![]() Part I

Part I

The Indian![]()

Chapter I

The Origin of the Indian

"Why do you call us Indians?"—Query put to John Eliot by the Indians, 1646.

IN the beginning, there was the Indian. We find him on the stage when the first conquerors came. Where did he come from?

The Lost Ten Tribes?

For centuries it was popularly supposed that the Indians were the lost Ten Tribes of Israel. The almost Jewish cast of features of many tribes in eastern and middle-western North Amcriea, and the existence among the Indians of many religious and social customs similar to those of ancient Jewry, helped support this contention. Some of the best of our earlier scientific inquiries into Indian life and history, such as Adair's History (1775) and Lord Kingsborough's monumental publications on Aztec society (1848), were directed to prove the contention of the Jewish origin of the Indian.

Even William Penn, in 1682, while making no contention, was struek by certain resemblances between the Delaware Indians, with their rather high-bridged noses and broad check-bones, and the type of Jew then found in the Jewish section of London.1

"I found them of like countenance," he wrote, "and their children of so lively a resemblance that a man would think himself in Duke's Place or Berry Street in London when he seeth them."

The Ten Lost Tribes theory has, however, been doomed by scientific investigation, and we are sure to-day that those Israelites of the Ten Tribes were absorbed thousands of years ago, into the Babylonian population.

A Transplanted Chinaman

The sharp separation, found in our childhood school-books, of "red", "brown", and "yellow" races, is no longer acceptable. The broad identity of these three racial agglomerations—Indian, Malay, and Mongolian—is so apparent to-day that recently I felt it safe to state that the Indian is, in fact, "about the equivalent of a transplanted Chinaman”.

The objections to such phrasing were, I felt, due to the subconscious contrast occurring to American auditors between the noble, aquiline-nosed Sioux Indians of our American plains, and the despised, sallow, low-bridged nosed Chinaman of the laundries of American cities. The fact remains, however, that the American Indian peoples are very closely akin to the Chinese peoples, racially, linguistically, and culturally. They are parts of the Mongolian—or, better, Mongoloid-agglomeration of racial stocks. These Mongoloid peoples are characterized primarily by their straight, heavy, wiry, black hair, and by skin of varying shades of yellowish and reddish brown.

Old World Kin of the Indian

In Asia, this racial type is represented by the tall, light-skinned northern Chinese, and the Manehus, their Tungusian conquerors; by the short, brown, small-nosed Chinaman of the south; by the Indo-Chinese, Siamese, and Burmese; by the Malays proper and the Filipinos and Javanese; by the Thibetans, Mongols, Koreans, Japanese, and aboriginal Siberian tribes.

In Europe, of course, we have the representative Lapps. Originally, also, the Finns, Esthonians, Hungarians, Tartars, and Turks were of the same racial type and still retain their ancient Mongolian languages, but they have so inbred with Caucasian neighbours that only in the slant eyes and broad faces of occasional peasants does the old racial type persist.

The Polynesians—familiar to Americans acquainted with the Hawaiians—are less closely related to the Indian. To-day we well know that the Polynesian language is merely a sort of broken-down Malay and that the peoples on the various Polynesian Islands are of a late mixture of Mongolian types—probably from the Malay regions—with negro types such as are still found unmixed in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

Various Types of Indian

These Old World Mongolian peoples vary, of course. Compare the high nose of a Javanese aristocrat with the orang-utang nose of a Malay commoner, or the fine lines of a Japanese nobleman's face with the gross broad face of a Japanese labourer. Some of the variation is due to very ancient race-mixtures, which we cannot yet trace, making for differences between groups and variation within groups. Some is due to late mixture. Even to-day the bearded, wavy-haired Ainu is being absorbed through intermarriage by the Japanese. The Samurai of old Japan were considerably of Ainu blood. To-day, as yesterday, the Filipinos and Malays are racially assimilating the kinky-haired negritos still left among them.

So also the American Indian type varies from tribe to tribe, and between family groups within the tribe. There is as much difference between the Sioux of the plains of the United States and the Salish of the Oregon coast as between the Thibetans and the Filipinos. Some of this variation probably developed in the Americas, but there is little doubt to-day that different Mongolian types came into America at different times.

So far we have not spoken of the Eskimo. This people, until recent centuries, inhabited Siberia as well as America. The Siberian Eskimo were once one of the most powerful of the Mongolian peoples of northeastern Siberia. But inasmuch as their range, historically, has been largely the Aretic coasts of America, they are an American group of Mongolians. They are Indian just, as much as any other of the American groups are, although popular language sets them as a group apart.1

The Origin of the Indian Languages; Eskimo Related to Turkish

How did these Mongolians enter the Americas? This is a question which only in very recent years has been approaching a solution aided by the study of the relationships of the American languages. The Freneh scientist Sauvagcot, in a very scholarly monograph published in 1924, gave what appears to most students unequivocal proof of the Old World affinities of the Eskimo language.

In Europe and Asia is a group of languages and dialects all closely related, called the Uralian—or Ural-Altaic stock, spoken only by peoples of Mongoloid racial origin—in contrast, for example, with the Indo-European stock of languages spoken chiefly by the Caucasian peoples. This Uralian stock includes the languages of Finland, Turkey, Esthonia, Hungary, Thibet, Mongolia, and of the Manchus and the Siberian Tungus. Sauvageot has shown that Eskimo is a language of this stock—in other words, that Eskimo is related to Hungarian and Finnish in the sense that Greek is related to Latin, or English to Russian.

