![]()

Chapter 1

Transport and Third World City Development

Harry T. Dimitriou

INTRODUCTION

This book is concerned with the planning of transport in Third World cities within an overall environment of rapid change and development. The principal purpose of this chapter is twofold. First, it is to provide the reader with a Third World contextual framework for the contributions which follow. Second, it is to trace the role of urban transport in Third World cities (especially those of 500, 000 inhabitants and above), in circumstances of changing ideas and expectations about urban development and the function of the transport sector.

DEFINING THE THIRD WORLD

Problems of Definition

Although the ‘Third World’ is now a widely used term, it is employed in so many different ways that one cannot assume a universal definition. As Worsley points out (1980), this is not merely due to a lack of intellectual rigour but is also the result of various historical conceptions of the term that evolved at different times in response to different situations. According to the same source, the term was first used by the French demographer, Alfred Sauvey, who in the title of an article written in 1952, applied it to those countries which were outside the two international power blocs, and also, at the time, outside the communist world. In this paradigm, the ‘First World’ refers to the capitalist industrialised countries; the ‘Second World’ is made up of the centrally planned economies; and the ‘Third World’ represents the remaining ‘developing’ countries’.

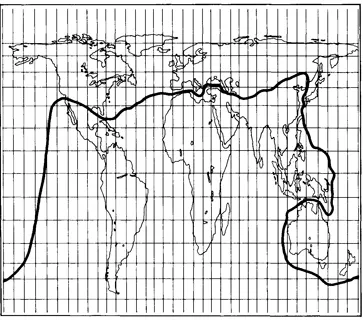

The initial use of ‘Third World’ as a term was therefore, closely associated with the ‘Third Force’ concept, coined by French scholars in the late 1940s and early 1950s, to denote a non-aligned force. In the late 1960s, newly established African countries employed a similar non-aligned intepretation. When East-West tensions declined, and more colonies emerged as new countries, the connotations of ‘Third Force’ with non-alignment altered. The term re-emerged in the 1970s, to connote develop-ment with common characteristics. The notion of confrontation however, was transferred to the North-South dialogue (or rather, lack of dialogue), as summarised by the Brandt Report (Independent Commission on International Development Issues, 1981). This later paradigm presents the ‘North’ as containing all the capitalist countries of the Western world (the majority of which, apart from Australia and New Zealand are located in the Northern hemisphere), as well as the centrally directed economies of the Comecon Countries (excluding Cuba and China); and the ‘South’ as including the majority of the poor nations, also referred to as the ‘Third World’ or the ‘developing nations’ (see Figure 1.1).

If the three world paradigm is too simple, then there are obvious objections to an even more simplified view of the world as two broad camps. This is particularly so since the ‘South’ includes affluent newly industrialising countries (‘the Nics’) such as Korea and Taiwan, at one end of the scale, and poor nations such as Bangladesh and Chad at the other. The division becomes even more misleading if one focuses on per capita GNP figures. Some countries in the ‘South’ (mostly oil-exporting nations such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait) have higher per capita GNP figures than many countries of the industrialised ‘Northern World’ (Table 1.1 — see Appendix 1).

Despite these limitations of definition so well articulated by Harris (1986) in his book ‘The End of the Third World’, the editors of the present book are of the view that as a term ‘Third World’ still has a substantial degree of conceptual validity in its representation of countries with a common past or present set of deve lopment experiences. For this reason this term rather than ‘Developing Country’ is used by the editors. Since to use the latter would erroneously imply that only so-called ‘Developing Countries’ are

Figure 1.1: The North-South Divide

Source: Redrawn from book cover, Independent Commission on International Development Issues, 1981.

making ‘progress’, and that there is a universally known and accepted form of ‘development’ to progress to.

