![]()

I

Theory Building and Theory Appraisal

Our survey of Paul Meehl’s psychological writings begins with five chapters focusing on the twin themes of theory building and theory appraisal. Meehl addressed these themes often in his writings and thus these chapters offer an ideal vantage point from which to study his psychological work (for a survey of his philosophical writings see Meehl, 1991).

We begin with one of Meehl’s most influential papers: “Construct validity in psychological tests.” Co-written more than a half century ago with Lee J. Cronbach, construct validity is a citation classic that is among the 10 most highly cited works published in Psychological Bulletin (Sternberg, 1992). To fully appreciate the article’s role in shaping contemporary views on test theory it is helpful to view the work from a historical perspective.

During the early 1950s, Cronbach and Meehl served on an American Psychological Association (APA) task force (along with Robert Challman, Herbert S. Conrad, Edward Bordin, Lloyd Humphreys, and Donald E. Super) charged with drafting the first professionally endorsed standards for psychological testing. Although Cronbach and Meehl were satisfied with the committee’s final product as an official report (APA, 1954), the two authors agreed to write a more elaborate description of the report’s most novel and controversial idea, the notion of construct validity. According to Cronbach,

Meehl originated the idea of construct validation as a way to think about testing that is intended more to describe a person than to assess proficiency on a defined task or to predict a prespecified performance. The committee asked me, as its chairperson, to help present the view it had endorsed in outline. In the writing, Meehl contributed the philosophical base and much experience in personality measurement, I brought in experience with tests of other kinds, and we worked out the advice on research methods jointly. At Meehl’s insistence, authorship was determined by coin toss. (Cronbach, 1992, p. 391)

Much of the controversy engendered by the article was due to the authors’ explicit rejection of operationism. According to Cronbach and Meehl “[c]onstruct validation is involved whenever a test is to be interpreted as a measure of some attribute or quality which is not ‘operationally defined’” (p. 10). In today’s intellectual milieu—a climate that was importantly shaped by Cronbach and Meehl’s paper—few psychologists would argue with this claim. Nevertheless, when Meehl’s idea was first introduced “many psychologists ... worried that legitimizing construct validity would encourage insubstantial, jawboning defenses of clinical inferences” (Cronbach, 1989, p. 147). This view is understandable considering that, during the period in question, most testing specialists were adherents of psychometric operationism. Gulliksen (1950b) for instance, claimed that “[t]he validity of a test is the correlation of the test with some criterion” (p. 88). Expressing a similar opinion that she would later reject, Anastasi (1950) suggested that “[t]o claim that a test measures anything over and above its criterion is pure speculation of the type that is not amenable to verification and hence falls outside the realm of experimental science” (p. 67).

To claim that Meehl’s brainchild has been warmly embraced by the psychometric community would be an understatement. Evidence for the widespread acceptance of construct validity as an organizing principle for both test validation and trait validation can be found in virtually any contemporary article that deals with psychological traits (e.g., extraversion, general intelligence). In sharp contrast to views expressed a half century ago, many contemporary authors on test theory describe construct validity as the ideational glue that holds together the various other forms of validity (e.g., Angoff, 1988). For instance, Guion (1977) has claimed that “all validity is at its base some form of construct validity” (p. 410).

To learn more about construct validity and how this notion has evolved since Cronbach and Meehl’s original article, see Loevinger (1957); Angoff (1988), and Geisinger (1992). To learn more about the “nomological net,” an important concept that was introduced to psychologists in this work, see Hempel (1952) and Bechtel (1988). Further information on the influence of operationism in psychology can be found in Bridgman (1927, 1945), Israel and Goldstein (1944), Stevens (1935), and Rogers (1989).

The next two chapters in this section address a problem that has plagued methodologists for more than a century: When is it legitimate to make causal inferences from associational data (or more precisely, from data obtained in nonexperimental settings)? The two chapters address this question from slightly different angles and should be read as a pair. “High school yearbooks” was originally written for psychologists and is considerably less challenging than “Nuisance variables and the ex post facto design,” which was originally written for philosophers.

Meehl wrote “High school yearbooks” as a reaction to an earlier publication by Schwarz (1970). The Schwarz article was a comment on an article by Barthell and Holmes (1968). Thus, viewed narrowly, Meehl’s work is a comment on a comment (Schwarz, 1971, responded to Meehl and completed the exchange). Viewed more broadly, however, Meehl’s work stands on its own as an original contribution to the causal inference literature. Meehl suggests that the problem with nuisance variables is that we cannot always ascertain the direction of the causal arrow and thus “the so-called ex post facto ‘experiment’ is fundamentally defective for many, perhaps most, of the theoretically significant purposes to which it has been put” (p. 37). To better understand this claim let us review some key definitions.