Curiously enough, the languages of the Japanese, Koreans, and of the tribes of northeastern Siberia (the Paleo-Siberians or Old Siberians) are not members of the Uralian stock. The Eskimo language, however, contains words borrowed from these non-related languages.

Standing on the American side of the Behring Strait, on a clear day, one may sec the coast of Asia. Often the strait is frozen over. As we have already noted, the Eskimo, some few centuries ago, were a powerful group in Siberia as well as in America. There is conclusive evidence that the American Eskimo are an immigrant off-shoot, of the Asiatic Eskimo,2 entering America by the Behring Strait route and across the islands in the Behring Sea; while at the same or some other time, the Alcuts—whose language is apparently related to theirs—possibly passed along the islands of the Aleutian chain which border the Behring Sea on the south and serve as stepping-stones between Europe and Asia.

Navajo Related to Chinese

The immigrant Eskimo-speaking people from Siberia undoubtedly found peoples already inhabiting Aretic America. Some of these they probably killed off; some they undoubtedly

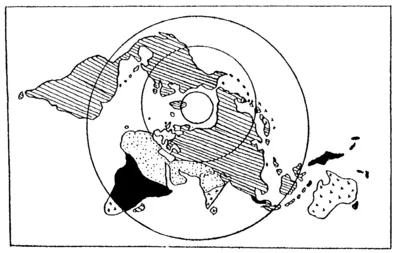

MAP I.—THE RACES OF THE WORLD IN COLUMBUS' TIME.

(For some details sec Appendix X.)

assimilated. These earlier groups had come, perhaps, from Asia also as part of a pre-Eskimo immigration that came by the Behring Sea routes.

It was no doubt by way of the Behring Sea, at some date long before the Eskimo intrusion, that the original Athabasean-speaking group entered Ameriea. The Athabascan languages to-day include those spoken by the Indians in the interior of Alaska, the greater part of the Rocky Mountain plateau of Canada, and by the more familiar Apache and Navajo of the southwest of the United States.

It is the contention of the distinguished American scientist Sapir that Athabascan is closely related to primitive Chinese. He discovered, for example, that the Athabascan Indians used the peculiar system of "tone”, which, to our ears, makes Chinese so much of a sing-song, and by means of which the same words in different tones have widely different meanings.

Australians and Polynesians in America

It is on the authority of the distinguished French scholar Rivet, supported by Dixon and others in Amcrien, that a group of languages including Yuman, spoken notably in upper and lower California, but also in Nicaragua and in Texas and northwestern Mexico—a group known as the Hokan stock—is identified as related closely to the languages of the Malays, Polynesians, and Melanesians—the Melano-Polynesian stock. On the same authority the languages of the Indians of Tierro del Fuego and Patagonia—known as the Tson stock—are related closely to those of the Australian blackfellows.

But how could Australians and Polynesians get into the Americas? These Australians, although nearly as dark as negroes, are not of a negro type. Save for the darkness of skin, with their bushy beards and wavy hair they suggest the Ainu. For a variety of reasons it has long been my opinion that the Ainu are northern and the Australian are southern representatives of a race of Australoid type once dominant over the whole of the Mongolian regions of Eastern Asia at a time when negroid peoples inhabited Malaysia, Polynesia, and Australia.

Recent scientific study would indicate that this Australoid type not only preeeded the Mongolians in Asia but also in the Americas. Very possibly, it, too, came in over the Behring Sea route. This, I think, is more likely than that it came through Polynesia.1

The Polynesian arehipelagos were, however, at some time within the last several thousand years much larger and more populous and rich than when they were first discovered by Europeans. There has been much significant subsidence. Easter Island, the Polynesian island nearest to America, is but a little remnant of what was once undoubtedly a large and populous archipelago inhabited by that rich population which left behind the great monolithic statues still to be seen there.

It is eminently probable that peoples have passed into America from Asia not only by the Behring Sea route but through Polynesia. From Easter Island, perhaps, to the coast of Peru, and then north and south along the coasts, and into the interior. It is possible that it was some group from Polynesia, spreading north, which introduced into Nicaragua, the Gulf Coast of the United States, and California the languages of Malay affinity which Rivet identifies there.1

The Asiatic Origins of Indian Civilization

A very few years ago it would have been only at the cost of his reputation for sanity that an American student might contend that it was in any sense likely that the civilization of the American Indians was to any considerable extent derived from Asia—that, for example, agriculture and mound-building were not evolved independently in America, but were borrowed from Asia. English scholars, such as Rivers, Elliot Smith, and Perry, have been more daring, but their methods of study did not agree with the standards of American students. While being myself at variance with the methodology of the British scholars mentioned, I think, on the basis of my own approach to certain aspects of the problem, that their conclusions are largely acceptable.

Elements of culture, or civilization, entered America as part of the equipment of immigrating peoples. Then through the maintenance of contacts, new inventions were passed from Asia, from one tribe to another in the Americas, by a process of borrowing. Immigrants and culture have, first of all, passed over th...