- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Psychology of C G Jung

About this book

This is Volume III of twelve in the Analytical Psychology Series. Originally published in 1942 the present work has grown out of a lecture given before a group of psychologists, physicians, and educators and this is the fifth edition giving a presentation of the elements of Jung's psychology that is intended to give a concise picture, complete in itself, of the central content of the whole system, and above all to facilitate access to Jung's own extraordinarily voluminous works.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Psychology of C G Jung by Jolande Jacobi,Jacobi, Jolande in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

History & Theory in PsychologyThe Psychology of Jung

THE psychology of G. G. Jung is divisible into a theoretical part, whose principal headings can be described quite generally as (1) Nature and Structure of the Psyche, (2) Laws of the Psychic Processes and Forces, and (3) a practical part based on these theories, their application, that is, as a therapeutic method in the narrower sense.

If one would reach a correct understanding of Jung’s system, one must first of all accept Jung’s standpoint and recognize with him the full reality of the psychic. This standpoint is, remarkable as it may sound, relatively new. For up to a few decades ago the psyche was not viewed as independent and subject to its own laws, but was studied and interpreted through derivation from religion and philosophy or from natural science, so that its true nature could not be rightly discerned. To Jung the psychic is no less real than the physical. Though it be not immediately touchable and visible, it is still fully and unambiguously experienceable. It is a world in itself—subject to law, structured, and possessed of its special means of expression. All that we know of the world comes to us, as does all our knowledge of our own being, through the medium of the psychic. For, ‘The psyche is no exception to the general rule that the universe can be established only in as far as our psychic organism permits.’1 It follows then that ‘modern empiric psychology belongs as far as its object and its method are concerned to the natural sciences, but as far as its method of explanation is concerned to the humanities.’2 ‘Our psychology studies both man in a state of nature and man in a state of culture; therefore it must keep both the biological and the spiritual viewpoint in mind throughout its explanations. As a medical psychology it cannot do otherwise than take man as a whole into consideration,’3 says Jung. It ‘investigates the grounds of the pathogenic disturbances of adjustment and follows the complicated paths of neurotic thought and feeling in order to find the way leading back from confusion into life. Our psychology is thus practical science. We do research not for the sake of research, but because of our immediate aim of helping. We could just as well say that science was a by-product of our psychology, not its main goal, which constitutes a great difference between it and what is understood by “academic science”.’4

Jung makes this his premise, but not—as a pure psychologism would do—with the intention of minimizing other ways to knowledge; neither does he postulate, as psychism does, that all reality, nor as panpsychism does, that all being is of a purely psychic nature. To investigate this ‘psychic’ as the ‘organ’ with which we are endowed for comprehending the existing universe, to observe its phenomena, to describe them, and to bring them into a meaningful system is his aim and goal. The theological, psychological, historical, physical, and biological standpoints as well as many others are all equally starting points for the investigation of the facts of being; they are interchangeable, even transposable up to a certain point, and they can be utilized at will according to the investigator’s problem and special interests. Jung takes the psychological, leaving the others to persons competent in their fields, drawing however upon his wide acquaintance with psychic reality, so that his theoretical structure is no abstract system created by the speculative intellect but an erection upon the solid ground of experience and resting only upon that. Its two main pillars are:

- The Principle of Psychic Totality.

- The Principle of Psychic Dynamics.

In the further elaboration of these two principles, as in the practical application of the system, the definitions and explanations given by Jung himself and here identified as such will be employed wherever possible. At the same time it should be mentioned here that Jung generally employs the term ‘analytical psychology’ for the designation of his teachings when speaking of the practical procedure of psychological analysis. He chose this designation after his separation from Freud in 1913 in order to obviate confusion with the ‘psychoanalysis’ of the Freudian school. Later he coined the concept of‘Complex Psychology’, which he always uses when matters of basic principle and theory are to the fore. He wanted to emphasize with this conception that his teachings, in contrast to other psychological theories (e.g., the mere psychology of consciousness or Freudian psychoanalysis with its reduction of everything. to elementary drives), are concerned with complex, i.e., extremely complicated questions. The designation ‘Complex Psychology’ has gained ever more ground in the last years; it is mainly employed in German to-day.

