- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Qualifying Associations

About this book

This is Volume XII of eighteen in a series on the Sociology of Work and Organisation. First published in 1964, this study looks at one important aspect of professionalism, the way to professional status through organization. It describes the Qualifying Association, a type of organization which attempts to qualify individuals for practice in a particular occupation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

PROFESSIONS, PROFESSIONALIZATION AND PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATION

THE PROBLEMS OF DEFINING A PROFESSION

OF all sociological ideas, one of the most difficult to analyse satisfactorily is the concept of a profession. Perhaps three basic problems account for the confusion and uncertainty. Firstly, there is the semantic confusion, resulting from wide and excessive use of the word. Secondly, there are the structural limitations enforced by attempts to devise fundamental characteristics of a profession. Thirdly, there is the adherence to a static model, rather than an appreciation of the dynamic process involved in professionalism.

Semantic Confusion

Concepts such as family, status, class, and morals have also become confused through popular and often misguided use, but at least these have attained some sociological stability. ‘Profession’, ‘professionalism’ and ‘professionalization’ have been less fortunate.

In popular usage, ‘profession’ and ‘professional’ appear to have a variety of meanings. Thus, the word ‘profession’ may be used as a polite synonym for ‘job’, ‘work’, ‘occupation’. The question ‘What is your profession?’ may really be considered, by the inquirer, as a genteel form of ‘What's your job?’. Alternatively, the description is applied to anyone neatly dressed, who does not apparently wear special clothing for work, and who is concerned with clerical operations. So the term becomes attached indiscriminately to any, and every, type of ‘black-coated’ and ‘white-collar’ occupation. A further source of trouble arises from the difference between ‘professional’ and ‘amateur’, used in sport and leisure time activities. Here, the amateur is one who performs certain tasks, on a part-time basis, for the intrinsic pleasure obtained from them, and not for any financial reward or profit. The professional regards the same process as a full-time occupation, providing the main income. Another connotation of ‘professional’ implies the successful completion of a task with great skill. The results are indistinguishable from those obtained by using skilled personnel, who consider that type of work as their major occupational activity.

A second form of semantic confusion comes from the addition of prefixes and qualifying words. Numerous versions have been developed—for example, pseudo-, semi-, quasi-, sub-, auxiliary, marginal, liberal, learned. Only some expressions have assumed any extensive use. Often, the origins are impossible to trace, because the term is employed without definition, suggesting that the reader already knows the true meaning and value. Many times, the intention is to derogate attempts, by members of an occupation, to establish professional status for themselves. Those struggling are judged to be unworthy of the classification. Sometimes the addition is helpful. Sometimes the description is official. But on most occasions, the real aim is to escape the thought that all professions are equal. Differences, it is felt, must separate professions from non-professions, new from old, acceptable from unacceptable. If anything, these represent strivings toward a definition, and the characteristics distinguishing a profession from other occupations, without resorting to an actual definition.

Thirdly, confusion arises from the indiscriminate use of the term ‘profession’ to describe dissimilar concepts. As M, L. Cogan1 points out, ‘profession’ is employed (a) to differentiate one occupation from another, (b) to designate a formal vocational association, (c) to describe a licensed vocation. In a later paper,2 Cogan suggests that confusion arises from three levels of definition: (a) a historical and lexicological definition, (b) a persuasive definition, attempting to redirect attitudes, (c) an operational definition, offering a basis of guidance for the professional. This analysis is less helpful. Few definitions fit easily into one of these three classifications; sometimes the best category cannot be determined. In fact, most definitions contain up to three parts: (a) a historical element based on the traditional professions, (b) an idealistic element to act as an incentive, (c) a realistic element relating ideal and tradition to current form and practice.

Finally, confusion arises from an incomplete, or a mistaken, image of an occupation. For example, the description ‘engineer’ is applied to anyone from a lathe-setter, to a trained and qualified technical expert. A librarian is a person who issues tickets and stamps books, in a public lending library. Little difference would be seen between an insurance underwriter and an insurance agent, who collects small premiums from door to door. A pharmacist is described as a ‘chemist’, although a chemist really performs a different function.

Structural Limitations

In order to define and delimit occupations to be considered as professions, various writers have offered the characteristics of a profession. Such aids suffer from disabilities.

Firstly, the authors begin as historians, accountants, lawyers, economists, engineers, philosophers, sociologists, etc. As a result, group affiliations and roles determine the choice of items, and bias. Usually, the measures are presented with their own occupations in mind. The lawyer emphasizes the fiduciary nature of the professional-client relationship, the depth of learning, the cordial colleague relationships and sense of public service.3 The accountant may stress the organized control over competence and integrity, the value of practical experience and so on.4

Secondly, the influences of one author upon another can be traced. In the end, too few would seem to have actually considered the problem afresh. Many rely upon the same formulae, containing slight additions. Carr-Saunders and Wilson is the classic study, from which most authors have taken their postulates.5 The Webb's survey6 and the passionate aside of R. H. Tawney7 also provide starting points.

