![]()

Part I

Industrialisation and the British building industry

![]()

Building is only organisation:

social, technical, economic, psychological

organisation.1

The term ‘industrialisation’ applied to building implies the transition from a primitive or simple era of production to one that is more advanced and usually understood as involving a rational approach to the processes required to produce buildings more effectively and more efficiently, with the expectation that they will also be cheaper.

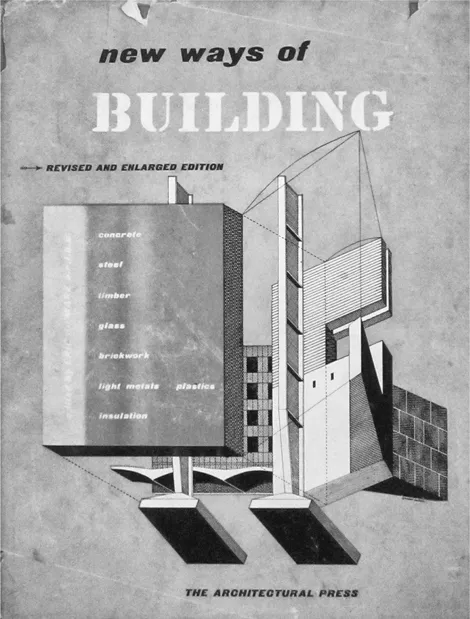

In Britain, the term came into common usage in the 1950s but it was notoriously difficult to define and commentators struggled to include all the relevant factors. Roger Walters, an early proponent of industrialisation in the architectural press, proposed: industrialised manufacture + industrialised assembly = industrialised building.2 This formula included the entire building process from raw material to site assembly and Walters interpreted the term ‘industrialised assembly’ as having two potential meanings. First, the use of machinery on site to increase efficiency but with many of the final operations, for example, the placing of concrete and the laying of bricks, still being done by hand, and second, in a ‘hypothetical future’, the simple assembly of machine-made, fully finished components. Site mechanisation was very low throughout the 1940s and early 1950s despite the promotion of innovations, for example, mechanised wheelbarrows and brick hoists, in the architectural and building press and Ministry of Works’ advisory booklets3 (Figure 1.1). It was the ‘hypothetical future’ of interchangeable components suitable for a wide range of building types that inspired many architects in the post-war period. Walters was typical of many in assuming that modular co-ordination of these components was a prerequisite of industrialised building.

This approach to transforming the process of building was, of course, not new, and examples of rationalisation through the prefabrication of components or parts of buildings can be found throughout the history of construction.4 It is questionable exactly when the introduction of prefabrication into the building process occurred. Some commentators include the pre-cutting and assembly of timber frames in fourteenth-century house building. The building of Georgian London included the prefabrication of sash windows and other timber components (Clarke, 1992; McKellar, 1999) and the mass-production of stone ornamentation in Eleanor Coade's factories (Summerson, 1991). By the end of the eighteenth century, many of the characteristics, both technical and contractual, of a rapidly modernising industry were emerging (Satoh, 1995). Early nineteenth-century prefabrication was typified by the export of timber ‘colonial cottages’ to Australia, South Africa and other outposts of the British Empire (Herbert, 1978). By the 1840s and 1850s, the introduction of cast iron as a building material saw the increasing use of factory-made components, and in England the building of the Crystal Palace in 1851 was paradigmatic of prefabrication at component level. Here, the myriad small cast iron components that made up this extremely complex structure were prefabricated in an industrialised process, that is, they were manufactured under factory conditions by steam-driven machinery, and the rationalisation of the building process extended from the factory to the organisation of their assembly on site (Peters 1996).

Figure 1.1 Cover of New Ways of Building (1948), edited by Eric de Maré, London: Architectural Press

In Britain, the years between 1914 and 1942 were a particularly fertile period for experimentation in prefabrication and standardisation. Patrick Abercrombie, Stanley Adshead and Charles Reilly, all based at the Liverpool University School of Architecture, promoted standardisation of house building in the architectural press (Swenarton 1989: 33–40). The Tudor Walters Report, published in 1918 under the chairmanship of Raymond Unwin, is generally known for its recommendations on space standards and design but it also contains extensive detail on materials and methods of construction. One of its most far-sighted recommendations was that efficiency would be increased through better site organisation, accurate costing and regular employment for building trade workers.5 The following year, the Local Government Board appointed the Committee for Standardisation and New Methods of Construction. This committee investigated and reported on a large number of innovative building components and housing types that were revisited in the 1940s in the Ministry of Works' Post War Building Studies. Research on standardisation was continued in 1924 under the Committee on New Methods of House Construction, set up by the Ministry of Health, which published four reports in 1924–1925 on the relative merits of housing in steel (including the Weir, Atholl, Thorncliffe and Telford houses), timber and concrete and a wide range of pre-cast concrete blocks and slabs. It is notable that the members of this committee included two representatives of organised labour, Richard Coppock (NFBTO) and George Hicks (AUBTW), neither raising objections to the new materials and methods recommended in the reports.6

The ultimate success of factory-based mass-production was achieved in the US automobile industry in the early years of the twentieth century. There were parallel developments in Europe where the relationship between design theory and production process was central to the development of the Modern Movement. The principles of mass-production promoted by Henry Ford, together with F.W. Taylor's theories of scientific management, were well known, but the role of the Deutscher Werkbund was equally influential in the formation of a specifically German rationalisation movement. Schwartz (1996) has documented the cultural discourses on mass culture and the struggle for ideological control between the members of the pre-1914 Werkbund and, by the early 1920s, its resolution so that the mass-produced type became the goal of all design activity.7 The ‘type’ was the key to the architectural interpretation of mass-production.

