![]()

Energy availability in athletes

Anne B. Loucks1, Bente Kiens2, & Hattie H. Wright3

1Department of Biological Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, USA, 2The Molecular Physiology Group, Department of Exercise and Sport Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, and 3Center of Excellence for Nutrition, Faculty of Health Sciences, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Abstract

This review updates and complements the review of energy balance and body composition in the Proceedings of the 2003 IOC Consensus Conference on Sports Nutrition. It argues that the concept of energy availability is more useful than the concept of energy balance for managing the diets of athletes. It then summarizes recent reports of the existence, aetiologies, and clinical consequences of low energy availability in athletes. This is followed by a review of recent research on the failure of appetite to increase ad libitum energy intake in compensation for exercise energy expenditure. The review closes by summarizing the implications of this research for managing the diets of athletes.

Introduction

In the 2003 IOC Consensus Conference on Sports Nutrition, evidence was presented that many athletes, most often female athletes, were deficient in energy, and especially energy in the form of carbohydrates, resulting in impaired health and performance (Loucks, 2004). It was emphasized, however, that energy balance is not the objective of athletic training whenever athletes seek to modify their body size and composition to achieve performance objectives. They then need to carefully manage their diet and exercise regimens to avoid compromising their health.

Distinctions between energy availability and energy balance

In the field of bioenergetics, the concept of energy availability recognizes that dietary energy is expended in several fundamental physiological processes, including cellular maintenance, thermoregulation, growth, reproduction, immunity, and locomotion (Wade & Jones, 2004). Energy expended in one of these processes is not available for others. Therefore, bioenergeticists investigate the effects of a particular metabolic demand on physiological systems in terms of energy availability. They define energy availability as dietary energy intake minus the energy expended in the particular metabolic demand of interest. In experiments investigating effects of cold exposure, for example, energy availability would be defined, quantified, and controlled as dietary energy intake minus the energy cost of thermogenesis.

Exercise training increases, and in endurance sports may double or even quadruple, the amount of energy expended in locomotion. In exercise physiology, therefore, energy availability is defined as dietary energy intake minus the energy expended in exercise (EA = EI − EEE). As the amount of dietary energy remaining after exercise training for all other metabolic processes, energy availability is an input to the body’s physiological systems.

In the field of dietetics, the concept of energy balance has been the usual basis of research and practice. Defined as dietary energy intake minus total energy expenditure (EB = EI − TEE), energy balance is the amount of dietary energy added to or lost from the body’s energy stores after the body’s physiological systems have done all their work for the day. Thus energy balance is an output from those systems. For healthy young adults, EB = 0 kcal · day−1 when EA = 45 kcal · kg FFM−1 · day−1 (where FFM = fat-free mass).

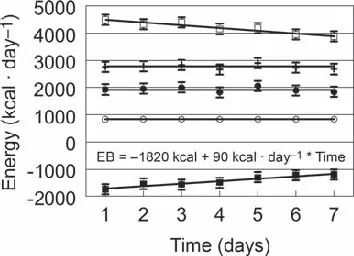

The contrast between energy availability and energy balance is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows data collected while eight lean, untrained men lived in a room calorimeter for a week (Stubbs et al., 2004). During that week, their energy intake (2770 kcal · day−1), exercise energy expenditure (840 kcal · day−1), and energy availability (2770 − 840 = 1930 kcal · day−1 ≈ 30 kcal · kg FFM−1 · day−1) were constant. Meanwhile, the magnitude of their negative energy balance (2770 − 4500 = −1730 kcal · day−1 on Day 1) decreased towards zero at a rate of ~ 90 kcal · day−1 as various physiological processes slowed down. At this rate, they would have recovered EB = 0 kcal · day−1 (a pathological state of energy balance achieved by suppressing physiological systems) in 3 weeks, while remaining in severely low energy availability.

Figure 1. Negative energy balance rising at a rate of ≈90 kcal · day−1 as metabolic processes were suppressed while the energy intake (2770 kcal · day−1), exercise energy expenditure (840 kcal · day−1), and energy availability (2770 − 840 = 1930 kcal · day−1) of eight lean, untrained men remained constant. EI (+) = energy intake, TEE (□) = total energy expenditure, EEE (○) = exercise energy expenditure, EA (●) = energy availability, EB (■) = energy balance. Original figure based on data in Stubbs et al. (2004).

Undergraduate nutrition textbooks assert that energy requirements can be determined by measuring energy expenditure, but measures of energy expenditure contain no information about whether physiological systems are functioning in a healthy manner. Because physiological processes are suppressed by severely low energy availability, measurements of total or resting energy expenditure will underestimate a chronically undernourished athlete’s energy requirements.

Therefore, because energy balance is an output from, rather than an input to, physiological systems, because it does not contain reliable information about energy requirements, and because it is not even the objective of athletic training, energy balance is not a useful concept for managing an athlete’s diet.

Energy deficiency in athletes: Existence, aetiologies, and consequences

At the 2003 IOC Consensus Conference, the existence of widespread energy deficiency in athletes was still questioned. Since then, the IOC Medical Commission has published two position stands (Sangenis et al., 2005, 2006) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) has published a revised position stand (Nattiv, Loucks, Manore, Sundgot-Borgen, & Warren, 2007) on the “female athlete triad”. In addition, a coaches’ handbook on Managing the Female Athlete Triad developed by the co-chairs of the athlete interest group of the Academy of Eating Disorders has been published by the US National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) (Sherman & Thompson, 2005). All four publications attribute the functional hypothalamic menstrual disorders and low bone mineral density found in many female athletes to energy deficiency, but the ACSM position stand differs from the other three in that it excludes disordered eating and eating disorders as necessary components of the triad. The ACSM emphasizes that athletes who expend large amounts of energy in prolonged exercise training can become energy deficient without eating disorders, disordered eating or even dietary restriction.

