- 372 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Psychosurgical Problems

About this book

First published in 1999. This book contains the thirteenth volume in the nineteen-volume series: Abnormal and Clinical Psychology - part of The International Library of Psychology. This study has moved into an examination of the influence of social environmental factors upon the postoperative course of psychosurgical patients. An appendix is included giving the status of the patients included in the first project, two years after their operation. Additional, still later, material on these cases is included in the first chapter, which brings our information up-to-date at the time of going to press.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

NATURE OF THE PROJECT

Fred A. Mettler and Marcus A. Curry Department of Neurology, Columbia University and The New Jersey State Hospital at Greystone Park

The development of methods designed to deal with problems involving more than 3 or 4 variables and less than an infinite number is new. The first Columbia-Greystone project was an attack upon a research situation involving such an intermediate number of variables and the technique employed in its prosecution was that of simultaneous observation by means of collaborative study. While the work was in progress, an interesting article by Warren Weaver (’48) appeared. This classifies scientific problems into: (1) problems of simplicity, in which the number of variables rarely exceeds 4 and is preferably kept to 2; (2) problems of disorganized complexity, in which the number of variables approaches infinity; and (3) problems of organized complexity, in which “a sizable number of factors are interrelated into an organic whole.” Weaver goes on to point out that as early as the seventeenth century, science had learned to deal with problems of simplicity, largely by utilizing mensuration in the physical sciences, and, in the twentieth century, invaded the field of disorganized complexity by applying new statistical and mathematical techniques to physical problems. Of problems of organized complexity he said (’48, see p. 540), “These problems–and a wide range of similar problems in the biological, medical, psychological, economic, and political sciences–are just too complicated to yield to the old nineteenth-century techniques which were so dramatically successful on two-, three-, or four-variable problems of simplicity. These new problems, moreover, cannot be handled with the statistical techniques so effective in describing average behavior in problems of disorganized complexity.

“These new problems, and the future of the world depends on many of them, require science to make a third great advance, an advance that must be even greater than the nineteenth-century conquest of problems of simplicity or the twentieth-century victory over problems of disorganized complexity. Science must, over the next 50 years, learn to deal with these problems of organized complexity.”

On the preceding page Weaver pointed out that problems of organized complexity involve “dealing simultaneously with a sizable number of factors which are interrelated into an organic whole.” So it seemed to us also. As we previously pointed out (Columbia Greystone Associates, ’49) the precursor of our method of approach to a complex medical problem was the technique of cooperative research so profitably employed during the Second World War. It is interesting that Weaver has also selected this, which he calls “the ‘mixed-team’ approach of operations analysis” as one of the 2 modern techniques of dealing with problems of organized complexity. (The other technique he selects is essentially the use of remote derivative machines–which attempt to use on the kind of problems with which we have been concerned have thus far been relatively unprofitable, in our laboratories at least.) Weaver speculated about the effect of such techniques upon individual research (a subject with which we dealt in our first monograph) and might well have questioned whether, under circumstances less compelling than a war, scientists would choose to work together–a question which was raised by Waldemar Kaempffert in reviewing Andrus et al. (’48). That the mixed-team approach of operations analysis is possible in peace as well as war was demonstrated by the first Columbia-Greystone project (Columbia Greystone Associates, ’49). That the method does not disorganize the area in which it was employed and that it can profitably be repeated in the same area is proved by the present communication which constitutes the group report of the second Columbia-Greystone project.

NATURE OF PRESENT PROBLEMS

GENERAL RESULTS OF THE FIRST PROJECT. As a result of the first Columbia-Greystone project (Columbia Greystone Associates, ’49), several observations were made.

