- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mental Hospitals at Work

About this book

First published in 1998. This is Volume IV, of seven in the Sociology of Mental Health series. Written in 1962, this study looks at of what mental hospitals actually do, what problems they face, how they use their resources, and how their efficiency can be assessed. We begin in Part I by briefly describing the provision of mental hospitals in England and Wales, and analysing current trends in hospital and community care, together with the arguments for and against the retention of the mental hospital.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mental Hospitals at Work by Kathleen Jones,Roy Sidebotham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Sociología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Mental Hospital Today

I

The Impact of Change

AT the time of writing, there are about 130 hospitals in England and Wales which are separately administered, and which receive mental patients exclusively, or almost exclusively. Of these, two have more than 3,000 beds each;1 22 have between 2,000 and 3,000 beds; 48 have between 1,000 and 2,000 beds; 30 have between 500 and 1,000 beds; and the rest have less than 500 beds.

Large mental hospitals occur in two main concentrations: on the fringes of the Greater London area, and in a belt across the Liverpool, Manchester and Leeds conurbations. Small hospitals are generally in less populous areas, such as Somerset, Gloucestershire, or Suffolk.

Most mental hospitals operating today were constructed between 1850 and 1914. There seem to have been two main waves of building, following the Lunatics Act of 1845 and the Lunacy Act of 1890. Only two mental hospitals of more than 1,000 beds have been set up since the First World War.

The Mental Treatment Act of 1930 introduced provision for voluntary patients, and most mental hospital committees made special provision by means of new ‘admission units’ or ‘neurosis units’ for the milder types of cases then admitted.

In addition to these hospitals administered by Regional Hospital Boards, there is one post-graduate teaching hospital group, Bethlem and the Maudsley, and there are four ‘registered hospitals’.

The Bethlem-Maudsley group is a unique combination of the old and the new, Bethlem, the oldest mental hospital in England, originated in a monastic foundation of 1272, and, after a somewhat chequered history, was rebuilt on a new site in 1930. The Maudsley, built immediately before the First World War, was not opened to civilian patients until 1923, when it fulfilled its benefactor’s intention by becoming the first mental hospital to take early, recoverable cases without certificate.2 The two hospitals were administratively united in 1948, and the group is directly responsible to the Ministry of Health.

The four registered hospitals are private, non-profit-making hospitals with a recognized standing. At present, they have about 1,200 beds between them.

In addition, there are increasing numbers of annexes and wings of general hospitals which make provision for psychiatric patients, but are not separately administered, and numbers of small mental nursing homes, which are now inspected by the local authority. These establishments are not included in this survey.

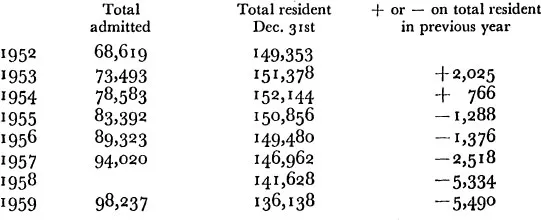

The detailed figures for resident populations and admissions to mental hospitals in the years 1952–9 are as follows:

It will be seen that the increase in resident populations was already slowing up in 1954. In 1955, it changed to a decrease for the first time, and the yearly decrease has since been progressively larger.

The reasons for this change are complex. To some extent, advances in clinical psychiatry seem to be responsible—in particular, the introduction of new ranges of drugs since 1954. The ‘open-door policy’—a term which includes not only the use of unlocked wards, but also new kinds of therapeutic activity, and the development of part-time treatment3—was introduced concurrently. The Mental Health Act introduced informal admission and discharge for the first time, but some hospital authorities had anticipated this by admitting patients informally to ‘de-designated’ wards. There is a major change in policy—the belief that patients should in most cases only enter hospital during the acute phase or phases of their illness, and that several short periods of hospitalization are preferable to one long one. This has led to the open-door policy being nicknamed ‘the revolving door policy’, since one patient may enter hospital half a dozen times in the course of a year.

