- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1997. Information processing is crucial to social life and an important element of control. Innovations in information processing have the potential to dramatically alter social relations. Understanding the process of technology innovation and diffusion as well as the economic, social, political and cultural impact of a diffusing/diffused technology is crucial to understanding society as technology is often the impetus for social change. This book addresses both the process and impact of technology innovation as it relates to communication technology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Telegraph by Annteresa Lubrano in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Telegraph

Part One

I

Origin and Diffusion of New Technology

Technology innovation is a process in which origin and diffusion are two of the major elements. Innovation implies change; embedded in the concept of social change is the question of the origin and diffusion of new technologies. Various academic disciplines have developed models to account for this process. This chapter will examine these models in relation to telegraph technology and within a sociological framework. Each of these models focuses on the diffusion process and tries to explain the S-shaped curve that usually results from plotting diffusion rates, primarily in terms of a single variable, for example, profit cycle or adopter characteristics. Each model works well for the particular kinds of technology that it deals with. However, the needs and nature of interpersonal communication technology do not make it amenable to any of the existing models. Consequently, an alternative model of technology diffusion is offered that is specific to interpersonal communication technology and which encompasses multiple variables as essential to driving the diffusion process.

Origin of new Technologies

Invention generally refers to the initial discovery of something new. Innovation is an activity. It introduces invention into the social structure, whether it be a new method for performing a task, a new custom, or a new product/device/service. Various theories have been put forth to account for the origin of inventions/innovations. Parker (1974: 36) posits three theories for invention:

Transcendentalist theory—gives primacy of place to individual genius. In this theory, the lone inventor makes a great impact with a single creative thought.

Mechanistic theory—invention is the offspring of necessity; need dictates and technology complies. In this theory economic forces predominate and the role of the individual genius is rejected.

Cumulative Synthesis theory—asserts that invention arises out of the accumulation of knowledge. Insight is required (this is where the individual plays a role) but one person’s work is inseparable from the work of his/her predecessors.

Transcendental and cumulative synthesis theory both seek to stress human agency in the invention process. Both place the source of invention within the individual, though from dialectically opposed points of view. Mechanistic theory seeks to locate the source of invention within the economic institution of society. In this view, human beings are tools of the economic order. It is the needs of the economy, not merely the creativity and intellect of human beings (or collections of human beings), that drives the innovative force. It is not the human endeavor of gaining increasing control over life that dominates, but the survival and proliferation needs of the economic system that dominate. The theories Parker presents can be used as a framework within which to view the work of other researchers on the origin of new technologies.

Transcendentalist versus Cumulative Synthesis Theory

The opposition of these two theories represents the classic debate concerning the origin of new technology. Though the specific labels may change, the central question remains the same: Is innovation the result of individual genius, or is it the result of insight applied to a culture’s accumulated store of knowledge? There is a strong temptation within American culture to recognize individual genius as this is in keeping with one of the basic values of American Culture—individualism. Deeply rooted in our culture is the belief that success or failure is primarily within the control of the individual due to his/her characteristics, abilities, and motivation. Consequently, formal recognition for achievement is necessary as a hallmark of success. We are not a society oriented to collectivism and thus theories of the cumulative synthesis nature are not emphasized in our history books but do bear examining if we are to acquire a full understanding of the innovation process.

Singletons and Multiples

Merton’s (1974) work falls under the cumulative synthesis theories. Merton addresses the question of the origin of innovations and frames it in terms of the battle between the social determination theory of discovery (that is, that the course of science and technology is a continuing process of cumulative growth) and the heroic theory (that is, the result of men of genius, who, with their ancillaries, bring about basic advances). Merton posits that we are often misled into believing that individuals are responsible for scientific innovation because of the practice of eponymy. He offers as examples Boyle’s Law and Planck’s Constant, and one could easily think of other examples. Merton (1974: 215) writes that this practice leads to “the virtual anonymity of the lesser breed of scientists whose work may be indispensable for the accumulation of scientific knowledge—these and similar circumstances may all reinforce an emphasis on the great men of science and a neglect of the social and cultural contexts which have significantly aided or hindered their achievements.” In the dynamic view of innovation origin and diffusion, innovation comes about due to the work of various scientists, their ability to draw from the accumulative culture, as well as from social need. Citing the work of William F. Ogburn and Dorothy S. Thomas concerning the multiple and independent appearance of the same scientific discovery, Merton (1974) concludes that such innovations became virtually inevitable as certain types of knowledge accumulated in the cultural heritage, and, as social needs diverted attention to particular problems. Consequently, one can conclude that the confluence of these events will lead to the multiple and independent appearance of a scientific innovation. Merton (1974: 356) states that “the pattern of independent and multiple discoveries in science is in principle the dominant pattern rather than a subsidiary one. It is the singletons—discoveries made only once in the history of science—that are the residual cases, requiring special explanation.”

Both Parker and Merton agree that the lone inventor theories are not adequate to explain invention and innovation. They see theories that account for the dynamics of need and accumulated culture as providing a more accurate picture. Telegraphic history can serve as an example in support of the cumulative synthesis type theories, and Merton’s theory of multiple invention in particular.