Thirdly, characteristics and definitions have been moulded to fit arguments. More accurately, special characteristics have emerged from special considerations. For example, Tawney attacks the functionless property derived from the capitalist system of industry, and suggests the subordination of industry to the community's needs. To reform industry, he proposes changes, which rest on a comparison of industry and the professions. Professions are organized for the performance of duties. Similarly, industry must aim to serve. Herbert Spencer's idea of a profession is strikingly unusual, yet this view flows from an organic theory of society.8 Considering society as an organism, its members are subservient to the necessary functions to be performed. Groups within society are responsible for various functions—defence, the regulation and sustenance of life. Professions carry out a further general function: the augmentation of life. By curing disease, removing pain, etc., medical men increase life. Musicians and dancers ‘exalt the emotions’ and increase life … and so on, through poets, dramatists, authors, scientists and philosophers. Emile Durkheim's viewpoint develops from his belief in the trend toward, and growth of, group solidarity within society.9

Consequently, a mass of confusion stems from all analyses, which attempt to determine the occupational characteristics of a profession. Individual bias results from a strong occupational, or theoretical, outlook. Ready adoption of a few premises, from other people, has led to sterility. A further complication appears when authors speak in terms of ideals, either to spur on fellow practitioners, or to re-inforce their feeling of achievement.

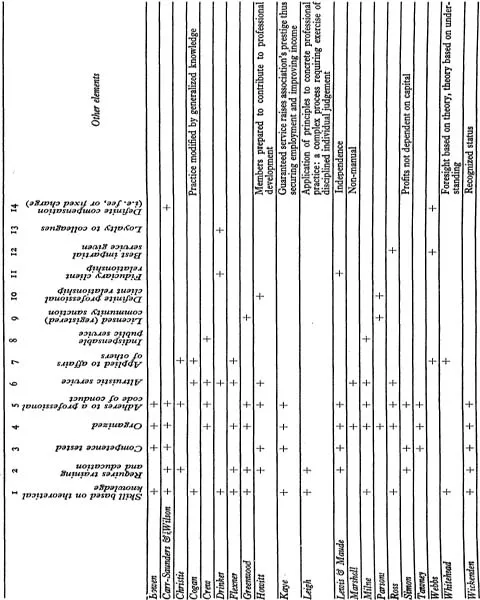

Table 1.1 presents an analysis of characteristics put forward by a number of different commentators. Prevalence of particular aspects perhaps implies agreement, as well as blind acceptance from others. Interesting ornamentations occur outside the central theme.

Essential features expressed here are:

(a) A profession involves a skill based on theoretical knowledge.

(b) The skill requires training and education.

(c) The professional must demonstrate competence by passing a test.

(d) Integrity is maintained by adherence to a code of conduct.

(e) The service is for the public good.

(f) The profession is organized.

TABLE 1.1. SHOWING AN ANALYSIS OF ELEMENTS INCLUDED IN VARIOUS DEFINITIONS OF PROFESSION

For references to sources see (10) in “Notes to Chapter One” at end

Constantly underlying definitions, there are various sentiments. For example, the professional is a noble, independent individual who places public duty and honour before all else. But neither the characteristics presented, nor the sentiments commonly supporting them, allow a realistic assessment of the professional situation. While some characteristics seem reasonable and realistic, others appear restrictive. Must a profession be organized? Must a professional pass an examination to show competence? Is a code of professional conduct always necessary to enforce integrity? Do professionals always operate a valuable public service? How many professionals are actually independent practitioners? These questions expose the third fundamental problem in defining a profession.

Dynamic Realism

Based on the first professions of the church, law and medicine, a traditional image of the professional evolved. He was a ‘gentleman’, an independent practitioner dispensing a necessary public service of a fiduciary nature. His competence was determined by examination and licence. His integrity was ensured by observance of a strict ethical code. Unprofessional conduct could lead to complete deprivation from further practice. His training and education were institutionalized. Here was the model for all professions. Several criticisms might be made of this ‘image’.

Firstly, the respectability of these professions, as a whole, only emerged in the eighteenth century, to be consolidated in Victorian England. Secondly, compulsory tests of competence were applied to these professions at a comparatively late date. Barristers were not subjected to a compulsory examination until 1872. Solicitors were examined from 1836. Medical practice was without regulation until 1858. Qualifications were not required for practice; and existing degrees and diplomas varied considerably in standard. Before the 1850s, no serious test was generally imposed prior to ordination. Thirdly, high prestige of these professions resulted from other elements besides control over the profession, and the vital nature of the service, (a) Practitioners became heavily involved in local affairs—government, justice, education, local banks, etc. (b) The legal and medical professions furnished valuable means of social mobility. Those from humble origins tended to stress their respectability.

As founded upon the traditional structure and work of law, medicine and the church, the professional ideal remains unsound. First, the majority of professionals are no longer independent practitioners, working by themselves. Over the last hundred years, the tendency has been for independent professionals to decline in number and proportion, even in the older professions.11 Of course, some professions seem likely to contain a higher proportion of independent practitioners, either due to the nature of the work, or through special restrictions preventing partnerships and group practice. Second, not all professionals are involved in a direct, personal, fiduciary client-professional relationship. The close, confidential, single-client relationship found in legal, medical and spiritual matters, has a particular quality peculiar to those professions. Though confidential matters, concerning person and property, arise in many occupations, these are not quite the same. A strict, ethical code is not automatically required to protect public and professionals, in every type of professional service. Third, the mere formation of an organization, to certificate members and control professional conduct, does not immediately entitle the occupation to be designated as a profession. Fourth, a false impression is given of professional remuneration. While lawye...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Tables

- Charts

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Professions, Professionalization and Professional Organization

- 2. Types of Professional Organization

- 3. Why Are Qualifying Associations Formed?

- 4. Structure of Qualifying Associations

- 5 Qualifying Associations and Education

- 6. Qualifying Associations and Professional Conduct

- 7 The Qualifying Association In Society

- 8 Conclusion

- Appendix I: A List of Qualifying Associations in England and Wales

- Appendix II: Chronological List of Existing Qualifying and Non-Qualifying Associations in England and Wales

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Qualifying Associations by Geoffrey Millerson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.