![]()

J. G. Ballard (1956–1975)

I was joking about taking walls too seriously, but in fact the sort of architectural spaces we inhabit are enormously important—they are very powerful. If every member of the human race were to vanish, our successors from another planet could reconstitute the psychology of people on this planet from its architecture. The architecture of modern apartments, let's say, is radically different from that of a baroque palace.

(Ballard, ‘Interview with Graeme Revell’, 1984c, p. 44)

POST-CATASTROPHIC, EXISTENTIALIST DWELLINGS

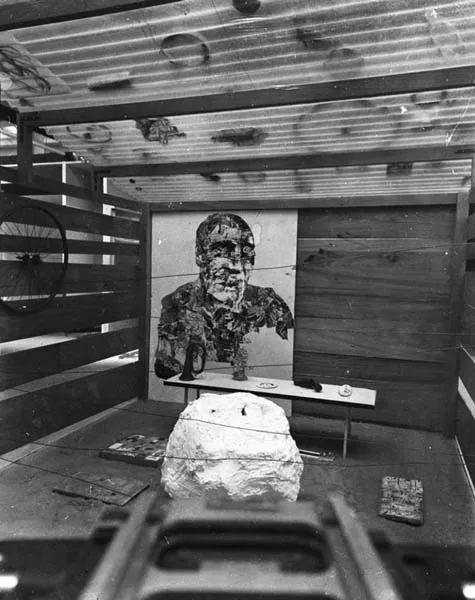

In 1956, the year Ballard published his first short story ‘Prima Belladonna’, the Pop Art exhibition This Is Tomorrow was staged at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, by a loose aggregation of artists, designers and writers known as the Independent Group and assembled at the Institute of Contemporary Art. The exhibition consisted of a dozen stands, each one the collaboration of a different team. The construction put up by sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi was realized with the external collaboration of architects Alison and Peter Smithson, photographer Nigel Henderson and his anthropologist wife Judith Stephen. The installation, titled Patio and Pavilion (Figure 1.1), comprised a sort of small and temporary storage room made of recovered wooden boards with a corrugated plastic roof. On top, inside and outside, there were stones, bricks and found objects gathered on the roads around Bethnal Green in London's East End. As architect Andrea Branzi suggests:

Hence the English artists, architects and intellectuals in the post-war period looked courageously at the small objects washed up on the roadways of generic outskirts by the tidal shift of a world that was ending while another was being born, and they all found themselves to be denizens of those outskirts.

Eduardo Paolozzi's pavilion was an almost heartfelt acceptance of this transition and showed an extraordinary cheerfulness for this new empty space. The ‘great hopes' of modernity, the megaprojects, the new cathedrals no longer exist; in their place lies an opaque territory of objects, of temporary storehouses, but also the courage of a great vitality. (2004, p. 439)

Figure 1.1 Nigel Henderson, Eduardo Paolozzi, Peter and Alison Smithson (known as Group 6), Patio and Pavilion environment designed for This Is Tomorrow exhibition held at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1956. © Tate, London 2012.

The installation was a tangible meditation on the demands of the habitat and a warning against the technocratic fetishism of urban planning. As Claude Lichtenstein and Thomas Schregenberger suggest, ‘Paolozzi called the source of his fascination a “metamorphosis of rubbish”’ (2001, p. 59), an affirmation of the messiness of everyday life challenging modernist abstract formalism and search for perfection.

From the late 1950s, Ballard would associate with art circles including artist Richard Hamilton; architectural critic Peter Reyner Banham, best known for his sympathetic study of Los Angeles; and Paolozzi himself. So it is no accident that the description of a pavilion similar to Paolozzi's should be found in Ballard's London novel Concrete Island, where the shack built by Proctor, a space of debris enacting the reversal of capitalist society through the apotheosis of its residue, is presented as ‘at least as good as most of the speculative building that's going up these days' (Ballard, 1994a, p. 163). In the autobiography Miracles of Life, reminiscing about his visit to the 1956 exhibition, Ballard foregrounds the striking impression he received from Paolozzi's installation:

Recently I told Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate and a former director of the Whitechapel, that I thought This is Tomorrow was the most important event in the visual arts in Britain until the opening of Tate Modern, and he did not disagree.