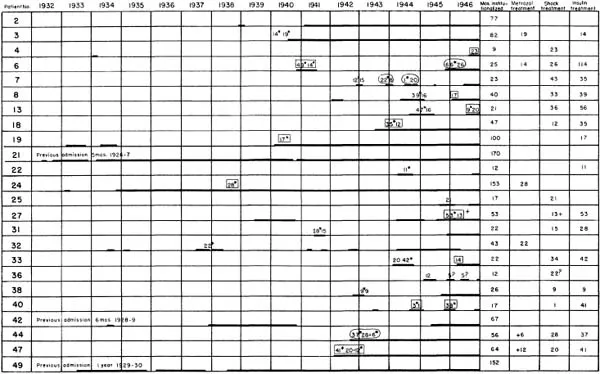

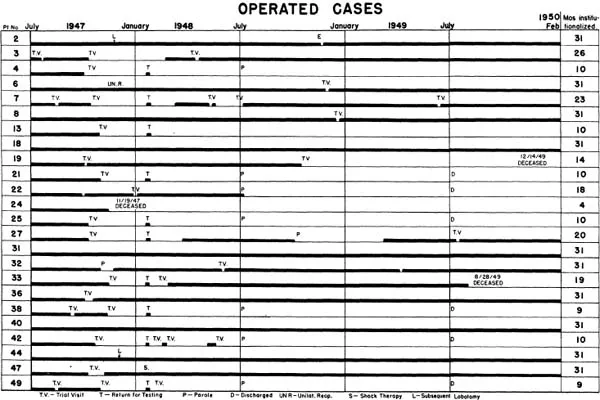

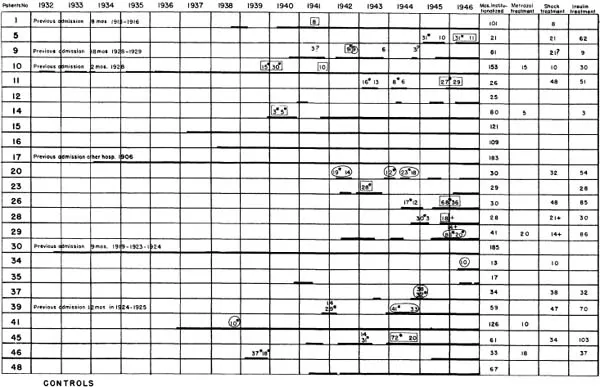

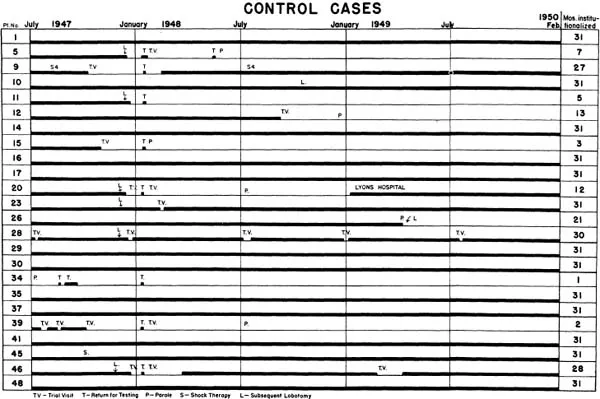

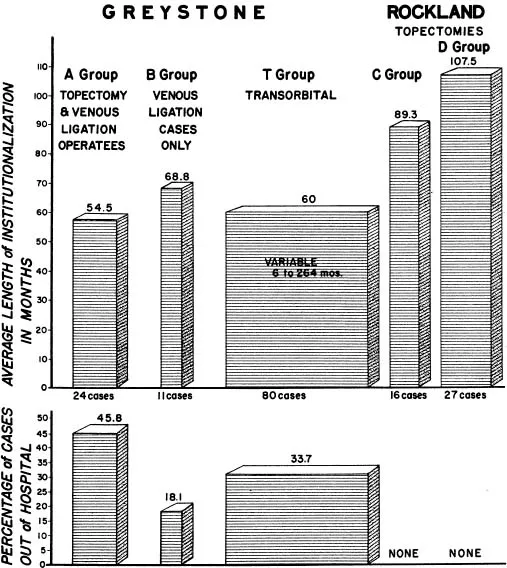

1. In the first place it was found that it was quite unnecessary to disconnect the major portion of the frontal lobes in the supposedly “incurable” psychotic patients studied in the first project in order to secure as high a percentage of returns to society as can be obtained with lateral transcranial (“prefrontal”) lobotomy. Reference to figures 1 and 2, which have been brought up to February 15, 1950, shows the pre- and postoperative record of institutionalization of the 48 individuals who comprised that study. At the present date, November 10, 1950, 3 1/2 years later, of the 48 individuals (24 operated and 24 controls) studied, 4 (cases 12, 15, 34, 39) have been returned to society and are still out of the institution without having passed through any surgical procedure. Of 23 operated cases surviving 6 months after operation, it was possible to release 16 (cases 2, 3, 4, 7, 13, 19, 21, 22, 25, 27, 32, 33, 38, 42, 47, 49, no place could ever be found to take one other who was adjudged ready for parole) at one time or another. Of this number, 4 (cases 4, 13, 21, and 38) did not find it necessary to return to the institution up to the present date (11/10/50), about 3 1/2 years later. Of the 12 who subsequently had to be readmitted, 7 (cases 2, 7, 19, 22, 25, 27 and 49) came back temporarily but are now back in the community, one case (19) dying of pneumonia contracted while out of the hospital. It should be clearly understood in considering the above that only release is considered, no adequate other objective measure of improvement being thus far available. It is to be further emphasized that release is not necessarily synonymous with any of the interpretative or impressional estimates of “improvement” commonly encountered.

2. In the second place it was found that, in the patients in this series, topectomy need not produce any easily detectable permanent degradation in any sphere of function in order to effect a return to society. Moreover, if any undesirable changes from the prepsychotic personality of returned individuals were observed by their relatives, such changes have not been reported to us.

3. In 2 cases in which topectomy had failed to produce any notable changes and lateral transcranial lobotomy was subsequently performed, no improvement was encountered. Results at variance with this have been obtained elsewhere and it is not implied that lobotomy will never “improve” a topectomy failure. The point made here is that if topectomy is a failure the opportunity for “improvement” with lobotomy must also be regarded as somewhat reduced though not as a consequence of the topectomy.

