- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Burma

About this book

First published in 2012. Travelling through thousands of miles of Burmese landscape, the author captured the essence of this country before the internal political problems broke. Filled with lively descriptions of Burma - from its bustling cities to its lush jungles - the highlight of the book is the author 's story of his long journey up the Irrawaddy River. Supplemented by the author 's own illustrations, this book conveys Kelly's appreciation of the beauty of the country and the happiness of its people.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

BURMA

CHAPTER I

RANGOON

OUR pleasant voyage was drawing to its close, and there was not one of the passengers of the Bibby liner by which I was travelling but experienced a feeling akin to home-sickness as the time approached for us to bid fare-well to the s.s. Yorkshire, now within a few hours of arriving at Rangoon.

The final match at skittles had been played on the spacious fore-deck, followed by the last of many concerts which, with dances, had from time to time been arranged in order to relieve the “monotony” of a voyage that had not known a tedious moment. Our run out had been uneventfully happy, and the weather perfect.

The last few days’ journey, across the Indian Ocean, accorded well with the spirit of content which pervaded the ship, as, the temperature pleasantly modified by monsoon showers, we would watch the shoals of bonito-driven flying-fish skim its oily undulations, and admire the stately frigate-birds which soared overhead or, regardless of the speedy leviathan which so closely passed them, rested peacefully upon the smooth surface of the ocean.

Yet it was a strange land we were approaching that October morning, and regrets gave place to anticipation as, awaiting our summons from the “bath-wallah,” we lounged about the after-deck in the early dawn and looked for the first appearance of the land. Few of us except the Anglo-Burmans on board had any knowledge of the country we were about to visit, and all looked forward to pleasurable surprises in store with an eagerness hardly tempered by the apprehension of snakes or malaria, which many smoke-room “yarns” told on the voyage might well have engendered.

It must be confessed, however, that my first view of Burma in the grey dawn was distinctly disappointing.

The low alluvial mud banks, scarcely raised above high-water mark, and covered with scrub jungle and “kaing” grass, were certainly not inviting, though those who knew could tell tales of tiger and other large game in these wastes, and of a picturesque life hidden away among the palm groves which dotted the plains.

Entering the river, the turbid waters of the Irrawaddy presented little of interest save a stray catamaran or unlovely Chinese “paddy” boat, and even the picturesquely named “Elephant Point” and “Monkey Point” conveyed little to the new arrival.

Proceeding upstream, however, new growths aroused our interest—cocoa-nut and toddy palms, tamarinds and mangoes, among which the trimly thatched huts of the Burmans or an occasional pagoda furnished the necessary touch of local colour. Nevertheless the scene was tame, and to myself at least disappointing, until, after a couple of hours’ steaming, there suddenly appeared, rosy in the sunshine, the golden dome of the great Shwe Dagon Pagoda, seemingly suspended above the purple haze which still hid Rangoon from sight.

From this moment everything appeared changed, and the freed imagination found possibilities everywhere. Numerous creeks enter the Rangoon river, leading to regions unexplored and mysterious ; from them emerge into the main stream the quaintly shaped boats of the Burmans—strange craft, whose graceful lines and richly carved sterns seem to reflect the minds of a people who love beauty and are content to be happy.

Increasing numbers of steam launches, “paddy”1 boats, and sampans marked our nearer approach to Rangoon, and imaginings gave place to more practical thoughts as the steamer came to an anchor and we prepared to land.

The decks were soon crowded. Native porters, personal servants of returning “Sahibs,” or Eurasian officials, took possession of the steamer and incidentally of anything visible that might perchance be legally claimed as a possible possession of their employers. I must, however, express some surprise at the action of the Customs. Everything in the shape of firearms was at once seized and placed in bond, and in view of the still occasional cases of dacoity such precautions (especially in the case of the .303 rifle) are intelligible and justified ; but why should such palpably innocent impedimenta as “kodaks” or field-glasses come under the same embargo? True, all such belongings were quickly and politely returned at the custom-house in exchange for a simple form of declaration ; but it struck me as a some-what unnecessary and irritating formality, especially to a new arrival all uncertain of his bearings or how to go about things. Otherwise the Customs are easy, and in all cases their officials were polite, even assiduous, in their well-meant attentions.

Half-an-hour after landing found me very comfortably installed in the Strand Hotel, a roomy bed-room with bathroom attached having been allotted to me, while its large enclosed verandah, which practically formed a sitting-room, gave me ample breathing space ; and, making allowance for the latitude, the table-d’hôte was excellent and varied. I was a little disconcerted, however, the first night on retiring, to find that my bed was furnished with mattrass, pillow, and mosquito-net only, no sheet or covering of any kind being provided. I imagined this to be an oversight; but the omission soon explained itself when I found that the thermometer never dropped below ninety-eight degrees all night, and in the damp heat that prevailed it would have been impossible to have endured the weight of even a silk coverlet.