The ACSM identified three distinct origins of energy deficiency in athletes. The first is obsessive eating disorders with their attendant clinical mental illnesses. The second is intentional and rational but mismanaged efforts to reduce body size and fatness to qualify for and succeed in athletic competitions. This mismanagement may or may not include disordered eating behaviours such as fasting, diet pills, laxatives, diuretics, enemas, and vomiting that are entrenched parts of the culture and lore of some sports. The third is the inadvertent failure to increase energy intake to compensate for the energy expended in exercise. The percentages of cases of the female athlete triad originating from these three sources are unknown, but ACSM emphasized that any epidemiological study requiring the presence of an eating disorder or disordered eating for diagnosing cases of the triad (e.g. Schtscherbyna, Soares, de Oliveira, & Ribeiro, 2009) will underestimate its prevalence.

Sports vary greatly in the relative importance of various factors for competitive success. As they strive to achieve sport-specific mixes of these factors, athletes engage in different diet and exercise behaviours that impact energy availability. In endurance sports, prolonged exercise training greatly reduces energy availability, unless energy intake is increased to replace the energy expended in exercise. In sports where less energy is expended in training, dietary restriction may be a prominent part of the strategy for reducing energy availability to modify body size and composition.

Female athletes may also under-eat for reasons unrelated to sport. Around the world about twice as many young women as men at every decile of body mass index perceive themselves to be overweight (Wardle, Haase, & Steptoe, 2006). The disproportionate numbers actively trying to lose weight are even higher, and this disproportion increases as body mass index declines, so that almost nine times as many lean women as lean men are actively trying to lose weight! Indeed, more young female athletes report improvement of appearance than improvement of performance as a reason for dieting (Martinsen, Bratland-Sanda, Eriksson, & Sundgot-Borgen, 2010). Thus issues unrelated to sport may need to be addressed to persuade female athletes to eat appropriately.

The controversy about whether female athletes can increase glycogen stores as much as male athletes is instructive in this regard. An experiment in which participants consumed diets containing high and low percentages of carbohydrates found that women could not do so (Tarnopolsky, Atkinson, Phillips, & MacDougall, 1995). Subsequently, it was noted that the total energy intake (per kilogram of body weight) of the women in that study had been so low that the amount of carbohydrate they consumed on the high percent carbohydrate diet was no greater than the amount consumed by the men on the low percent carbohydrate diet. Later research showed that women could, indeed, load glycogen like men when they ate as much as men (per kilogram of body weight) (James et al., 2001; Tarnopolsky et al., 2001).

In the 2003 IOC Consensus Conference, the disruption of reproductive function at energy availabilities < 30 kcal · kg FFM−1 · day−1 was discussed in some detail and the low bone mineral density (BMD) found in amenorrhoeic athletes was represented as being mediated by oestrogen deficiency (Loucks, 2004). Since then, oestrogen-independent mechanisms by which low energy availability can reduce BMD have also been identified (Ihle & Loucks, 2004). As energy availability declines, the rate of bone protein synthesis declines along with insulin, which enhances amino acid uptake, in a linear dose–response manner. By contrast, the rate of bone mineralization declines abruptly as energy availability declines below 30 kcal · kg FFM−1 · day−1, as do concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-1 and tri-iodothyronine. These effects occurred within 5 days of the onset of energy deficiency, and without a reduction in oestrogen concentration.

In older adults, fracture risk doubles for each reduction of one standard deviation below mean peak young adult BMD. In adolescents, fracture risk can rise even as BMD increases. Because BMD normally doubles during the decade of adolescence, a child entering adolescence with a high BMD relative to others of the same age can accrue bone mineral so slowly that adulthood is entered with a relatively low BMD. Because low BMD is an aetiological factor in stress fractures, anything that impairs bone mineral accrual during adolescence is undesirable. Unfortunately, this is exactly what was found in a study of 183 interscholastic competitive female athletes, of whom 93 were endurance runners and 90 were non-runners (Barrack, Rauh, & Nichols, 2010). The BMD z-scores were similar in runners and non-runners aged 13–15 years, but were significantly lower in runners than non-runners at 16–18 years of age.

Also questioned at the 2003 IOC Consensus Conference was whether energy deficiency and its clinical consequences were a problem among elite athletes. Since then a study of 50 British national or higher standard middle- and long-distance runners found BMD to be lower in amenorrhoeic runners and higher in eumenorrhoeic runners compared with European reference data (Gibson, Mitchell, Harries, & Reeve, 2004). The duration of eumenorrhoea was positively associated with spine BMD, and the rate of bone mineralization was reduced in the amenorrhoeic runners. Alone, the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) is not clinically diagnostic for eating disorders, but in this study scores on the EAT classified one of 24 amenorrhoeic runners and none of nine oligomenorrhoeic runners as having an eating disorder, while eight amenorrhoeic runners and three oligomenorrhoeic runners were classified as practising disordered eating behaviours. This left 63% of the cases of amenorrhoea and 67% of the cases of oligomenorrhoea unaccounted for by the EAT test (Figure 2). Similarly, a low body mass index (<18.5 kg · m−2) failed to account for 67% of the cases of amenorrhoea and 67% of the cases of oligomenorrhoea (Figure 3). Another study diagnosed low BMD (z-score less than –1) in the lumbar spine of 34% and osteoporosis (z-score less than –2) in the radius of 33% of 44 elite British female endurance runners (Pollock et al., 2010). Reductions in BMD over time were associated with training volume. These findings led the authors to recommend that all female endurance athletes un...