4. Finally, the mortality rate of topectomy was zero and the incidence of the establishment of a convulsive pattern no greater than that reported up to that time after lobotomy. From these observations it might be logically concluded that if psychosurgery is necessary, topectomy is probably preferable to lateral transcranial lobotomy with the possible exception of such cases where functional degradation is deliberately sought.

Other than the above, the results of the first Columbia-Greystone project were of such a nature as to simplify many common speculations about frontal lobe function.

Let us now consider critically the implications of the above findings, bearing in mind that of the individuals allowed out of the hospital throughout the study, 5 were unoperated (one of these returned), that in one who recovered following operation only the superior cerebral veins were ligated and no cerebral tissue was removed (the reason for this procedure, hereinafter referred to as venous ligation, is given on page 23 of Columbia Greystone Associates, ’49). Twenty-three cases received topectomies (or gyrectomies, 3 cases), 8 received lateral transcranial (“prefrontal”) lobotomies, 2 of which were done after topectomy, and 2 received transorbital lobotomies.

IS THE OPERATION DIRECTLY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE RECOVERY?

THE PROBLEM OF DISCHARGE WITHOUT SURGERY. In order to evaluate any therapeutic procedure we must obtain a clear understanding of what factors may operate to produce “improvement,” or the appearance of it, which “improvement” is entirely unrelated to that aspect of therapy upon which the observer’s attention is fixed. It is well known that the rate of “improvement,” even among patients who are ill enough to be committed to mental institutions, is not inconsiderable during the first year of institutionalization. Our operated patients had histories of having been institutionalized prior to 2 years before operation and beyond this length of time the rate of discharge is relatively low (about 10 per cent, which is principally made up from diagnostic categories other than schizophrenia which was the condition nearly all our patients were considered to have). Nevertheless, it has been possible to discharge 4 patients (one of these had been institutionalized for a briefer period than 2 years) without surgery, 3 of whom have now been out for nearly 3 1/2 years. There appear to be several reasons why such a discharge is possible in cases who have been institutionalized long enough to be considered “hopeless.”