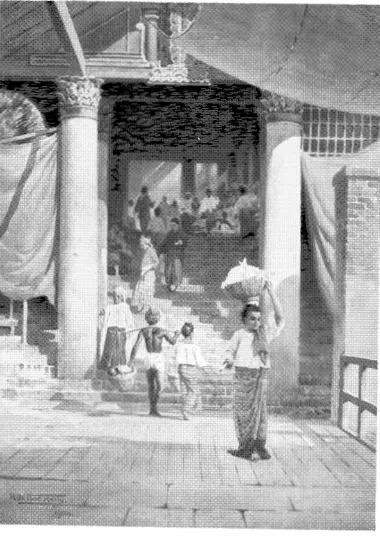

THE PAGODA STEPS, RANGOON

The morning after my arrival I was able to engage a native (Indian) servant, by name Chinnasammy, an excellent “boy” of forty or so, who had served through the Burma war of ’87 as officer’s and mess servant, and who was afterwards to prove of the greatest service to me, as he spoke English and a little Burmese, while I was entirely ignorant of the latter language; and, quite apart from his services as “bearer,” it would have been almost impossible for me, or any one ignorant of Burmese, to have travelled through the country in comfort without the assistance of an interpreter. Even in Rangoon itself, Europeanised though it is, English alone is a broken reed upon which to rely where half the languages of the Asiatic world are spoken, and hardly one of the Eastern races represented has any knowledge of a Western tongue.

Rangoon is interesting—palpably a prosperous and in some ways a handsome city, and is a perfect kaleidoscope of human life.

Built upon the east bank of the river, 30 miles from the sea, it covers an area of 15 square miles, its frontage to the river consisting of excellent quays and “godowns”1 behind which lies the commercial town. The river runs by in deeply swirling eddies, dangerous to life should you accidentally find yourself in the water.

Moored to the wharves, or anchored in midstream, are a surprisingly large number of ocean steamers ; prominent among them are the magnificent steamers of the Bibby line, half-a-dozen or more of the British India Company’s flotilla, and Patrick Henderson and Co.’s latest addition to their fleet. Other ships, steam tugs and lighters, and a multitude of sampans and small sailing craft add to the general effect of bustling commerce, the two principal items of which are impressed upon you by the large quantities of rice husks floating on the water, and the huge teak rafts of the Bombay-Burma Trading Corporation, Steel Brothers, and other merchants, drifting to their destinations at Elephant Point and elsewhere.

On landing, the first impression received is the Indian character of the place, for among all its varied nationalities the Indian native seems to predominate. The dock coolies, in simple loin-cloth and turban, are mostly Madrassees or Chittagonians, the “gharry”1 and “tikka gharry”2 wallahs half-bred Indians, while in the streets, ablaze with coloured costume, the dominant types are Hindus, Tamils, Madrassees, Cingalese, and Chinese. The Burman seems crowded out here, and has evidently been supplanted by his more energetic and active-minded rivals. Even the police in the streets are drawn from that fine body of men the Sikhs, while all the “chuprassies” or Government messengers are natives of India. The Chinese are largely in evidence. Most of the river carrying trade is in their hands ; quite the best shops and houses in the native quarters are theirs ; and their general good-humour and smile of quiet content testify to the prosperity they undoubtedly, and I think deservedly, enjoy. There is, of course, a large Burmese population in Rangoon, but they are mainly to be found in their own quarters, and on the bustling quay-side and business streets are less noticeable than their alien neighbours.

The men (other than Burmans) are on the whole good-looking, and, while the women of Ceylon and India are usually handsome, few of the Burmese women I saw in Rangoon can claim good looks, though quaint costume, beautifully dressed and glossy hair, and general vivacity of manner render them attractive.

Like its population, the town itself is cosmopolitan in style. Many of the more important buildings are fairly imposing, some even good, in architecture, but as a rule they are the square-built stucco houses common to the Levant, and I suppose the East generally, much the worse for wear (no doubt due to monsoon rains), and with the inevitable green “jalousies,” usually rather “wobbly” and badly in need of a coat of paint.

In plan, Rangoon is well laid out. Main streets run parallel with the river front, intersected at right angles by others. These streets are wide and well metalled. Most of them are bordered by trees, an excellent provision in a country whose shade temperature even in the cool season runs up to ninety degrees.