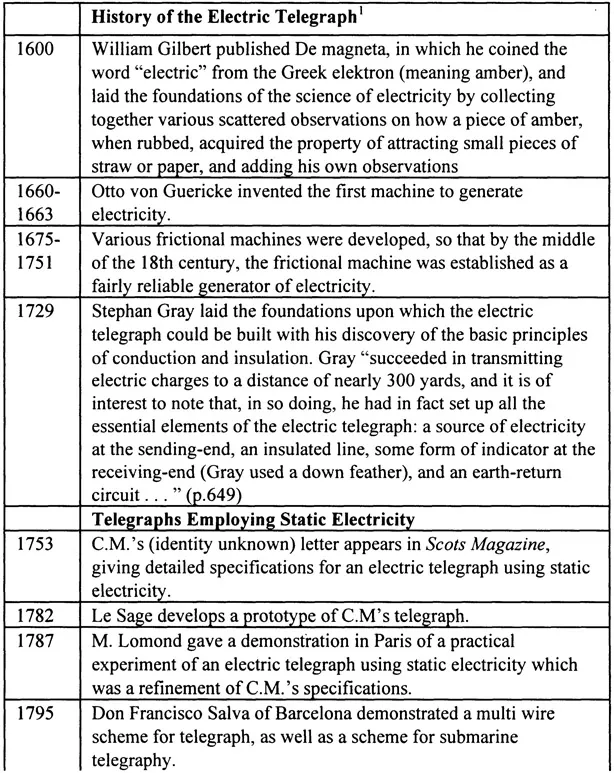

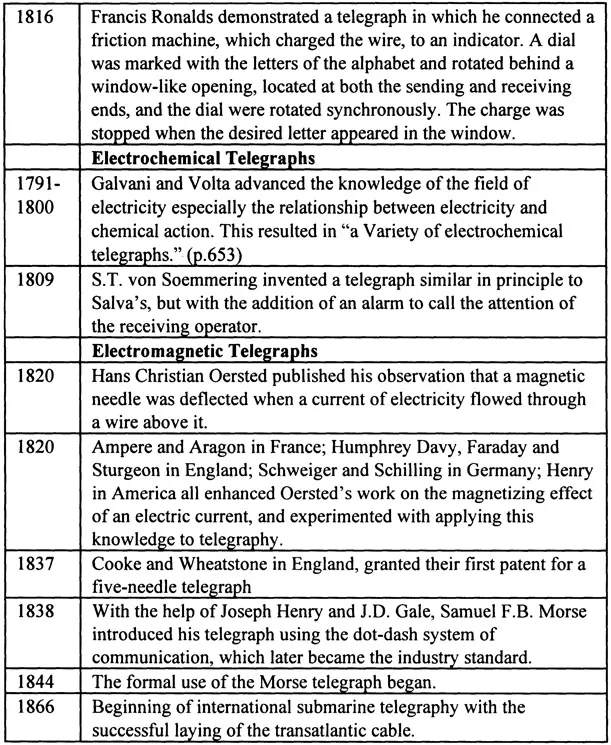

The discovery of electricity was the innovation which would ultimately lead to the first modem innovation in communication technology. This knowledge became part of the accumulative cultural base of many Western European countries (as well as America after its settlement) and men of science all around the world, were searching for a way to apply electricity to communication. They were addressing the problem of how to send electrical impulses through wire. George Louis Le Sage, Francis Ronalds and others experimented with lines to conduct electricity. They needed the work of Galvani, Volta, Oersted and Ampere before science had the practical knowledge to apply electricity to long distance. It was the combined work of Arago, Sturgeon, Steinheil, Weber, and other European scientists that Samuel Morse built upon to “invent” his electro-magnetic telegraph. (Much scientific knowledge was shared through the papers scientists published, as well as through informal, salon-type discussions). Though the groundwork for the invention of the telegraph was well laid, no telegraph proper (that is, no instrument that could “write” messages at a distance) had been invented until Morse did so. Another similar device was developed around the same time (1830’s) by the Englishmen Cooke and Wheatstone. Their telegraph operated on a different principle from Morse’s—it did not leave a written record, but it does help to explain how England had an operating telegraph only shortly after the United States. Table 1-1 depicts a history of the electric telegraph and clearly illustrates two important facts: that though Morse’s name is most closely associated with the discovery of the telegraph in America, the same discovery was independently and simultaneously being made in England; the invention of the telegraph was the product of an accumulated store of knowledge. The previous discoveries of other scientists were of crucial importance. The dissemination of knowledge and its incorporation into the cultural base are important components for the multiple and independent discovery hypothesis. It should be noted however, that the very dissemination and incorporation of such knowledge brought about one of the earliest fights over “intellectual property” rights. A discussion of the impact of this argument can be found in chapter 7 in the section on patent law. The words of Dronysius Lardner (1855: preface) seem apropos here: “The Electric Telegraph is not the invention of an individual … it is the joint production of many eminent scientific men and distinguished artists of various countries, whose labours and experimental researches on the subject have spread over the last twenty years.”

