- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Juvenile Delinquency in an English Middle Town

About this book

This is Volume XI of fifteen in a series on the Sociology of Law and Criminology. First published in 1948, the local enquiry which forms the backbone of the present book may be regarded as a sequel to two other investigations: to the Home Office Enquiry into Juvenile Delinquency, undertaken at the London School of Economics, the results of which were published in 1942 under the title Young Offenders, by A. M. Carr-Saunders, H. Mannheim, and E. C. Rhodes, on the one hand, and to the Cambridge Evacuation Survey, published in 1941 under the editorship of Susan Isaacs with the co-operation of Sibyl Clement Brown and Robert H.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Juvenile Delinquency in an English Middle Town by Hermann Mannheim in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter I

The General Setting

JUVENILE DELINQUENCY IN AN ENGLISH MIDDLETOWN (CAMBRIDGE)

5. WHEN the Lynds set out to find a suitable object for their study of life in an American "Middletown",1 they made their selection according to a number of characteristics which they regarded as particularly desirable, such as, for instance, a size of 25-50,000 inhabitants, a small negro and foreign-born population, not a satellite town, and other positive and negative criteria. While fully realizing that, strictly speaking, a typical town, just as a typical individual, does not exist, the Lynds believed to have found a place which possessed, at least comparatively speaking, the highest possible number of characteristics common to a large group of American communities. For the present investigation, Cambridge was chosen, not according to any preconceived ideas as the prototype of a certain category of English towns, but simply because it had granted hospitality to the London School of Economics during the whole of the last war and was, therefore, the most convenient object of study. According to the standards applied by the two distinguished American sociologists, it is for very obvious reasons certainly not a typical "Middletown". When the Lynds, several years after the completion of their original survey, returned to the scene of their studies and discovered that "Middletown" had meanwhile become a "college town", they found it necessary to declare with some emphasis that, had this feature already been noticeable in 1923 when the choice was first made, the town would not have been selected for study1. Which seems to indicate that the presence even of such a comparatively modest institution for higher education as that college with its "nearly a thousand students" apparently presented itself in 1936 destroys any claim of the community concerned to be regarded as a "Middletown". How much more would this be true, in the eyes of the Lynds, of a town which is the seat of one of the oldest and most famous Universities in the world.

The undiluted commonplace character of "Middletown" made it possible for the Lynds to try, with at least some prospect of success, to conceal its identity. In view of the very detailed discussion of each and every aspect of local life in their book, such anonymity appeared desirable to the investigators. How far their aim has actually been achieved may be open to doubt; it must, in fact, have been fairly easy for every interested person in the U.S.A. to find out the model of that famous study. In the case of Cambridge, anonymity would have been a mere farce unless all the most characteristic local features had been entirely suppressed. Moreover, as our investigation had to be of a much more restricted and cursory nature than "Middletown", the whole issue was bound to become one of minor importance only.

6. In spite of its many atypical features Cambridge has, however, to a surprising extent still preserved the atmosphere of a quiet country town situated in the heart of a predominantly agricultural district and seemingly very remote from the turmoil of the capital, fifty miles away.

There exists, unfortunately, no comprehensive social survey or other recent publication to be used as a guide to the study of the social structure of Cambridge, which ought to form the background for this enquiry. Nothing more up-to-date has become known to the author in this respect than Miss Eglantyne Jebb's book Cambridge: A brief study in social questions1, which, though a thorough and well-balanced piece of work, must necessarily have become obsolete in the nearly forty years since its publication. To quote a few facts from it might, nevertheless, not be out of place, in order to compare local conditions at the time when Miss Jebb wrote and present conditions, and to show the trend of developments.

Population. In the hundred years between 1801 and 1901, the population of the Borough had grown from 9,276 to 38,329, and the number of inhabited houses from 1,691 to 8,700. "Side by side with the beautiful medieval city, so dear to the hearts of successive generations of Englishmen", writes Miss Jebb, "another town has grown up, one with a population four times as great and covering a much larger area. ... A people habituated for hundreds of years to country life has had to adapt itself to a new environment and to new habits of life. It was impossible that the new town should spring up without the danger of grave evils accompanying its growth".

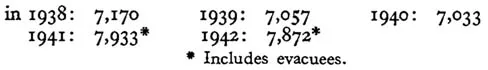

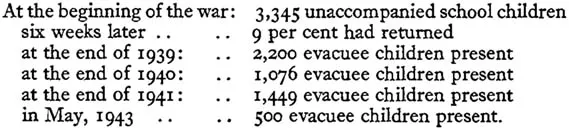

Since this was written, the population has further grown to 66,789 according to the census of 1931, and to an estimated figure of 76,760 in 1936 and of 81,383 in 1940. The last-mentioned increases were partly due to the provisions of the Cambridge (Extension) Order, 1934, which gave the Borough a considerable increase in area to a total of 10,000 acres with an estimated number of 20,173 inhabited houses1. The last war, too, contributed to this upward trend through the influx of thousands of war workers and evacuees. Owing to the frequent changes in their numbers, accurate figures are not available for these two categories, except for evacuee children of school age. Whereas the local elementary school population numbered2:—

the following figures3 may show the fluctuations in the number of evacuee children on the School Register:

In view of their uncontrollable comings and goings, due mainly to the changing intensity of air raids, no exact data for the intervening periods could be obtained4.