FIG. 1. Pre- and postoperative record of institutionalization of the 24 operated individuals in the first Columbia-Greystone project. (Top) Preoperative, (bottom) postoperative record (as of 2/15/50). Notice that several of the cases, notably numbers 2 and 44, were reoperated at a later date. Simple arabic numbers in preoperative period of institutionalization–electro–shock treatments. Arabic number with asterisk–insulin; arabic number followed by black circle–metrazol. Numbers not in box or circle–treatment was effectual. Encircled numbers–treatments exerted less than the desired effect. Boxed numbers–treatment was ineffectual. ?–additional unrecorded treatment believed given. +–exact number of additional treatments given unknown. The death of case 24 is discussed in Columbia Greystone Associates (’49). Case 33 died 8/28/49 of cavitating pneumonic disease which may have been either of acid-fast or non-specific etiology. The onset of the condition was about 3 weeks earlier. No autopsy was obtained. (Preoperative record from, “Selective Partial Ablation of the Frontal Cortex,” by The Columbia Greystone Associates, Fred A. Mettler, Editor, New York, Paul B. Hoeber, Inc., 1949.)

FIG. 2. Pre- and postoperative record of institutionalization of the 24 “control” individuals in the first Columbia-Greystone project. (Top) Preoperative record of the control group, (bottom) “postoperative” record. For superscript symbols see legend of Fig. 1. Numbers not in box or circle–treatment was effectual. Encircled numbers–treatments exerted less than the desired effect. Boxed numbers–treatment was ineffectual. ?–additional unrecorded treatment believed given. +–exact number of additional treatments given unknown. It is to be observed that several of these patients (cases 5, 11, 20, 23, 26, 28, and 46) were operated 5 or more months after the operations shown in Figure 1. (Preoperative record from, “Selective Partial Ablation of the Frontal Cortex,” by The Columbia Greystone Associates, Fred A. Mettler, Editor, New York, Paul B. Hoeber, Inc., 1949.)

FIG. 3. Record of institutionalization and number of cases returned to the community (to 2/15/50) from 5 groups of cases. A and B Schizophrenics, chiefly hebephrenic, C “Involutional” or paranoid schizophrenics, D Schizophrenics, chiefly hebephrenic, T Variable, chiefly schizophrenics.

1. Previous Change. As just pointed out, some individuals improve spontaneously (even as long as 10 years after admission, Boltz, ’48), and, in large hospitals it is possible that this improvement may be missed unless there is an energetic and periodic restudy of all cases in the hospital.

2. Alteration in the Environment. The presence of an individual in an institution is not a measure of absolute inability of such an individual to live outside. It may merely indicate that the individual was unable to cope with the particular environmental situation from which he was committed. Alteration in that environmental situation may render it feasible for the individual to function effectively anew.

3. Alteration in the Patient. It is possible that there may be a few individuals whose morale can be raised sufficiently by a procedure such as “total push” to the point at which they can make enough of a readjustment to resume their places in society, but it is clear that at least some of the past credit which has been given to “total push” should be accorded the 2 factors just mentioned.

Some less obvious ways in which the above-mentioned principles operate in actual practice are worth mentioning. With the exception of one group, in all of our recent projects the patients who have been selected have been pretty generally considered to have had very remote chances for “spontaneous” recovery and to be very refractory to therapy. Nevertheless, definite differences do exist even among such so-called “incurables.” These differences are to some extent expressible by the use of prognostic ratings but, in practice, the differences are likely to exceed the expectation based upon the prognostic rating. While the present study was in progress the Brain Research Project of the New York State Associates was also in effect. Although there were some differences in the prognostic ratings of the cases in the first and second Columbia-Greystone and New York State Projects (the psychiatric disciplines in the 2 latter projects were identical) the rate of discharge in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contributors

- Editor’s Preface

- Contents

- 1. Nature of the Project

- 2. Hospital Management and Social Evaluation

- 3. Surgical Procedures

- 4. General Medical Condition, Including Hematological and Physiologic Findings

- 5. Neurology

- 6. Olfaction

- 7. Vestibular Function and Autokinesis

- 8. The Design of the Psychologic Investigation

- 9. Psychometric Studies

- 10. Complex Mental Functions: Memory, Learning, Mental Set, and Perceptual Tasks

- 11. Attitude Evaluation

- 12. Time-Sampling Study of Behavior

- 13. Psychophysiology

- 14. Discussion of Psychologic Investigations

- 15. Report of the Psychiatric Discipline

- 16. Conclusions

- 17. The Original Columbia-Greystone Patients Two Years After Operation

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Psychosurgical Problems by Fred A Mettler,Mettler, Fred A in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Atención sanitaria. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.