[…] Another of the teams brought together the sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi, and the architects Peter and Alison Smithson, who constructed a basic unit of human habitation in what would be left of the world after nuclear war. Their terminal hut, as I thought of it, stood on a patch of sand, on which were laid out the basic implements that modern man would need to survive: a power tool, a bicycle wheel and a pistol. (2008b, pp. 187–88)

In Ballard's works, too, urban dwellings are often, either explicitly or implicitly, post-catastrophic and display a return to primordial conditions. This again is particularly true of the pavilion in Concrete Island, which denotes the same anti-technocratic architectural discourse and the same poetics of found industrial materials which featured so prominently in This Is Tomorrow. This obscure urban landscape of technological debris was regarded by Pop artists as the new natural environment human beings were meant to inhabit while, as artist Joe Tilson writes in his book and print artwork The Software Chart Questionnaire (produced in 1968 and displayed at the Centre for Modern and Contemporary Art in La Spezia, Italy), men and women of the post-war world were ‘the primitives of a new civilisation’.

In Miracles of Life, while reconstructing the encounter with what would become his privileged sources of inspiration—psychoanalysis, surrealism and, to a lesser extent, film—Ballard drops the remark that in the late 1940s he was ‘prone to backing up an argument about existentialism with a raised fist’ (2008b, p. 135). Negligible as it may seem, this passing statement acquires prominence if seen in relation to his later interest in architectural projects influenced by Pop Art. In fact, a major element that inspired the art works of Henderson, Paolozzi and William Turnbull during the late 1940s was precisely the existentialist philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre. In the catalogue of This Is Tomorrow (1956), the definition of architecture as ‘A particle […] snatched from space, rhythmically modulated by membranes dividing it from surrounding chaos’ (Crosby, 1956, sec. 7, n. p.) is clearly symptomatic of this legacy. The existentialist sees the human being as confronting in anxiety the chaotic void into which we are thrown, struggling always to build new islands of being into nothingness. Human beings are not the measure of the world, nor have they the power to enact the law they deem good; rather, we are committed to pulling together whatever can be managed for extreme need and distress. A rickety shack reflecting uncertainty upon itself, the Patio and Pavilion installation evokes a problematic relationship with the chaotic forces of nature, the primitive abode providing only a tenuous protection from the unknown and potentially hostile space outside.

Existentialism was very much in the air at the time; thus it comes as no surprise that Ballard was enticed by its theories. Yet hardly any attention has been paid to the subject (with the notable exception of Roger Luckhurst [1997, pp. 62–69]) and certainly none to how Sartre and Heidegger influenced Ballard's concept of dwelling. Therefore, this will be closely investigated here to reveal the overlapping in Ballard's work of existentialist concerns and responses to contemporary architectural practices and theories. The aim is to disclose the importance for him of the fantasies of bio-technological responsive houses propounded by Archigram, but also to interrogate the imbrications in his fiction of such fantasies with contemporary philosophical ideas of dwelling and unhomeliness. His preference for claustrophobic spaces, even in a novel of compulsive traversals of the city like Crash, calls for a detailed consideration of his concept of habitation before moving on to investigate his depictions of London. Later in the chapter, his views on architectural spaces will be related to both his notion of the body and, notably, his representation of introvert urban forms in Crash, The Drowned World and High-Rise.