The phrase ex post facto, commonly translated as “after the fact,” is Latin for “from a thing done afterward.” In methodological discourse, this term describes a design in which naturally occurring groups are followed through time—either prospectively or retrospectively—in an attempt to determine the causative factors of a psychological trait, behavior, or outcome. A nuisance variable denotes a potentially biasing background variable (i.e., beyond the grouping variable of interest) on which groups initially differ, whether in fact the variable is truly biasing. In “High school yearbooks” Meehl describes how such background variables can easily toss flies into the ointment of an ex post facto design. To motivate his discussion, Meehl considered the Barthell and Holmes (1968) study and its subsequent critique by Schwarz (1970).

Very briefly, Barthell and Holmes consulted high school yearbooks to determine whether reduced participation in high school activities was associated with a subsequent diagnosis of schizophrenia. Schwarz (1970) criticized their study by noting that the authors failed to match the schizophrenic and control groups on putatively important background variables, such as social class. Meehl used Schwarz’s critique as a springboard for considering the broader issue of when adjustment for nuisance variables (e.g., by matching or partial correlations) improves the accuracy of causal inferences.

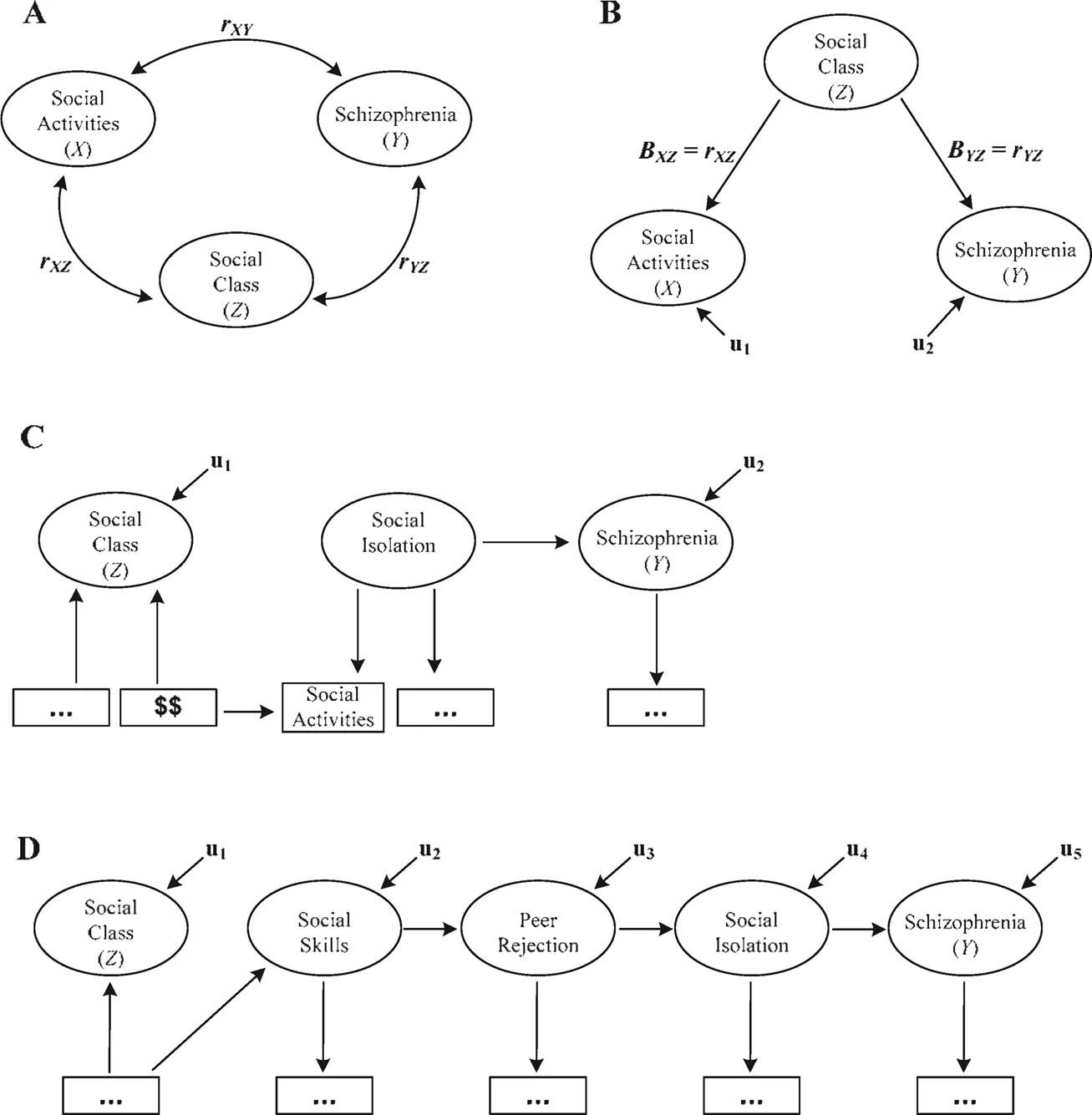

Let us consider Meehl’s arguments with the help of several path analysis diagrams. Figure 1.1 displays four plots which, in aggregate, illustrate Schwarz’s concern and Meehl’s trenchant criticism of the assumptions underlying that concern. In each path diagram ovals represent latent variables, rectangles represent observed variables, directed arrows indicate (standardized) causal relations, and double headed arrows denote correlations (that are silent with respect to causation). A rectangle containing an ellipsis denotes one or more nonspecified measurements or causal indicators.

Consider the following scenario: Researcher Fisbee suspects that during the high school years, social activities (X) protects against later developing schizophrenia (Y). Having noted that social class (Z) is correlated with social activities and schizophrenia—the situation depicted in Diagram A of Figure 1.1—Fisbee wishes to remove this confound by computing the partial correlation of X and Y with Z “held constant.” Diagram B illustrates this adjustment. Notice that if the correlation between social activities (X) and schizophrenia (Y) is completely caused by the common influence of social class (Z), then standard rules of path analysis indicate that rXY will equal rXZ rYZ. This notion can be tested with the partial correlation, which will equal 0.00 if the model depicted in Diagram B is correct.

