‘sign language’ is as an ad hoc gesture system used to communicate with people whose language one does not speak. This kind of system is usually closely tied to the immediate context (e.g. relying heavily on pointing to concrete objects) and used for conveying only limited messages, and is invented when it is required. This is not true of deaf sign language, however, which is not limited to the immediate context and can be used to communicate about a wide variety of topics. Nevertheless, its visual medium may lead people to expect it to be iconic and pictorial, or ‘natural’ in the sense of there being a ‘natural’ relationship between signs and what they represent. Meanwhile, however, we may note that the difficulty often experienced by hearing people in learning sign language means that it cannot be entirely ‘natural’ and ‘instinctive’.

The final assumption, that deaf people from different countries must be using the same language because they can communicate with one another, was empirically tested by Jordan and Battison (1976), using subjects attending a World Federation of the Deaf Congress in Washington, D.C. Signers from different countries were asked to watch video tapes in various sign languages (American, Danish, French, Hong Kong, Italian and Portuguese), describing one of an array of pictures in front of them. Their accuracy in selecting the correct picture was measured. The results showed that for each single picture that the subject had to pick out, the percentage of errors was higher when the description was in a sign language other than the subjects’ own. The conclusion, that ‘deaf signers can understand their own sign language better than they can understand sign languages foreign to them’ (p. 78), seems simple and uncontroversial, but at least it is evidence against the myth that sign languages are the same everywhere.

So how is it that we can observe signers communicating across national boundaries? It seems likely that deaf people are using a kind of compromise sign system, assessing the differences between their own sign languages and modifying them accordingly, borrowing signs from one another's languages and using mime where necessary. Deaf people are in fact quite expert at using mime on an ad hoc basis, through continual experience of trying to communicate with hearing people. Also, because their native sign languages generally have lower social status and fewer prescriptive norms attached to them than many spoken languages, I would suggest that deaf signers might be less inhibited about modifying their sign languages for ease of communication than would, say, speakers of English or French.

So sign language is not universal, and we are gradually finding out more and more about the sign languages of different countries. ASL has been investigated in the most detail (see e.g. Siple (ed.), 1978, Klima and Bellugi, 1979, Wilbur, 1979), but other sign languages currently being investigated apart from BSL include Japanese Sign Language (see Tanokami et al., 1976), Chinese Sign Language (see Klima and Bellugi, 1979), Swedish Sign Language (SSL) and Danish Sign Language (see e.g. Ahlgren and Bergman (eds), 1980). There has also been some research done on sign languages in less developed countries where deaf people tend to be less institutionalized and more integrated with hearing people (see e.g. Washabaugh, 1980, 1981).

As a final illustration of the fact that sign languages differ, at least on the level of vocabulary, here are some examples of different signs used to translate the English words ‘woman’ and ‘England’:

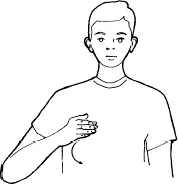

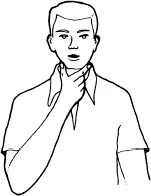

BSL WOMAN: index finger stroking right cheek

SSL WOMAN: cupped hand outlining breast

ASL WOMAN: thumb stroking cheek, then flat palm at eye level, neutral space

BSL ENGLAND: rubbing of fingerspelled ‘e’

SSL ENGLAND: thumb and index finger clasping chin

ASL ENGLAND: hands clasped, palms down, moving back and forth

These examples illustrate the same English word being translated into different forms in different sign languages. In addition, the same form may have different meanings in different languages. For example, the sign meaning ‘true’ in BSL means ‘stop’ in ASL and ‘right’ or ‘correct’ in SSL. Also, the signs for ‘good’ and ‘bad’ in BSL mean ‘male’ and ‘female’ respectively in Japanese sign language.

Is BSL based on English?

People who do not expect sign language to be universal often seem to expect BSL to be based on English. They may assume, like some of those who think sign language is universal, that sign languages do not develop spontaneously like speech, but in addition, they tend to assume that BSL must have been invented by hearing people to help deaf people communicate or learn English. BSL should not be confused with the Paget Gorman Sign System (PGSS) which was indeed invented as a contrived system to help deaf people learn English. PGSS is a manual representation of English designed to be used simultaneously with speech, and is used in a few British schools for the deaf. There is also some discussion currently about the possible role of BSL in schools for the deaf, but BSL is not widely accepted in the classroom (see chapters 2 and 7). In some schools signs from BSL are used simultaneously with spoken English, but in this case the syntax of the signs is modified to fit the structure of English (as in ‘Signed English’: see chapter 2, p. 37).

However, BSL as used natively by deaf people is quite different from English. Individual signs in BSL are roughly equivalent to words in English and are translatable as such, but they do not directly represent either the sounds or meanings of English words. The only part of BSL which directly represents English words is the fingerspelling system, or manual alphabet. This alphabet is two-handed (unlike the one-handed system used in conjunction with ASL and some other sign languages) and is a series of hand configurations representing the letters of the alphabet (see illustration on next page). It is used by signers for spelling English names and places, or words for which there is no equivalent sign.

BSL signs which are not part of the fingerspelling system are made up of a different set of hand configurations from those of the manual alphabet, and involve a variety of movements and locations on the body. The activity of the hands is accompanied by various kinds of non-manual activity, such as facial expression and head movement. Just as the words of spoken language can be described as being made up of individual sounds or ‘phonemes’, signs can be described as being made up of various components, such as places on the body where the sign is made, hand shape and arrangement, and movement. The description of individual signs will be discussed in detail in chapter 3.

As I suggested above, there is no one to one correspondence between the meanings of BSL signs and English words. Some signs may have more than one possible English translation, and some English words may hav...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Language, Education and Society

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- General Editor's preface

- Preface

- 1 What is BSL?

- 2 The origin and use of BSL

- 3 The structure of BSL signs

- 4 The grammar of BSL

- 5 BSL and ASL

- 6 Variation in BSL

- 7 The acquisition of sign language

- 8 Doing sign language research

- 9 Conclusion: BSL and linguistic theory

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access British Sign Language by Margaret Deuchar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.