Typisierung means agreeing on certain forms for doors, windows, hardware, room sizes, installations, plans and finally entire buildings; norms means quantifying these types. [Types and norms] are a self-evident result of machine production.8

The architectural manifestations of this were evident throughout Germany in the 1920s, for example, in the Siedlung built by Gropius in Dessau and the work of Martin Wagner in Berlin. With the exodus of European intellectuals from the Third Reich in the 1930s, America became the home of many Modern Movement architects. Here Gropius continued his experiments in industrialised production of housing with another German emigré, Konrad Wachsmann, but these failed to become commercially successful (Herbert, 1984). Wachsmann, however, continued his investigations into industrialised building and design, set out in great detail in The Turning Point of Building (1961).

Henry Ford's production methods influenced the ideas of the American industrialist and writer, Alfred Farwell Bemis, whose work became known in British architectural circles mainly through the publication of his trilogy The Evolving House.9 Volume III, Rational House Building (1936), became a key text for architects committed to standardisation and prefabrication, and is notable for being the first proposal arguing that industrialisation required a standardised module as the basis for progress. Bemis suggested the size of the module as either 4″, derived from the size of a timber stud, or 3″ as derived from a brick plus mortar and it was this proposal, in particular, that made a resounding impact on British architectural thought on industrialisation.

Less well known, but equally important, was Alfred Bossom's account of skyscraper building published in 1934, where an early manifesto for industrialisation was set out, which, as well as standardisation and prefabrication, argued for efficient site organisation.10 Based on his experience in the USA, Bossom recommended that architect and contractor co-operate from the outset of a contract, with detailed drawings prepared in advance of site work together with ‘Time and Progress Schedules’ and long-term agreements with operatives' organisations and materials suppliers. Regarding building as of necessity a co-operative enterprise that was best entered into as teamwork, he understood that in Britain, with its rigid class structure, this ideal was going to be difficult to achieve: ‘A hundred reasons of social classification and professional pride have made this ideal of co-partnership, this sense of common interest, difficult to attain and to act upon in England.’11

During the Second World War, the relatively recent experience of the difficulties encountered in reconstruction after the First World War led to a number of government committees being set up as early as 1942. Investigations into solutions for the coming renewal of the built environment began with the knowledge that the condition of the construction industry at the end of the war was going to be almost identical to that of 1918. The most important of these committees, in terms of prefabrication and standardisation in building, were the Directorate of Post-War Building and the Directorate of Building Materials, both under the aegis of the Minister of Works. Together, these two bodies undertook a large programme of research into innovative building methods culminating in the publication, between 1944 and 1946, of 33 volumes in the series Post-War Building Studies. Much of the experimental work published in Building Studies was undertaken by the BRS, and as Saint (1987) points out, the Garston Headquarters of BRS between 1943 and 1945 were to serve as a form of informal finishing school for a number of socially and technically minded architects who later held influential posts in the rebuilding of Britain.12

Planning for reconstruction

Towards the end of the Second World War, a plethora of handbooks and guidebooks aimed at educating and informing the British people on the shape of the new post-war urban and rural environment were produced.13 The government's White Paper on Housing, published in 1945, laid out a post-war reconstruction programme of 750,000 dwellings to provide a dwelling ‘for every family desiring one’.14 A further 500,000 new dwellings were needed to complete the slum clearance programme, based on the assumption that housing output would rise to a maximum of 300,000 dwellings by the end of the second year after the war. Meanwhile, the immediate crisis of homelessness in the aftermath of war damage was to be alleviated by the erection of 158,748 temporary houses produced by the Ministry of Works and the Ministry of Supply15 and a massive programme of repairs.

The production of this enormous output of permanent new dwellings, at a time of massive shortages of both skilled labour and materials, was to be brought about through the use of innovative methods of construction. These included various techniques of prefabrication in concrete, timber or steel and alternatives to ‘traditional’ construction, for example, in situ concrete. The standardisation of plans, specifications, components and the production of codes of practice were also proposed as means to increase efficiency. The shortage of skilled building labour was to be solved by increased recruitment to apprenticeship schemes and the retraining of adults on short-term construction courses to boost the construction labour force to the 1.25 million considered necessary to complete the reconstruction plan.16 These changes were anticipated as necessary precursors to the modernisation of an industry perceived by the government as having low productivity or, in the terminology of the late 1940s, functioning well below ‘productive efficiency’.17

The Labour government of 1945–1951 had difficulty in meeting the housing demands of reconstruction, and housing output did not start to rise until the Conservatives came to power. This has been blamed on shortages of skilled labour, materials and the licensing system for new building works but also on a lack of centralised control of the industry so that building workers employed in small firms spent more time on repairs to bomb damage than on new-build (Rosenberg, 1960). However, the repair and refurbishment of houses were a remarkably efficient operation and...