As noted by Meehl, model (B) is one member of a class of models, no member of which is known with certainty to be true. To illustrate this point, Meehl lists six additional models that can plausibly account for the observed data. Two of these (Meehl’s Cases 1 and 3) are depicted in Figure 1.1. Diagrams C and D denote models in which social class has neither a direct nor an indirect causal effect on social activities. In Diagram C, money ($$) is a component—rather than an indicator—of social class. Consequently, although money influences social activities, social class does not. Similarly, in Diagram D, social class has no influence on social skills. Rather, unspecified components of social class (that being a composite variable) exert an influence on social skills. As Meehl notes, it would be inappropriate to statistically control for social class, through covariate adjustment or matching, in these latter models. In other words, under some scenarios covariate adjustment can actually introduce bias into an ex post facto design rather than remove it. Epidemiologists call this “controlling for a non-confounder.” This important point is treated at greater length in “Nuisance variables and the ex post facto design,” a work in which Meehl also treats the deeper philosophical issues involved in causal analyses.

FIG. 1.1. Different models to explain observed data.

Several chapters in this section offer incisive critiques of Fisherian significance testing in psychology and the life sciences. The use of significance tests to evaluate scientific theories—as opposed to testing merely technological hypotheses (e.g., what fertilizer works best for growing roses)—is a widespread but controversial application of Fisher’s brilliant mathematics (Harlow, Mulaik, & Steiger, 1997). Meehl was an active participant in this controversy for many years, beginning with his highly influential comparison of how significance tests are used in psychology versus in physics (Meehl, 1967a). Chapters 4 and 5 build on this earlier work and offer a number of constructive alternatives (e.g., consistency tests, a corroboration index that takes account of the possible values of a theoretically predicted parameter, or Spielraum) for rigorously testing theoretical conjectures.

The “Two Knights” chapter (after Sir Karl Popper and Sir Ronald Fisher) is yet another citation classic that has helped shape current thinking on theory testing in psychology. It was recently reprinted in Applied and Preventive Psychology (Smith, 2004) along with 17 commentaries. This work continues to attract attention among scholars because of Meehl’s brilliant insights into one of the thorniest questions of our discipline: Why is human psychology so hard to scientize? One reason, according to the article, is our slavish use of null hypothesis refutation to test scientific theories. Stated more colorfully by Meehl,

The almost universal reliance on merely refuting the null hypothesis as the standard method for corroborating substantive theories in the soft areas is a terrible mistake, is basically unsound, poor scientific strategy, and one of the worst things that ever happened in the history of psychology. (p. 72)

This theme is developed at greater length in Chapter 5, an unparalleled critique of the significance test controversy. Drawing on his extensive knowledge of history and philosophy of science, chemistry, physics, psychology, and statistics, Meehl deftly explains why null hypothesis refutation—as implemented in the social sciences—fails to provide meaningful risky tests for scientific conjectures. The work was originally published as a target article followed by 12 commentaries. We have included Meehl’s reactions and reflections to those commentaries in this volume.

