- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

In The High Yemen

About this book

First Published in 2002. Scott gives a fascinating account of an expedition that took place in 1937 to the Yemen when the country was closed to Europeans by order of the Imam. Ostensibly a scientific expedition, it possesses great political, cultural, and anthropological interest. The tense negotiations which preceded the expedition and the ultimate success assured that this work remains perhaps the most important account ever written of that forbidding land that occupies the southern half of the Arabian shore.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access In The High Yemen by Hugh Scott,Scott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

INTRODUCTORY

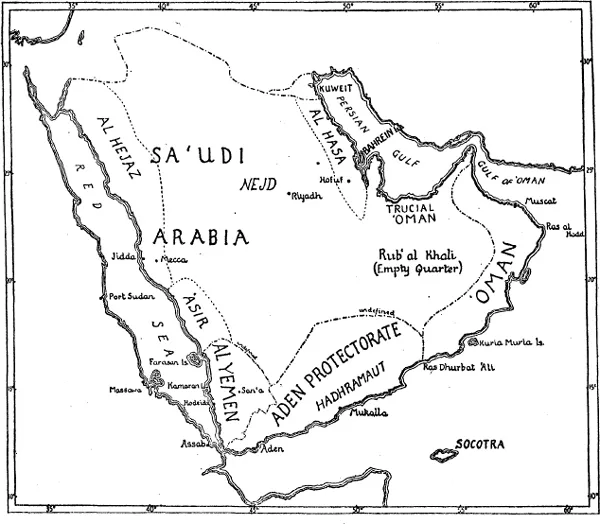

MAP 1. The major political divisions of the Arabian Peninsula: international frontiers (approximate) indicated by alternate heavy lines and dots. Within the Kingdom of Sa‘udi Arabia the former provinces of Al Hejaz, ‘Asir and Al Hasa are indicated by broken lines. Besides the Sa‘udi Kingdom, the principal states and territories are the Sultanate of Kuweit; the Sheikhdom of Bahrein; the Sultanate of ‘Oman (Trucial ‘Oman excluded); the Colony of Aden and the Aden Protectorate (including Socotra I.); and the Imamate and Kingdom of the Yemen. The block of highlands which were the object of the Expedition extend from ‘Asir in Sa‘udi Arabia through the whole length of the Yemen into the south-western part of the Aden Protectorate.

CORRIGENDA

P. 84, line 23: for “Mufadhal” read “Mufadhdhal” (as the letter dh is doubled).

Pp. 123, 171, 181, 226, 227: the title of the present Imam and of several of his predecessors “Al Mutawakil Allah” should strictly read “Al Mutawakkil ‘al’ Allah”, since the participle mutawakkil (waiting, relying) must in this phrase be followed by the preposition ‘aiā (on, upon).

P. 187, line 2 from bottom: “ajeeb!” should be transliterated ‘ajīb! (“remarkable!”).

P. 222, bottom line: “Khulifah” should read “Khulafa” (plural of Khalīfa).

P. 226, line 14 from bottom of text: “12th century” should read “late 11th century” (‘Abbās, father of Zurei‘, attained (jointly with his brother) the lordship of Aden about 1083, and the descendants of Zurei‘ ruled the principality till the Eyyubite conquest in 1173).

Chapter I

OUTLINE OF THE JOURNEY: DIFFICULTY OF ENTERING THE YEMEN

A LONG the southern half of the Arabian shore of the Red Sea rises a great mountain mass. Its tablelands average 8,000 feet in height, while the higher peaks, as yet incompletely surveyed, tower to more than 12,000 feet above the sea. These highlands stand in the track of the saturated winds of the south-west monsoon, which during the summer months blow from the Indian Ocean towards the heated land masses of Asia. Consequently a heavy and regular summer rainfall renders this the most fertile of all that part of Arabia named, centuries ago, Arabia Felix. In sharp contrast are the deserts and steppes of the interior and the barren coastal strip known as the Tihama.

A great block of these mountains lies in the Yemen, a land on the high-road to the East, yet a closed and hidden land whose very existence is unsuspected by most travellers passing along the Red Sea. To penetrate these fertile highlands of the Yemen Britton and I set out for Aden in August 1937.

We are both entomologists, and members of the staff of the British Museum (Natural History) at South Kensington. We had been given leave of absence to make an expedition into the mountains of South-West Arabia, principally to form representative collections of the insects of the region. The causes which led us so ardently to wish for this are outlined in the second chapter.

For political reasons the Expedition was no easy matter, and for the last month before leaving England we had been beset by the gravest doubts as to whether we should succeed in our ambitious project. The highlands which we longed to reach have their northern extremity in the south-western corner of the Kingdom of Sa‘udi Arabia, that is, the province of ‘Asir, a land to which it was impossible to gain admission. The mountains and tablelands continue through the whole length of the Kingdom of the Yemen, and extend beyond its southern frontier into the western division of the Aden Protectorate north and north-west of Aden. One of our principal motives was to investigate the insects, plants, and other forms of life at very high altitudes, say above 9,000 feet. Though the northern part of the British Protectorate is certainly high, its mountains nowhere exceed 8,000 feet. It was, therefore, essential that we should—ruling out ‘Asir as impracticable—enter the Kingdom of the Yemen. Herein lay the difficulty, for the Yemen is a state closed to Europeans except with the express permission of its ruler, the Imam, who as King wields absolute authority and is most jealous of European penetration. Could he be convinced of the innocence of our purpose?

