eBook - ePub

Coral Gardens and Their Magic

The Language and Magic of Gardening [1935]

- 380 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Coral Gardens and Their Magic

The Language and Magic of Gardening [1935]

About this book

The concluding part of Coral Gardens and Their Magic provides a linguistic commentary to the ethnography on agriculture. Malinowski gives a full description of the language of the Trobrianders as an aspect of culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Coral Gardens and Their Magic by Malinowski,Bronislaw Malinowski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART V

CORPUS INSCRIPTIONUM AGRICULTURAE

QUIRIVINIENSIS;

or

THE LANGUAGE OF GARDENS

QUIRIVINIENSIS;

or

THE LANGUAGE OF GARDENS

NOTE

WITH regard to the transliteration of the texts which follow, I had to train my ear while in the field to respond to Melanesian sounds, and make a number of phonetic decisions. On the whole this was not very difficult, and for various reasons I have decided not to go beyond the elementary rules laid down by the Royal Geographical Society and the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain: the vowels I have treated as they are used in Italian, Spanish, or Polish; the consonants are represented as in English.

The only difficulty I found was in the fact that r and l are interchangeable; or perhaps it might be more correct to say that the Melanesians have one sound which is a mixture of r and l, and to us sometimes appears more like an r and sometimes more like a clear l. Again the sound represented by the combined l/r in the North (Kiriwinian dialect) is very often represented by an n in the South (Sinaketan dialect). And this is further confused by the fact that the Sinaketans at times adopt the northern forms and vice versa. I adhered to the rule of writing down the sound as I heard it, and have here retained the most usual spellings found in my notes. An alternative method would have been to represent all the three sounds by the same consonant. But I think my system introduces no difficulties or confusion and it is more instructive since it shows the manifold reactions of a European to Melanesian sounds.

I must confess that, looking back on my linguistic observations, I am by no means certain that my phonetic distinctions go as far as they ought to, and I very often find in my notes two or even three transliterations of the same word. This obtains only with vowels, notably with final vowels, and mostly refers to the distinction between the a and the o sounds. But I should like to say that the natives always understood me perfectly. There are actual differences in native utterances, especially when they speak quickly and slur the vowels; and phonetic pedantry, especially when phonetics has no function in discriminating between meanings, seems to me unprofitable.

The apostrophe: the natives sometimes allow two vowels to merge into a diphthong and sometimes pronounce them independently, though there is no glottal stop between them. I have used the apostrophe to indicate that two vowels ought to be broken up.

The hyphen: this should be disregarded phonetically. It indicates certain grammatical distinctions which are fully discussed in Part IV (Div. III, B and C). The possessive suffix -la, however, is a special case and I have adopted the following convention with regard to it. Where a noun can be used alone or with -la, I shall indicate this by bracket and hyphen; e.g. kaynavari(-la). Where words are never used save in the possessive form I shall employ the hyphen only; e.g. tama-la. Words which are never used without the final -la will not be hyphened, as it is impossible to decide whether the -la is part of the root or a possessive, as, e.g., u'ula. The only criterion which can be used in the case of the parts of a plant to decide whether the final -la, is a suffix is found in certain magical formulae where the plant is addressed in the second person and its parts are used with the final -m; e.g. in Formula 17 we find yagava-m taytu, etc. Where a word changes its form when the possessive suffix is added both forms will be adduced; e.g. kanawine- (or kaniwine-)la.

Punctuation: I have followed the same rules as I would adopt in any language. Full stops mark the end of self-contained sentences; semicolons are used whenever co-ordinate and obviously dependent clauses are linked up into a bigger sentence. A comma indicates a subordinate clause or parenthesis, or the need for a slight pause; a dash or colon, a parenthesis, or a long pause marking a break or preceding an enumeration. Paragraphing follows a change of subject, which was usually marked by a longer pause in the discourse.

Abbreviations: I have made use of the following abbreviations in texts:—

e.d.—Verbal pronominal prefix of exclusive dual, e.g. ka-sisu, ‘we two (that is, I and he, excluding person addressed) sit’.i.d.—Verbal pronominal prefix of inclusive dual, e.g. ta-sisu, ‘we two (that is, you and I) sit’.e.p.—Verbal pronominal prefix, used in combination with the suffix -si, of exclusive plural, e.g. ka-sisu-si, ‘we (excluding person addressed) sit’.i.p.—Verbal pronominal prefix, used in combination with the suffix -si, of inclusive plural, e.g. ta-sisu-si, ‘we (including person addressed) sit’.n.—Noun.v.—Verb. r.b.—Round bulky (thing).m.—Man. l.f.—Leafy flat (thing).f.—Female. w.l.—Wooden long (thing).

These conventional signs are not used with any pedantic consistency. It is sufficient for the ordinary reader to be made aware that such distinctions exist and to give him examples of how they are used. The linguist, on the other hand, will soon learn to identify the function of ka- or ta-. Also he is advised to consult my article on “Classificatory Particles in the Language of Kiriwina” (Bulletin of Oriental Studies, Part IV, 1921), where a full list of these will be found.

DIVISION I

LAND AND GARDENS

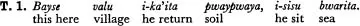

1. The most fundamental terminological distinction to be found here is that referring to ‘soil’, ‘land’ or ‘habitat’, on the one hand, and to ‘sea’, on the other. The natives define the first by the noun pwaypwaya, ‘earth’, ‘ground’, ‘terra firma’, and the other by bwarita, ‘sea’. The term pwaypwaya would be used in this sense at sea to define a distant vague form as being a piece of land and not a reef or cloudbank. In description or information the natives would say:—

This means that ‘at that spot, the land comes back (ends) and there remains the sea’. But this distinction is only distantly connected with gardening, so we...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- ANALYTICAL TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PART FOUR AN ETHNOGRAPHIC THEORY OF LANGUAGE AND SOME PRACTICAL COROLLARIES

- PART FIVE CORPUS INSCRIPTIONUM AGRICULTURAE QUIRIVINIENSIS; or THE LANGUAGE OF GARDENS

- PART SIX AN ETHNOGRAPHIC THEORY OF THE MAGICAL WORD

- PART SEVEN MAGICAL FORMULAE

- Index