Alternative methods of care are developing, though it is doubtful whether they yet have an appreciable effect on inpatient statistics. Psychiatric units attached to general hospitals are one form of alternative. In the Manchester Region, a policy of providing peripheral units of this type for the city population has been officially adopted, and other regions have initiated similar though less ambitious schemes. There is a growth in community care. Local authority Mental Health Departments were set up in 1948 with theoretically almost unlimited powers under section 28 of the National Health Service Act. The Mental Health Act 1959 defined some of these powers, particularly with regard to the provision of residential services, such as hostels and ‘half-way houses’, and local authorities were then required to submit schemes to the Minister of Health.

There are thus many factors at work simultaneously, and the situation has well been named one of ‘therapeutic flux’. As a result, a number of forecasts have been made of the immediate decline and ultimate abolition of the mental hospital. The Minister of Health stated in March 1961 that he expected the acute populations of mental hospitals to drop by half in the next 15 years, and the long-stay populations ultimately to dwindle to zero.4 Dr. Alan Norton, in a survey of patients admitted to a mental hospital over the last 30 years, has suggested that ‘the decrease in the number of schizophrenic illnesses becoming chronic may well lead to a fall in the total population of 30 per cent over the next 20 years. If, in addition, changes in national policy are effected, mental hospitals may perhaps be reduced to a quarter of their present size.’5 Dr. A. A. Baker writes, ‘Some people think that, with modern therapeutic advances, rehabilitation, and improved social services, a time will come when there are no long-stay patients,’ and concludes, after an examination of patient statistics in his own hospital, ‘If our present policies continue, and the community provides help in resettlement, I think that the hospital will continue to empty.’6

It will be seen that these forecasts involve three rather different types of argument: the clinical argument that illnesses formerly insusceptible to treatment are now being treated successfully, so that the prevalence of mental illness is being reduced; the statistical argument that, whatever the causes, a decline in the need for beds is in fact taking place, and is likely to continue; and the social argument that patients ought to be treated outside the mental hospital, and that we shall find ways of doing this successfully within the next few years. None of these arguments stands alone. Each is introduced to support the others.

Dr. G. C. Tooth of the Ministry of Health and Miss E. M. Brooke of the General Register Office, in a consideration of their statistical work in this field, comment: ‘It seems unlikely that trends of this magnitude based on national figures are no more than temporary phenomena; though many factors may modify the rate of change, the direction seems to be well established’; but they also point out that there are ‘trends which may have the reverse effect’.7 We now proceed to put the case for the mental hospital, and to discuss some of these trends.

1. The actual decline in resident populations is smaller than it appears to be. We have reproduced in Table 1 statistics which show a decline between 1954 and 1959 of over 16,000 beds. During this period, 9,312 beds were de-designated,8 and these are not included in the later figures, though they were still in use. The real decline was thus not 16,000 but about 7,000—less than half.

Table 1

Admissions and Resident Populations of Mental Hospitals in England and Wales, 1952–9*

* From Annual Reports of the Ministry of Healthy H.M.S.O. No figure for admissions was published in the Report for 1958.

2. The existing beds are not yet even adequate to the need. Despite this decline, there is still an excess of patients over authorized bed-space, amounting at 31st December 1959 to 7·6 per cent statutory overcrowding. The excess of patients over adequate and satisfactory accommodation is very much greater.

3. The decline is unlikely to continue indefinitely of its own momentum. There is no valid reason for assuming that numbers will continue to go down until they reach zero. After an up-curve which has continued for 112 years, it seems rash to project a similar down-curve on the basis of five or six years’ evidence.

Recent improvements in clinical treatment are limited in their effects. The use of thymoleptics and other associated drugs has been valuable in the treatment of depression, but though the acute phase of an illness can now be treated more rapidly, this does not necessarily mean that it will not recur at a later date. The introduction of the phenothiazine derivatives has enabled some patients suffering from schizophrenia to remain in the community for a few years longer, but these drugs do not cure the disease entity known as schizophrenia. They may also be used to mitigate the symptoms of the senile psychoses, but again they do not affect the underlying pathological processes.

Short-stay patients often return for further periods of treatment in hospital—we give some figures later which indicate that, in the three hospitals surveyed, the relapse rate after one admission is about 30 per cent in the first two years.9 Reduction in the numbers of long-stay patients over the past few years has been comparatively easy, because there were some stabilized patients who were quite capable of living in the community, given a little help; but unless a cure for schizophrenia is discovered (and this could alter the whole situation) numbers really may well level off as we come to the hard core of patients who need hospital care.10

With the increase in longevity, we can expect the number of psychogeriatric patients to go up considerably, and this may balance the decrease in other directions.