In Being and Nothingness, published in French in 1943, Sartre defines dwelling in terms of the accessibility of surrounding objects: ‘To be there is to have to take just one step in order to reach the teapot, to be able to dip the pen in the ink by stretching my arm, to have to turn my back to the window if I want to read without tiring my eyes’ (2003, p. 514). Home is an arbitrary contour: my being-there is a pure given, he argues, a space on hand whose protective isolation is proportionate to the ‘coefficient of utility and of adversity’ (p. 364), and the amount of resistance that surrounding objects offer to the projects of the self. With its narrow confines and tight ring of essential items, Sartre's concept of inhabited space is strikingly reminiscent of Paolozzi's terminal hut (as Ballard defines it) but also of the form of habitation described in the section of Miracles of Life which details Ballard's recollections of his internment in Lunghua Camp during the Second World War: ‘In the G Block a boy […] constructed a cubicle like a beggar's hovel around his narrow bed. This was his private world that he defended fiercely’ (2008b, p. 69). Elsewhere in the text we read: ‘Perhaps the reason why I have lived in the same Shepperton house for nearly fifty years […] is that my small and untidy house reminds me of our family room in Lunghua’ (p. 80). The room to which they were assigned was a broom cupboard; of this space in later life Ballard ‘remembered every scratch, every chip of paint. It was Lunghua, not Amherst Avenue, which felt like home’ (Ballard cited in Baxter, 2011, pp. 103–104). As Heidegger argues in Being and Time published in 1927, ‘“Being” [Sein], as the infinitive of “ich bin” […] signifies “to reside alongside …”, “to be familiar with …”’ (2005, p. 80), while the fundamental aspect of dwelling, as he explains in his 1951 essay ‘Building Dwelling Thinking’ (see Heidegger, 1977, pp. 319–40), is staying with and taking care of things. This care is predicated upon the circle of familiarity (of objects and relationships) constructed out of the estranging chaos and unhomeliness of the world. The line drawn around one's place is what lets things belong to that place and, therefore, be released from the disquieting space outside. Heidegger argues that the phenomenological essence of such a place depends upon the concrete, clearly defined nature of its outer limits, for, as he puts it, ‘A boundary is not that at which something stops, but, as the Greeks recognized, the boundary is that from which something begins its essential unfolding’ (1977, p. 332). Dwelling ‘as “residing alongside …” and “Being familiar with”’ (Heidegger, 2005, p. 233) allows the escape from the anguish of unhomeliness, the indefiniteness of the world into which we are thrown. Yet, for the early Heidegger of Being and Time, it is precisely ‘the existential “mode” of the “not-at-home”’ (p. 233) which constitutes the condition for human beings' recognition of their authentic selves.

This sense of the unhomely as our genuine destiny is one of the elements which compose Ballard's presentation of inhabited spaces, especially in his early fiction. Here characters are often marooned, stranded in the narrow confines of their place where they become committed to the strenuous but futile passive resistance to the chaotic destruction looming over their enclosed space. The surreal short story ‘The Garden of Time’, published in 1962, is emblematic in this connection: the whole story is about waiting for an end felt as inevitable and in the same move its deferral through the taking care of homely things. A ‘high wall […] encircled the estate’, writes Ballard, whereas outside, ‘dull and remote’, the surrounding plain was a ‘drab emptiness emphasising the seclusion and mellow magnificence of the villa’ (2006a, p. 405). While attending to his daily routines and taking care of familiar objects with their comforting ‘presence-at-hand’ (Heidegger, 2005, p. 168), when polishing the pictures in the portrait corridor or tidying his desk, Axel, the protagonist, deceives himself into thinking no threat is impending on the encircled world he shares with his wife. In these moments of oblivion, he lives not, as Heidegger would have it, as ‘the authentic Self’ but as the ‘they-self’, that is, as society prescribes ‘the world and Being-in-the-World which lies closest should be interpreted’; complying with such a prescription ‘brings tranquillized self-assurance—“Being-at-home” with all its obviousness’ (2005, pp. 167 and 233). So, reassuringly ‘shielded by the pavilion on one side and the high garden wall on the other, the villa in the distance, Axel felt composed and secure, the plain with its encroaching multitude a nightmare from which he had safely awakened’ (Ballard, 2006a, pp. 409–10). At other times, though, the couple's existentialist strain seems fully fledged: ‘[his wife's] use of “still” had revealed her own unconscious anticipation of the end’ (p. 409). Anguish is the emotive situation which, for Heidegger, accompanies the attainment of authenticity, because it reveals, in the form of anticipation (a crucial term in Being and Time), our beingfor- death. In Ballard's short story, the advancing throng will soon bring the couple face to face with their genuine destiny: the final triumph of the chaotic world outside is accomplished when the impending inchoate and ‘ceaseless tide of humanity’ (p. 412) finally overcomes the villa.