The Imam of the Yemen has no permanent representative in Britain, and can only be approached through the Colonial Office and the Government of Aden. Sir Bernard Reilly, Governor of Aden, while on leave in England in 1935, discussed the subject with me sympathetically, but warned me of the difficulty of getting permission to enter the country. He had, in 1934, headed a Mission to San‘a, the capital, and carried through the delicate negotiations for the Treaty of San‘a, by which the British Government officially recognised the Imam as King of the Yemen. Nothing, therefore, must be done to imperil the existing friendly relations with the Imam. The proposal that I should be allowed to enter the country could only be broached at a propitious moment. This did not occur till the end of 1936, when the Imam consented, under certain restrictions, to our visit.

In July 1937, however, the Imam withdrew the permission given six months earlier through his Foreign Secretary, saying he would prefer the Expedition to be “postponed”. But in the meantime our preparations were complete, and we decided to travel to Aden and work in the mountainous parts of the British Protectorate until consent to our entry into the Yemen could be obtained.

On arrival at Aden, acting on the advice of our friend, Captain B. W. Seager, the Frontier Officer, we travelled nearly ninety miles northwards to Dhala, capital of the Amiri highlands. In this territory, under the friendly protection of the Amir of Dhala, and with the guidance of the British Political Officer, we worked for two months. We camped for over a month at 7,000 feet on Jebel Jihaf, a mountain massif to the north, which reaches 7,800 feet, and also explored parts of the Wadi Tiban and ascended Jebel Harir, a 7,700-foot mountain at the eastern limit of the Amir’s principality. This first journey into the interior proved of the greatest interest. The Dhala highlands, though politically separated, are geographically a continuation of the Southern Yemen. The collections made there, though on the whole from slightly lower altitudes, are equal in value with what we subsequently found in the Yemen itself.

At the end of November, soon after our return to Aden, the Aden Government at length got permission from the Imam for us to visit Ta‘izz, in the Southern Yemen. Setting out from Aden early in December, we reached that city, where, after a stay of three weeks, our permit was extended to the capital. We then travelled to San‘a through the central highlands, by way of Ibb, Yarim and Dhamar. After a sojourn of more than two months, and smaller journeys round the capital, we travelled down to Hodeida, on the Red Sea coast.

So at length, after long periods of waiting and hope deferred, we covered in this second journey a large part of the highlands of the Yemen, the country “on the right hand” or, as some would derive it, the land of happiness and prosperity.1

1 Regarding the meaning of the name, see p. 204.

Chapter II

OUR SCIENTIFIC QUEST

THAT we should have persisted in carrying out our expedition despite delays and disappointments presupposes an ardent desire to visit the country. I shall, therefore, try to explain why an expedition to the fertile highlands of South-West Arabia was to me a long-cherished project. It is necessary to outline, as simply as possible, how the countries bordering on the southern end of the Red Sea came to have their present geological structure; also how this affects their climate to-day, and the climatic changes which have taken place before and since early historic times. In the third chapter is told what kind of collections we made and our ways of collecting specimens, while the fourth is devoted to a short review of earlier exploration of the Yemen by naturalists.

The south-western corner of the Arabian peninsula is of peculiar interest, because its fauna and flora link on to and overlap those of three great biogeographical regions—the Northern or Palæarctic, the Oriental, and the Ethiopian or Tropical African. The interest which I and my colleague felt in the geographical distribution of its animals and plants had arisen independently. To both of us South-Western Arabia presented large areas almost entirely unexplored from our standpoint. While, however, Britton was keenly interested in the possibility of finding links with the countries to the north and east, the motive which led me to work so ardently for an Arabian expedition was mainly a desire to compare the fauna and flora of the South-West Arabian highlands with those of the Abyssinian highlands on the opposite side of the Red Sea, which I had visited eleven years before.

There exist, as said, two great blocks of highlands, one on either side of the southern end of the Red Sea. Their core consists of ancient crystalline rocks on which have been superimposed, in very remote epochs during which the area was submerged below the sea, huge thicknesses of several successive formations, corresponding mainly to the Jurassic and Cretaceous of Europe. The latter period, when our chalk was formed, is represented in Ethiopia and South-West Arabia chiefly by sandstones about 1,100 feet thick. After their deposition the whole area was, at the end of the Cretaceous or in early Tertiary time, uplifted far above sea-level, and a phase of faulting, the formation of cracks in the earth’s crust, set in. This was accompanied by a mighty outpouring of molten volcanic rock which solidified into enormously thick layers of “trap” (in central Yemen they have been estimated at over 2,000 feet thick); the trap to this day constitutes great areas of the high tablelands, and has been subsequently eroded, so that in places it ends in sheer cliffs or stands in gigantic detached slabs (Phot. 89). The cracking of the earth’s crust mentioned above, continuing in successive phases over a vast period of time, resulted in the sinking in of three great trough-faults or rifts, namely the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden, and the northern extremity of the complicated system of East African rifts. These three great trough-faults, meeting at the narrow Straits of Bab el Mandeb, have cut across the formerly continuous uplifted block and separated the Abyssinian from the Yemen highlands.