4. The growth in the community services is not likely to be adequate in the next few years to deal with a major reduction in the mental hospital population. What are the facts about the community services as they operate today? Out-patient clinics have increased in numbers since 1948, but many offer only a minimal service, and appear to be mainly devices for keeping in touch with patients between breakdowns. Since psychiatrists often have to travel long distances to attend clinics, indefinite expansion is not possible without a considerable increase in the numbers of psychiatrists, and might well be uneconomic.

Local authority Mental Health Departments are, as the Younghusband Report has shown, seriously understaffed.11 Few have a psychiatric social worker, and many of the staff employed are untrained, or at best partly trained. Though the proposals of the Younghusband Committee include a doubling of existing staff, this will involve competition with other avenues of work open to people of similar calibre, such as teaching and nursing, where recruitment problems are also severe. Many local authorities already have posts on their existing establishment which they are unable to fill. The creation of more unfilled posts, or the appointment of untrained people who undergo a merely nominal in-training, is not the answer.

This is difficult and exacting work. Not every social worker—or indeed every P.S.W.—is suited to it. The new training scheme for social workers suggested by the Younghusband Committee will, it is hoped, affect the situation favourably in time; but it would be unrealistic to expect these two-year trained workers to do the sustained case-work necessary without proper supervision, 01 to expect them to be forthcoming in adequate numbers unless standards are drastically dropped. As far as psychiatric social workers are concerned, Professor R. M. Titmuss has pointed out that, at the present rate of increase in numbers, it will take rather more than half a century for them to reach the Younghusband recommendations for local authority employment.12

How far are the new and extended proposals put up by the local authorities likely to be translated into fact? The answer to this question depends partly on the supply of workers, but partly also on financial policy. Since the introduction of the block grant in 1959, there has been no specific provision for the Mental Health Services of local authorities, and we have no guarantee that all local authorities will consider this a priority. There are so many entirely reasonable excuses which may be offered for failure to implement proposals—lack of money, inability to obtain building sites, lack of staff—that development may well be slow and will certainly be uneven.

Day hospitals have received a good deal of publicity, but the movement is smaller than is generally supposed. To date, there are only 50 or 60 in operation, and some of these are very small. The total number of patients attending is not much in excess of 1,500, and many of these patients attend for only one or two days a week.13

Although a day hospital is cheaper to build than a full mental hospital, since it requires no dormitory accommodation, the saving on capital costs may be offset by increased maintenance costs. Transport costs are negligible in centres of dense population, but can be high in rural or suburban areas. Some social workers consider that day hospitals require a higher social work staffing than in-patient hospitals, since the patient has constantly to adapt to two different environments, and the home situation needs careful consideration. Since in most cases the local authority provides both transport and social workers, these are concealed costs in that they do not appear in the day hospital’s accounts; but they must be taken into consideration, and we cannot expect the day hospital movement to extend indefinitely outside populous areas.

Day attendances are suitable for patients with a good home environment, enabling them to keep in touch with their normal background rather than entering hospital and then having to go through a process of rehabilitation. They are not suitable for patients with difficult home environments and unsympathetic relatives, and it may be that the daily adaptation to two environments lengthens the course of treatment in some cases.

It is difficult to comment on hostels, since very few are yet in operation; but one can foresee the usual difficulties in finding sites (Tenants’ Associations often raise objections to having such neighbours, on the grounds that their presence ‘lowers the neighbourhood’, upsets the children, and reduces the value of their property). Money and staff may also be hard to find. It is important that hostels should be pleasant, well-equipped places, and not workhouses under another name; that they should take only patients who really do not require the full facilities of a mental hospital; and that those for long-stay patients should accommodate well-matched and sociable groups, not a miscellaneous assortme...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Tables

- Preface

- Introduction

- PART ONE: THE MENTAL HOSPITAL TODAY

- PART TWO: THREE HOSPITALS

- PART THREE: MEASURES OF EFFICIENCY

- PART FOUR: THE MENTAL HOSPITAL AND THE FUTURE

- Appendix1

- Appendix2

- Index