7. Industries. In his brief but well-informed summary of "The Industries of Cambridgeshire5, Dr. F. M. Page quotes Daniel Defoe's dictum, in Tour through England and Wales (1724-26): "this county has no manufacture at all". Even right up to the last war, as Dr. Page points out, industry occupied only a subsidiary place in and around Cambridge. Nevertheless, there have been a number of industries in existence—some of them for many centuries, others of more modern growth—such as brick and tile works, cement works, printing, scientific instrument making, radio, brush making and, in particular, fruit preserving. Especially, the well-known jam factory of Messrs. Chivers & Sons in Histon, with between 2,000 and 3,000 employees, and the Cambridge Instrument Company with about 700 employees (these figures refer to 1938) have become important features of local life. With these exceptions, however, agriculture and the colleges appear almost completely to have dominated the picture.

Here, as in so many quiet non-industrial areas of the country, the second World War brought about very considerable changes. Aerodromes and munition factories sprang up in the neighbourhood and gave employment to the townspeople and to thousands of workers from other districts. Members of the armed forces—British, Dominion, American, Polish, and others—were stationed in or around Cambridge in considerable numbers, and there was also a large camp with Italian prisoners-of-war. Several colleges of London University with some thousands of students, evacuated either for the duration or at least for the first years of the war, made up for the loss of local undergraduates. As a result, Cambridge boys and girls were not only offered a much wider choice of jobs than ever before, they were also brought into close contact with people whom they would hardly have met in peace-time, and had to face temptations which their parents had never experienced. On the other hand, certain factors which constituted especially grave dangers to juvenile morale in London and other badly-bombed cities—such as prolonged shelter life, opportunities for looting, demolition work and the like—were almost entirely absent, as Cambridge had very few serious air-raids and the shelters were not much used.

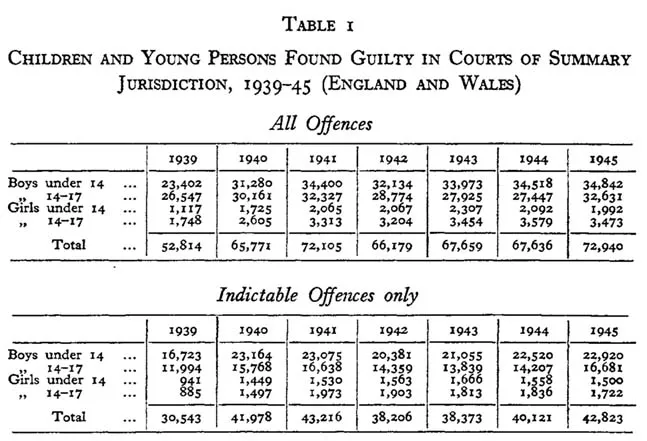

8. Compared with the figures for the whole of England and Wales, as given by the Home Secretary in the House of Commons1 and reproduced below (Table I), the curve for Cambridge is, generally speaking, in accordance with the universal tendency (see Table 2). In both cases, we find a jump from 1939 to 1940 and, after a decline in 1941 or 1942, another jump in 1945. The increase is, however, much more marked in Cambridge, the year 1940 showing a plus of more than 50 per cent, as against over 20 per cent, for the whole country, and the year 1945 even one of 80 per cent, as against less than 40 per cent. for the whole country. Although, as pointed out below, no exact information is available on this point, it is obvious that the 1940 increase was, to some extent, due to the influx of evacuee children from London to Cambridge. As many as nine of the twenty evacuees whose cases are mentioned below (paragraphs 35-36) had appeared in Court in the course of the year 1940, and seven in 1941. In 1945, however, when the highest increase occurred, almost all these evacuees had gone home, and other explanations will have to be found.

For the three pre-war years 1934, 1935, 1936, the average figure of indictable offences committed by juveniles in Cambridge was given by Dr. E. C. Rhodes as 0.38 per 1,000 of the population.1 On the basis of a wartime population of 80,000, the average for the five years 1941 to 1945 is, according to Table 2, 0.76, i.e. exactly twice the prewar average.

On the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Tables

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter I The General Setting

- Chapter 2 Analysis of a Sample of Pre-War and Wartime Probation and Supervision Cases

- Chapter 3 Methods of Treatment Used by the Juvenile Court

- Chapter 4 Some Special Problems

- Chapter V Principal Findings, General Conclusions and Recommendations

- Bibliography

- Index of Persons

- Index of Subjects