The process of cracking, the pushing up to thousands of feet above sea-level of some blocks of the earth’s crust and the sinking in of others, occurred in successive phases. Three great systems of faults are distinguishable, one running north-north-west and south-south-east, or parallel to the length of the Red Sea, a second running due north and south, and a third almost at right angles to the first, parallel to the Gulf of Aden. The succeeding phases gave rise to step-like formations, so that we now have the Red Sea lying in its deep trough, a narrow belt of lowlands along the coast on either side, and the great mountain ramparts rising in steps to the high plateaux. The high plateaux of the Yemen are, however, not merely the bent-up and broken-off edge of the land-mass constituting the peninsula, but are a block which has been uplifted along lines of faulting on both sides, so that it falls away (though less precipitously) on the east towards the deserts of the interior, as well as on the west towards the Red Sea. The isolated high tablelands thus formed lie at 7,000 to 9,000 feet above sea-level. From them peaks and ranges soar to far greater altitudes.

In the later part of the period of faulting, comparatively recent volcanic outbursts occurred. These eruptions, separated by a very long interval from the earlier outpourings of trap, probably began in the first part of the Tertiary period and have continued in successive phases down to historic times. Some of the works of man were probably overwhelmed by the later outpourings, and the whole area is one in which dying volcanic activity is still manifested by the presence of vapour-emitting fissures and numerous hot mineral springs. To this recent volcanic period belong many extinct cones and craters in Abyssinia and South-West Arabia. On the Arabian coast it comprises the Aden peninsula itself and other craters west of it, and many of the grim, barren islands in the Red Sea, such as Perim, the Hanish Islands, the Zubair group and Jebel Tair. In the interior it has given rise to the areas known as “Harra”, such as the Harra of Arhab, north of San‘a, a desolate-looking tract of red cones and grey-black, scarcely weathered, lava-flows (Phots. 97, 98), reflected in the use of black lava-blocks for building houses and walls round fields.

Finally, the most recent formations are alluvial and æolian deposits, according as they have been accumulated by the action of water or wind. Such are, first, the narrow strips of coastal lowlands or desert country known as Tihama, and, second, the thick beds of wind-accumulated dust (a coarse-grained kind of “loess”) forming the plain surrounding San‘a, not far short of 8,000 feet above sea-level. On these latter deposits the largest city in Southern Arabia depends for its very existence. Rain-water, sponged up by this extremely porous substance, is tapped by numerous deep wells, and the bricks of the city’s ancient encircling walls and of the greater part of its houses, old and new, are made of the same material.

What sort of climate the country may have enjoyed during the earlier phases, after its uplift and separation from Africa by the Red Sea rift, is too complex a question to discuss here. But there is evidence that great changes have occurred in more recent geological times, within the Pleistocene period. Within this limit (perhaps a million years) South-West Arabia has been subjected to alternating wetter and drier episodes. The cooler and wetter phases (“pluvials”) were probably contemporaneous with those of which evidence has been discovered in East Africa, and which are believed to have synchronised with periods of glaciation farther north. In Pleistocene times there appear to have been two major pluvial episodes, separated by a drier phase during which occurred the earlier outbursts of recent volcanic activity. Much later there has apparently been a new wet phase, continued into the early centuries of the Christian era.1 Since its cessation, the gradual process of drying has extended outwards towards the coast, a change referred to again in the historical summary, Chapters XIX and XXII.

The natural processes outlined above, extending over long epochs of time, affect present conditions as follows. The high plateaux and lofty mountains catch the summer monsoon and have abundant rains from June to September. Streams, waterfalls and rivers, many of which flow perennially, exist at medium and high altitudes in the interior. Those flowing outwards do not normally reach the sea, but are lost in the sands of the Tihama. They shrink greatly in the winter months, when the boulder-strewn water-courses of the wadis are usually almost dry. In summer, however, the rivers are liable to rise suddenly and rush down as torrents. Deep and steep-sided valleys, canyons and gorges have thus been scored in the ranges and the edges of the tablelands. Other streams flow inwards, descending more gradually from the watershed formed by the high mountains fringing the outer edge of the highlands. The waters of this latter series may peter out in the arid interior; but the wadis in which they flow may join great vall...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contents

- Note of Acknowledgment

- Note on Transliteration and Dates

- List of Photographs

- Note on Photographs

- List of Maps and Figures

- Part I. Introductory

- Part II. The Journey

- Part III. Historical—and the Future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index