In the centre of the town is Fytche Square, a pretty garden of considerable extent, around which are many banks, merchants’ offices, and the principal shops, the whole being dominated by the beautiful cupola of the Sulay Pagoda.

Among the more important buildings in Rangoon is the new municipal market, an ornate structure of considerable size, and to which the natives have taken kindly, though the bazaars still flourish, and to the artist at any rate offer greater attraction. Many odd nooks and corners of extreme interest are to be found : the Burman and Hindu temples of Pazundoung, the Chinese joss-house at the north end, the shops of the silversmiths and umbrella-makers, as well as the fruit bazaars in the front, while the Chinese and Japanese streets have each their special interest. All this is very fascinating, but is hardly Burmese. In fact, in the streets and bazaars of Rangoon the Burman might almost be regarded as the stranger, and only in the Shwe Dagon Pagoda and a few quarters peculiar to themselves do you find the Burman pure and simple, or at any rate have opportunity for studying him free from the overcrowding, noise, and activity of the other races.

The new-comer is almost immediately struck by the difference between the beasts driven by Burmans and those of other nationalities and religions. The Burmese cattle are always sleek, comfortable, and well fed ; while those of the Mohammedan races are, as a rule, overworked and often cruelly abused. Here, perhaps, is a clue to the reason of the Burman being so completely overshadowed in his own place. Innately gentle, the same instinct and religious obligation which lead him to treat his animals with consideration hardly fit him to compete with the aggressive and noisy cupidity of others, whose one aim would seem to be to extract as much as possible from either man or beast.

Behind the commercial town lie cantonments, the residential districts, the drive out being a very interesting one. All the roads are shaded by avenues of padouk, tamarind, banyan, and palms ; while the gardens, often bordered by hedges of feathery bamboo, are well stocked with tropical growths, among which are many handsome trees and shrubs imported from other countries. Through the hedges may be seen glimpses of flowers and pretty lawns, and the well-built timber bungalows are roomy and often handsome in design. Everywhere are evidences of wealth among the residents, and, by the way, of good government on the part of the municipality, the roads being wide, well kept, and watered, while the public gardens are tastefully laid out and maintained.

The hospitality of Rangoon is proverbial,—my own experience compels me to term it unbounded,—and a few days after my arrival I found myself surrounded by a circle of friends, a member of its leading clubs, and, with my servant, luxuriously installed in the bungalow of a high Government official in the Prome Road, and with all the advantages and opportunities for working which the solicitude of my host was able to afford me. I had been quite comfortable at the hotel, and have often fared worse in tnore pretentious establishments nearer home ; there is, however, this disadvantage in living in “town,” that your environment is entirely the business element, which is so largely composed of alien races that “Burma” is eliminated from your view. Living in cantonments, however, with its purer air and more reposeful conditions, was very pleasant and the day’s work relatively easy, while the Burman proved more easily discoverable than in the commercial centre, and at the same time under conditions which better suited his temperament. As the roads in the suburbs are well wooded and pleasant for promenading, here and in Cantonment Gardens, as well as the public parks, the Burmese lady, gay in coloured silks, is fond of walking with her no less daintily clad children. In the neighborhood are many Burmese villages with their quaintly carved “kyaungs”1 and “zeyats”2 ; but above all you are in close proximity to that wonderful building, the central and most sacred shrine of Buddhism, not only in Rangoon but throughout the country, the great Shwe Dagon Pagoda.

Here at last you find the Burman in his purity, and amid surroundings which are entirely complimentary, and much of my time in Rangoon was spent upon its platform, charmed but bewildered.

I find it increasingly difficult to give any adequate idea of this marvellous building, which Edwin Arnold fitly describes as a “pyramid of fire.” It is simply wonderful, and impossible of description. As, however, this, the greatest of all Burmese pagodas, is but a glorified example of the rest, I must make the almost impossible attempt to describe it.

First let me say that there are two principal form...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Chapter I Rangoon

- Chapter II Amenities of Rangoon

- Chapter III Across the Yomas to Taungdwingyi

- Chapter IV Life in a Burmese Market Town

- Chapter V Jungle Life at Kokogon

- Chapter VI Through the Forest to Pyinmana

- Chapter VII One Thousand Miles up the Irrawaddy : Part I. (Rangoon to Prome)

- Chapter VIII One Thousand Miles up the Irrawaddy : Part II. (Prome to Bhamo)

- Chapter IX Two Capitals

- Chapter X Some other Towns

- Chapter XI A Month on the Lashio Line

- Chapter XII Camping in the Northern Shan States

- Chapter XIII The Burman

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Burma by R. Talbot Kelly,Kelly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.