![]()

| 1 |

Historical Approaches to Natural-Resource Scarcity |

The focus of this chapter is the historical development of economic theories of natural-resource scarcity, from Adam Smith and the classical economics through to the landmark 1963 study by Barnett and Morse, and the contemporary conventional view. These theories have traditionally been classified as either “pessimistic Malthusian” models that suggest a long-term absolute natural-resource scarcity constraint or “optimistic Ricardian” models that do not assume any absolute limits but only admit that resources decline in quality and are therefore relatively scarce. The major themes of this chapter are, first, to examine how well these Ricardian and Malthusian labels fit the classical and neo-classical theories of natural-resource scarcity, tod secondly, to demonstrate how adoption of the Ricardian perspective on resource availability allowed more modern theories to become increasingly sanguine about the ability of market forces and technological change to overcome any “relativ” scarcity.

MALTHUSIAN AND RICARDIAN SCARCITY

Barnett and Morse are often credited with being the first to draw a distinction between Malthusian and Ricardian economic approaches to natural-resource scarcity.1 In making this distinction, the authors laid the groundwork for the differentiation between “absolute” and “relative” scarcity, with the former being associated with Malthusian and the latter with Ricardian scarcity:

Modern views concerning the influence of natural resources on economic growth are variations on the scarcity doctrine developed by Thomas Malthus and David Ricardo in the first quarter of the nineteenth century and elaborated later by John Stuart Mill. There were two basic versions of this doctrine. One, the Malthusian, rested on the assumption that the stock of agricultural land was absolutely limited; once this limit had been reached, continuing population growth would require increasing intensity of cultivation and, consequently, would bring about diminishing returns per capita. The other, or Ricardian, version viewed diminishing returns as a current phenomenon, reflecting decline in the quality of land as successive parcels were brought within the margin of profitable cultivation.2

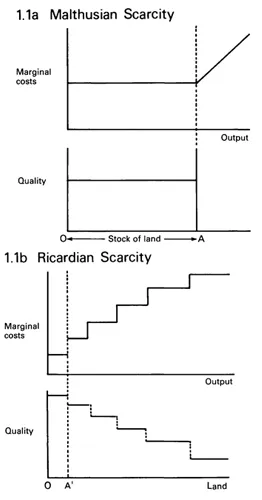

Thus, Malthusian scarcity is assumed to treat natural resources (e.g., agricultural land) as being homogeneous in quality, whereas Ricardian scarcity portrays them as varying in quality. In the absence of technological change, both scarcity effects eventually constrain economic activity; however, they differ in both method and timing. Modern approaches to natural resource scarcity are assumed to be extensions of the Malthusian and Ricardian doctrines.

In terms of method and the timing of diminishing returns, an important distinction is that, for Malthusian scarcity, diminishing returns do not set in until the absolute limits of the available stock of natural resources is reached. In contrast, “Ricardian diminishing returns take effect from the outset, thus requiring no specification concerning the time horizon and no assumption of an absolute limit to the availability of resources”. That is, Malthus “found resource scarcity inherent in the finiteness of the globe”, whereas Ricardo “focused upon the differential fertility of the individual parcel of lands; and assuming that the better lands would be used first, he found declining quality to be the cause of increasing resource scarcity”.3

So in the Ricardian case, increasing production costs set in as soon as resources are used up in order of declining quality; the less fertile the land, the more effort needs to be applied which leads to a rise in the costs per unit of output. In contrast, with Malthusian scarcity, there is assumed to be no difference in the quality of the resource stock; therefore, costs do not rise until the absolute limits of the stock are reached. These contrasting scarcity effects are depicted in Figure 1.1.

As shown in Figure 1.1a, Malthusian scarcity reflects a situation of absolute scarcity. The finiteness of resources – the physically limited stock of land – acts as a constraint on the expansion of output. Moreover, it is only when this absolute limit is reached that this scarcity effect is conveyed by rising costs (prices). Once this has occurred, however, the entire stock of natural resources is fully employed, and the increase in costs is ineffective in encouraging substitution among resources. Economic activity is abruptly halted without any chance of adjustment.