1 Jung, C. G.: Psychology and Religion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1938. p. 49.

2 Jung, C. G.: Psychologie und Erziehung. Zürich: Rascher, 1946. p. 48.

3 Psychologie und Erziehung, p.41.

4 Ibid., p. 53.

[I]

The Nature and Structure of the Psyche

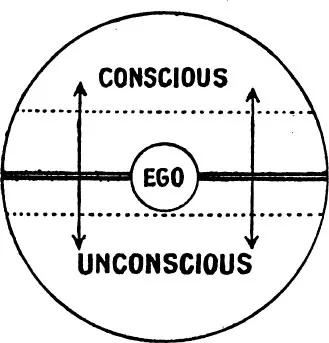

BY psyche Jung understands not merely what we usually mean by the word ‘soul’ (Seele) or ‘mind’ but ‘the totality of all psychological processes, both conscious as well as unconscious’1—that is, something broader than and including the soul, which for him constitutes only a certain ‘limited complex of functions.’2 The psyche consists of two spheres supplementing one another but opposed in their properties—of CONSCIOUSNESS and the so-called UNCONSCIOUS.3 Our ego has a share in both.

The following Diagram I4 shows the ego standing between the two spheres, which not only supplement but also complement or compensate each other. That is, the dividing line that marks them off from each other in our ego can be displaced in both directions, as is suggested by the arrows and the dotted lines in the figure. It is naturally only an expedient of thought and an abstraction that the ego stands exactly in the middle. From the fact that this boundary can be shifted it follows that the smaller the upper part, the narrower is consciousness, and conversely.

Diagram I

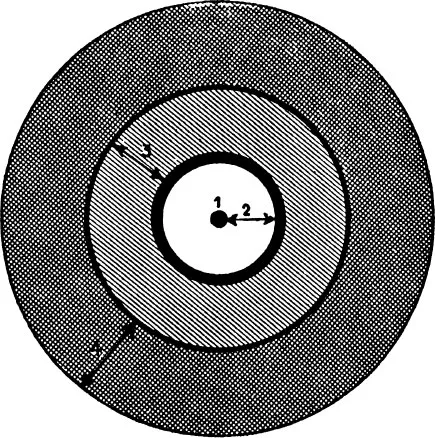

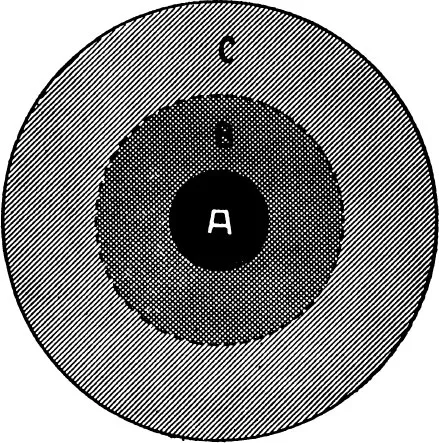

When one considers the relation of these two spheres to each other one sees that our consciousness constitutes only a very small part of the whole psyche. It floats as a little island on the boundless sea of the unconscious. Diagram II indicates the little black point in the centre as our ego, which, surrounded by and resting on consciousness, represents the side of the psyche which is concerned, especially in our Western culture, with adjustment to external reality. ‘Under the ego I understand a complex of representations which constitutes the centrum of my field of consciousness and appears to possess a very high degree of continuity and identity,’5 says Jung, and calls the ego also ‘the subject of consciousness’. Consciousness he defines as ‘the function or activity which maintains the relation of psychic contents with the ego’.6 ‘Relations to the ego, in so far as they are not sensed as such by the ego, are unconscious.’7, 8 The next circle shows how the sphere of consciousness is surrounded by contents lying in the unconscious. Here are those contents which have been put aside—for our consciousness can take in only a very few contents at once— but which can be raised again at any time into consciousness; furthermore, those which we repress because they are disagreeable for various reasons—i.e., ‘forgotten, repressed, subliminally perceived, thought, and felt matter of every kind.’9 This region Jung calls the ‘PERSONAL UNCONSCIOUS’ in order to distinguish it from that of the ‘COLLECTIVE UNCONSCIOUS’, as is indicated in Diagram III.10 For the collective part of the unconscious no longer includes contents that are specific for our individual ego and result from personal acquisitions, but such as result ‘from the inherited possibility of psychical functioning in general, namely from the inherited brain structure’.11,12 This inheritance is common to all humanity, perhaps even to all the animal world, and forms the basis of every individual psyche. ‘The unconscious is older than consciousness. It is the “primal datum”, out of which consciousness ever afresh arises.’13 Thus consciousness is ‘merely built upon the fundamental psychic activity, which consists in the functioning of the unconscious’.14 The notion that man’s psychic life is in the main conscious is false, for ‘we spend the greater part of our life in the. unconscious: we sleep or day-dream.… It is incontestable that in every important situation in life our consciousness is dependent upon the unconscious.’15 Children begin life in an unconscious state and grow into a conscious one.