The latter presumption is seen by Bauer (1971) to encourage the imposition as international standards of the development indices of the industrialised world. Countries that do not meet or share these standards are then by implication considered ‘backward’. Bauer goes on to argue that the use of either of the terms — ‘underdeveloped’ or ‘developing’ countries — suggests that their conditions are not only abnormal but rectifiable. Whereas, in fact, the real chances of improving the situation of many Third World countries are small, since the industrialised capitalist and Eastern European countries enjoy more than four-fifths of the world’s income. On this basis, Bauer concludes that in reality, it is the ‘Northern Nations’ that are ‘abnormal’ in as much as they are exceptional.

Third World Characteristics

The case for referring to a bloc of countries as the ‘Third World’, despite all the dangers of over-simplification, arises from their shared socio-economic features (some past and some present), and the international sense of solidarity their common experiences have generated. Third World country characteristics can be summarised and discussed under the following headings:

1. dependence on the industrialised world, combined with a shared perception of their historical development experiences;

2. rapid growth phenomena in major socio-economic trends affecting development;

3. a dual economy with widespread inequalities; and

4. a dominant role played by the public sector in national development.

Dependency. The sense of solidarity among Third World nations is reinforced by the common colonial past of many of them, during which the colonised countries became the main providers of raw materials to the then industrialising nations. It is argued by some (see later discussion on structural-internationalists) that this dependency is currently being perpetuated through:

1. international trade, foreign investment and the activities of multi-national enterprises;

2. international monetary arrangements, foreign aid and related activities;

3. international consulting organisations;

4. Western university education, training and literature; and

5. the research and development activities associated with all the above.

These activities and interests, pursued in close collaboration with a small indigenous elite, are also claimed to reinforce further the dominant position of the industrialised countries over the Third World.

Shared Perception of Historical Development Experiences. An increased sense of common purpose in the Third World has, according to Mabogunje (1980), arisen out of the realisation (substantiated by development planning failures) that the aid and loan policies of capitalist countries with their associated development strategies are not necessarily the effective ‘medicine’ they were thought to be. In certain instances, this realisation has led to a search for new and more appropriate development strategies. Some of these strategies relating to the urban transport sector are discussed in this book.

Rapid Growth Phenomena. None of the numerous indicators representing the common plight of Third World countries is perhaps more striking than their high population growth rates (Table 1.2 — see Appendix 1). Associated population characteristics include (World Bank, 1985):

1. a high participation of the total labour force in agriculture, generally between 30 per cent (for middle income economies) and 59 per cent (for low income economies), compared with an average of 6 per cent in the industrialised countries);

2. a significant proportion of the total population residing in rural areas, averaging between 36 per cent (for middle income economies) and 78 per cent (for low income economies), compared with an average of 23 per cent in the industrialised countries); and

3. relatively low per capita GNP, ranging from an average of US$1, 300 (for middle income economies) to US$260 (for low income countries), compared with an average US$11, 060 for the industrialised nations.

A feature of Third World rural populations is that their social and cultural values are in direct contrast to (if not in conflict with) urban values. The life-styles of Third World city-dwellers, on the other hand, are greatly influenced by industrialisation and modernisation, both of which are commonly associated with trends of rapid urbanisation (discussed at greater length later in this chapter).

Rapid urbanisation in many Third World countries has reached critical levels (Table 1.3 — see Appendix 1). In middle and low-income economies, respectively, urbanisation has increased by an average of 3.5 per cent and 3.7 per cent per annum. In the high-income oil exporting nations, it has even risen by an average of 6 per cent per annum, compared with an average of 1.5 per cent per annum in the industrialised countries. The increase in urban population has taken place largely because of the fast growing population movements from rural to urban areas, and an over-concentration of new employment opportunities in the cities. In addition, natural population growth rates are rapid within many such settlements.

Together, these growth phenomena have created a lethal combination of interrelated and self-generating urban problems of enormous proportions. Problems of urban transport associated with the rapid growth in vehicles (see later discussion and Chapter 2), are but one integral component of the wider urban development situation of Third World cities.

The backcloth to these circumstances in most of these countries consists of (World Bank, 1985):

1. widespread under-employment;

2. a lack of skilled manpower especially at managerial levels;

3. occasional high rates of inflation (a 29.3 per cent per annum average for middle-income economies, compared with 8 p...