However, Ricardian scarcity exhibits all the characteristics of relative scarcity (see Figure 1.1b). As resources are used in successive grades of declining quality, the costs of resource-use rise. Consequently, as soon as the initial stock of the highest quality resource is fully employed (O A1), physical scarcity is translated into relative scarcity measured by price movements. The economic system should therefore automatically

Figure 1.1: Malthusian and Ricardian Scarcity

respond to such price signals by substituting for the more expensive, relatively scarce natural resource.

A situation of Ricardian scarcity does not necessarily imply the existence of an absolute limit to resource availability: “There is always another extensive margin, another plateau of lower quality, which will be reached before the increasing intensity of utilization becomes intolerable”.4 As long as there are sufficient factors working to offset the progression of Ricardian diminishing returns, either by making poorer quality resources more economical to exploit or by allowing the substitution of previously unexploited resources and synthetic alternatives, then there should be no long-term constraint on economic activity. The rising relative costs accompanying any Ricardian scarcity effect should stimulate technical progress and thus foster “discovery or development of alternative sources, not only equal in economic quality but often superior to those replaced”.5 This existence of Ricardian scarcity implies that economic growth may lead to a temporary, increasing relative scarcity of a particular stock of resources, but this does not necessarily lead to an absolute constraint on growth.

SMITH, MALTHUS AND RICARDO

The use of the Malthusian and Ricardian distinction by Barnett and Morse and others suggests that the contemporary debate has its fundamental roots in, and perhaps was even anticipated by, classical economic approaches to scarcity. A brief review of the classical treatment of the problem by Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus and David Ricardo should reveal the extent to which classical approaches anticipated the conflicting contemporary approaches with respect to:

i) the role of price as a measure of “relative” (exchange) scarcity;

ii) the role of natural-resource inadequacy as an “absolute” constraint on growth; and

iii) the role of technological progress in alleviating any scarcityinduced constraints on growth.

Classical economics differs substantially from modern neo-classical economics. For one thing, the primary concern of the classical economists was not to demonstrate the allocative efficiency of the market system but to explore the social, economic and natural conditions determining economic growth: “… considerations concerning ‘allocative efficiency’ were eclipsed by broader considerations concerning the means of raising the physical productivity of labor and expanding the total volume of economic activity”.6 Moreover, classical economic views on scarcity were often more consistent with those developed by the “natural law” philosophers (such as Francis Hutcheson, Gershom Charmichael and Samuel von Puffendorf) and the Physiocrats (such as Quesnet), whose writings formed the ideological basis for the classical doctrines. Although in the natural law theories there was some appreciation that the relative scarcity of goods has a determining influence on the structure of relative prices, these theories did not endorse the neo-classical notion of relative scarcity as the fundamental economic problem and the rationale for the existence of prices as indices of scarcity.7 These fundamental differences with modern economics limit the extent to which classical scarcity doctrines can be compared with the contemporary economic debate over natural resource scarcity.

Adam Smith

In the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith was searching for an unvarying standard of value that could account for and measure increases in the “real wealth” of nations and, for this purpose, “market values which depended on monetary whims and fashions, on temporary relations between supply and demand, did not appear satisfactory”.8 For this reason, he emphasized the distinction between the true value, or “natural price”, of a commodity and its market price, where the former is determined by “the amount of labor commanded in the market” and the latter by the “relative scarcity” of goods in short supply.9 Thus price may serve in the marketplace as an indicator of the relative scarcity of goods in short supply versus those in abundance but relative scarcity was neither the fundamental resource problem nor an explanation of “how prices came to be what they are”.

Smith did not consider that the finite limits of the earth, or any other natural-resource scarcity problem, would pose a threat of an absolute constraint on economic growth. Instead, “Smith’s account rested on the presupposition that nature was generous … like the Physiocrats before him, he viewed agriculture as capable of yielding outputs far in excess of inputs”.10 Smith placed great emphasis on the accumulation of capital to raise labour productivity in agriculture11. None the less, although he believed that economic stagnation would not arise from diminishing returns in agriculture imposed by absolute resource limits (i.e., on arable land), Smith’s writings do suggest that, despite increased productivity, overwhelming economic dependency on agriculture would eventually increase demand for agricultural output in excess of supply. Prolonged excess agricultural demand would lead to profound distributional impacts, in terms of exchange relationships, private property institutions and the pattern of income distribution. It is these distributional and social responses to the relative scarcity of agricultural output – and not the economic dependency on natural resources – that eventually produce a stationary state.12

Smith’s doctrine does contain some semblance of the modern...