Ballard's later short story ‘Motel Architecture’, published in 1978, is a further example of existentialist dwelling, but with the notable difference that here the cold, abstract, geometric forms of the modern city apartment are themselves the avatar of our mortal destiny (see Ballard 2006b, pp. 502–30): modernism is an ‘architecture of death’, he asserts in the newspaper article ‘A Handful of Dust’, and in this respect, its style is existentialist (2006a). So the usual connotations of interior and exterior are turned inside out in ‘Motel Architecture’, and the estrangement of Pangborn, the protagonist of the story, is produced by his very enclosure within the confines of his apartment. His alienation is not fled from but fully embraced and probed in search of a more authentic condition: in ‘the immaculate glass and chromium universe of the solarium’, which he has never left over the last twelve years, Pangborn embarks, along with the imaginary intruder haunting his flat, ‘on their rejection of the world and the exploration of their absolute selves’ (Ballard, 2006b, pp. 503 and 512). Finally, it can be argued that in ‘Motel Architecture’, as well as in ‘The Garden of Time’, space and its architectural arrangement are used to express, in fully existentialist terms, the anguished condition of being-in-the-world: this is a potent ontological intuition which will remain subsumed implicitly within the rest of Ballard's production and even in his late London novels of sociological analysis such as Millennium People (2003) and Kingdom Come (2006e).

REGRESSIVE AND RESPONSIVE TECHNOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENTS

With its existentialist transitoriness, Paolozzi's pavilion seemed an ontological reflection on the post-catastrophic environment left by the war and appeared to mark the end of a period, the breaking away from the old theorems of modernism and its megaprojects. However, in continuity with that very modernism, a significant phenomenon was soon to emerge. It was one which, denying this toning down of architectural experimentation, embraced the idol of technology and grasped the new excitement around modern dwelling spaces. In the 1950s the British architectural style of New Brutalism produced a resurgence of ‘creative thought on the certainties of modern architecture, which via Reyner Banham would lead to Cedric Price and Archigram’ (Branzi, 2004, p. 440), an architectural group founded in 1961 and including Warren Chalk, Peter Cook, David Greene, Michael Webb, Dennis Crompton and Ron Herron. These architects operated in the research field of metropolitan utopia, promoting highly technological houses which drew inspiration from the media world. What is striking about their urban projects is that—in contrast with the Situationists' territorial knowledge and appreciation of existing urban environments—all sense of locality is lost, but the idea of place is reintroduced in a regressive guise through the dwelling. This process can be observed in a number of architectural projects such as Cook and Greene's Spray Plastic House Project (1961), a proposal for customized cave-like dwellings formed by excavating spaces from large polystyrene blocks, and Chalk's Capsule Homes (1964), ‘the ultimate in self- existent, conditioned mini-environment with man as extension of machine’ (Greene cited in Steiner, 2009, p. 138). Similarly, Greene's Living Pod (1966; Figure 1.2), where Archigram's curvaceous (organic) vocabulary is particularly prominent, was ‘designed to resemble an organism, complete with inflatable “womb” seat’ (Steiner, 2009, p. 140). Ballard's urban space, especially in the novel Crash (1973), with the car as a narrow habitat, is clearly reminiscent of the claustrophobic, responsive mini-environments experimented by Archigram: the car becomes a mobile dwelling space (‘which may be “worn” for transport and unpacked for occupation’ [Archigram, 2010]) altogether similar to the Cushicle and Suitaloon designed by Webb in 1966–67 as extreme expression of the group's autoenvironment concept.

This interest in the construction of environments that might control psychophysical responses can be found also in some Situationist researches on ambience. In his ‘Formulary for a New Urbanism’ (1953), for example, Debord's Lettrist comrade Ivan Chtcheglov, as Phil Baker reminds us, ‘was at the forefront of the Lettrist interest in the affective environment, and the construction of emotionally determinant ambiences by décor. There would be “rooms more conducive to dreams than any drug, and houses where one cannot help but love”’ (2003, p. 324). Yet, more generally, by placing its emphasis firmly on claustrophobic, introvert spaces, Archigram signalled its distance from Debord's dérive, the ‘transient passage through varied ambiances' ai...