Telephone technology has a similar history of simultaneous development, only in this case, the simultaneous discovery was by two Americans. Both Alexander Graham Bell and Elisha Gray “invented” the telephone. Both filed for patents on their telephone devices on February 14, 1876. Building upon the work of other scientists, and driven by the desire to transmit sound over the telegraph wires (but for different reasons—Bell was seeking to aid the deaf, Gray to transmit music), both men discovered a means by which human voices could be transmitted over the wires. In addition to the work of the scientists who contributed to the invention of the telegraph, the work of Herman Von Hemholtz, Thomas Edison, and the researchers at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology was crucial to the invention of the telephone.2 Again we see that invention was the product of need and insight applied to accumulated knowledge.

Telegraph and telephone technology are two illustrations of Merton’s theory of multiple invention as the result of social need and accumulated cultural knowledge. However, each highlights a different aspect of the idea of social need. Telegraph innovation grew out of the general need for greater control over information processing, and was made possible by Morse as well as Cooke and Wheatstone as they built upon the knowledge available in their respective cultural heritage’s. Telephone innovation is an example of innovation growing out of a more particular sense of need, for example, Bell’s desire to aid the deaf. Though Bell’s invention didn’t satisfy the particular need he was driven by, it does illustrate how social attention can be focused on an area of study (that is, the instantaneous transmission of information) which leads to varied inventions.

Table 1-1. History of the Electric Telegraph

Mechanistic Theory

Mechanistic theory gives primacy of place to economic factors. The language and framework of mechanistic theory is that of the economists. Technology is the response to market demand whether it be industry driven or consumer driven.

Push/Pull Economic Theory

A specific application of the mechanistic theory of invention is push/pull economic theory. According to this theory, the sources of innovational pressure are dichotomized as: push—innovation as the result of the initiatives of research and pull—innovation as the result of the expression of customer/consumer need. Using the history of early telegraphic technology in Europe as an example we can illustrate the “pull” aspect of this theory. The immediate predecessor of the electric telegraph was the optical telegraph, or semaphore. This telegraph was invented by Claude Chappe, a Frenchman, in 1794. Chappe wanted to devise a system of communication that would enable the central government to receive and transmit intelligence information and orders in the quickest possible time. The French government, at war with most of its neighbors, adopted this form of communication during the French Revolution. The expansion of the telegraph system in France continued even after Napoleon seized power in 1799. By 1844, France had 533 stations and 5,000 kilometers of line. The semaphore system that Chappe invented eventually spread all over Europe. The British developed their own version of the telegraph after noticing the way the French were communicating, and after finding a drawing of Chappe’s telegraph they set out to produce a better system. Garratt (1967: 646) posits “In England, reports of the working of the Chappe line between Lille and Paris were received during the autumn of 1794, and an illustrated description appeared in The Sun on the 15 of November. Although it was not uncommon for similar inventions to be made quite independently yet simultaneously in widely different places, it seems likely that it was those reports from France that stimulated Lord George Murray and John Gamble to propose schemes for visual telegraph systems to the Admiralty in 1795.” In the late 1790’s Britain built telegraph lines all along its coast. Among the other European countries, Sweden was quickest to set up a telegraphy system of their own in 1795 due largely to the work of Abraham Edelcrantz. The Germans had a primitive form of the semaphore in 1798, and Denmark had a modified form by 1802.3 However, when military need ebbed, the optical telegraphs tended to be abandoned because they required extensive manpower and expense to operate. Stations were seldom more than eight miles apart and were subject to interruption due to adverse weather conditions. These systems were of little use to the individual citizen or to the business community in Europe at the time.

This example of “pull” theory illustrates an important point in relation to the innovation process. Technology that is developed in response to a particular need has a guaranteed pool of potential adopters and is therefore more likely to display a quicker beginning in the diffusion phase of the innovation process as seen in relation to the shape of the S-curve.

Transcendental Theory Versus Cumulative Synthesis and Mechanistic Theory

Cumulative synthesis theory and mechanistic theory are not incompatible. They can work in concert with each other when one examines the origin of innovation from an organizational perspective. What emerges from this perspective is a conflict between the idea of the lone individual inventor versus innovation as the offspring of formal research and development departments within formal organizations.

Individual Versus Research and Development Within Organizations

The controversy between heroic and cumulative synthesis theories can be cast in yet another form—individual research versus research and development within and organization (transcendental theory vs. cumulative synthesis and mechanistic theory). According to this debate, the individual inventor, motivated by dreams of personal acclaim and financial success, is thought to be the driving force behind innovation. Conversely, the opposition view states posits that it is the accumulated knowledge within the formal research and development departments of organizations that is the driving force behind innovation, motivated by economic need. Research can be found to support both positions. For example, in support of the independent inventor is the work of Charpie (1970) who informs us that among industrialized economies 30%-5...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Tables and Figures

- Preface

- Introduction

- Acknowledgments

- Part One

- Part Two

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index