Several readers of “Appraising and amending theories” have commented on the article’s difficulty. For instance, one reader (Kimble, 1990, p. 156) noted, “Meehl’s writing is intimidating. The argument goes on and on: much of the literature cited is not psychology; there are words that are not in standard dictionaries ... the acronyms and logical symbols are hard to remember—and the ideas are just plain difficult.” This same reader also noted, “[T]he ideas are ... of prime importance. They deserve attention and, more that that, they command changes in psychology’s outlook on its science” (p. 156). We agree with both opinions.

Meehl suggests that we replace the statement “Is the theory literally true?“—a question that is almost certainly false a priori in soft areas [Meehl’s term] of psychology—with the more productive statement, “Does the theory have sufficient verisimilitude [truth-likeness] to warrant our continuing to test it and amend it?” (p. 152). Recognizing that theories are generally rather imperfect representations of the world, Meehl follows Lakatos (1970) in suggesting that it can be reasonable to amend, rather than abandon, a theory in the face of a certain amount of negative evidence. Conditions under which this so-called Lakatosian Defense is warranted is a subject of the article.

To understand this work in its entirety, it is helpful to have read the philosophical works of Lakatos, Popper, Carnap, and Reichenbach. It is also helpful to understand differential equations, the Boyle-Charles gas law, Gompertz curves, Bayesian statistics, and quantum mechanics. Amazingly, Meehl draws on all of these topics as he weaves the threads of his cogent argument into a tightly knit whole. If you can read four or five books a week, as Meehl did all his adult life (see Waller & Lilienfeld, 2005, for a description of Meehl’s reading habits), then these suggestions will not seem onerous. However, if you are an intellectual mortal, like the rest of us, then you may find the following books and articles helpful as an introduction to one or more of these topics.

Bechtel (1988) has written a highly accessible introduction to 20th-century philosophy of science with material on Popper, Carnap, Reichenbach, and Lakatos. Meehl’s own description of how philosophy helped him think clearly about psychology (chap. 17, this volume) is also required reading. Urbach (1974a, 1974b) has written two excellent papers that illustrate how Lakatosian ideas can be applied in psychology. Elementary introductions to the calculus and formal logic are provided by Adams, Hass, and Thompson (1998) and Bennett (2004).

One need not put off reading Meehl until the aforementioned background material is mastered. As noted in the Preface, virtually all of the articles in this collection can be appreciated at multiple levels. Nevertheless, in order to benefit fully from the arguments in Chapter 5 we believe it is necessary to understand at least a modicum of introductory formal logic.

Table 1.1

Four figures of the implicative syllogism

| I | II | III | IV |

| p ⊃ q | p ⊃ q | p ⊃ q | p ⊃ q |

p | ∼p | q | ∼q |

______ | ______ | ______ | ______ |

∴ q | ∴ ∼q | p | ∼p |

| Modus ponens | Denying the antecedent | Affirming the consequent | Modus tollens |

| If theory is true then observation will occur. | If theory is true then observation will occur. | If theory is true then observation will occur. | If theory is true then observation will occur. |

| Theory is true. | Theory is false. | Observation occurs. | Observation does not occur. |

| Therefore observation will occur. (Valid) | Therefore observation will not occur. (Invalid) | Therefore theory is true. (Invalid) | Therefore theory false. (Valid) |

Table 1.1 summarizes several rules for making valid and invalid deductions (i.e., conclusions) from valid premises. The rules are presented in the form of a syllogism, a didactic device invented by Aristotle and later refined by Galen. The most basic syllogism consists of two premises followed by a conclusion. Each column in Table 1.1 represents a particular figure (form) of syllogistic reasoning. Notice that only two figures—modus ponens and modus tollens—are formally valid. The other figures lead to invalid conclusions.

In “Appraising and amending theories,” Meehl draws our attention to the “formally invalid third figure of the implicative syllogism.” In the context of null hypothesis refutation, this syllogism can be stated:

If Theory T is true then H0, the null hypothesis, will be rejected.

H0 is rejected.

Therefore, Theory T is true.

This conclusion represents an invalid deduction from the premises because other theories, not even remotely related to T, might also result in rejection of H0. This tru...