Diagram II

- Ego.

- The sphere of consciousness.

- The sphere of the personal unconscious.

- The sphere of the collective unconscious.

Diagram III

- That part of the collective unconscious that can never be raised into consciousness.

- The sphere of the collective unconscious.

- The sphere of the personal unconscious.

The unconscious consists of contents that are entirely undifferentiated, representing the precipitate of humanity’s typical forms of reaction since the earliest beginnings— apart from historical, ethnological, racial, or other differentiation—in situations of general human character, e.g., such situations as those of fear, danger, struggle against superior force, the relations of the sexes, of children to parents, to the father- and mother-imago, of reaction to hate and love, to birth and death, to the power of the bright and dark principle, etc.

A basic capacity of the unconscious is that of acting compensatively and of setting up in contrast to consciousness—which normally always gives an individual reaction, adapted to outward reality, to the situation in question—a typical reaction derived from general human experience and conforming to internal laws, thereby making possible an adequate adjustment based on the totality of the psyche.

* * * * *

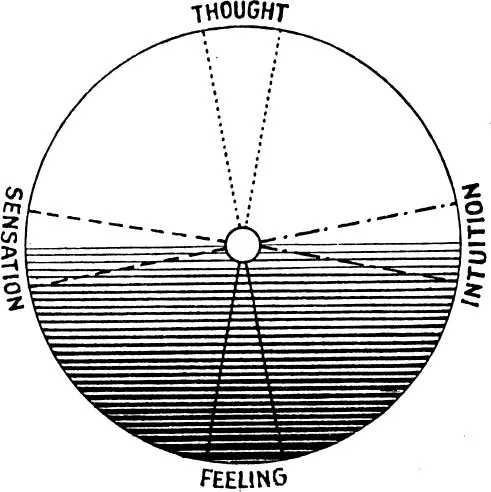

Before we proceed to a further discussion of the unconscious we shall, however, consider the psychology and structure of consciousness more closely. Let Diagram IV16 serve as an illustration. The circle symbolizes again the totality17 of the psyche; at the four points of the compass stand the four basic functions that are constitutionally present in every individual: thinking, feeling, intuition, and sensation.18

By a psychological function Jung understands a ‘certain form of psychic activity that remains theoretically the same under varying circumstances and is completely independent of its momentary contents.’19 The decisive fact is, accordingly, not what one thinks, but that one employs one’s intellectual function and not, for instance, one’s intuition in receiving and working up contents presented from without or within.20 Thinking is that function which seeks to reach an understanding of the world and an adjustment to it by means of an act of thought, of cognition—i.e., of conceptual relations and logical deductions. In contrast thereto the feeling function apprehends the world on the basis of an evaluation by means of the concepts, ‘pleasant or unpleasant, adience or avoidance’. Both functions are characterized as rational because they work with values: thinking evaluates by means of cognitions from the viewpoint ‘true—false’, feeling by means of emotions from the viewpoint ‘agreeable—disagreeable’. These two fundamental forms of reactions are mutually exclusive as practical determinants of behaviour; the one or the other predominates.

Diagram IV

The other two functions, sensation and intuition, Jung calls the irrational functions, since they circumvent the ratio and work not with judgements but with mere perceptions, without evaluation or interpretation. Sensation perceives things as they are and not otherwise. It is the sense of reality par excellence, what the French call the ‘fonction du réel’. Intuition ‘perceives’ likewise, but less through the conscious apparatus of the senses than through its capacity for an unconscious ‘inner perception’ of the potentialities in things. The sensation type, for example, will take not...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Preface

- Preface

- The Psychology of Jung

- [I] The Nature and Structure of the Psyche

- [II] Laws of the Psychic Processes and Operations

- [III] The Practical Application of Jung's Theory

- Biographical Sketch of C. G. Jung

- Bibliography of Writings by C. G. Jung

- Index