![]()

Part1

Popular Music and the Challenges to National Identity

What is the most popular music genre in Spain that can represent the musical specificity of the country? To answer this question, almost everyone will think of flamenco as the national music of Spain. Flamenco has been, and probably still is, the best-known music from Spain worldwide. This reality is felt as limited and incomplete for many audiences in Spain. First, because the world of flamenco is very deep, crossed by styles, subgenres, local cultures or ethnic issues, it is very difficult to define what exactly flamenco is. Second, because of this idea that flamenco represents Spain, it gives the impression of cultural homogeneity that is far from reality. Third, because for many Spaniards, this representation of a culturally homogeneous country obviously comes from a heritage of decades of cultural nationalism linked to the long dictatorship of Franco.

Thus, we have chosen the issue of the challenges to Spanish national identity to open this book in order to offer the reader the broadest view of a diverse musical landscape. Enric Folch’s Chapter 1 is both a revision of what flamenco has been and is at the moment and a study on how the contact between flamenco and other popular music genres has produced music with new meanings in new contexts. Folch’s chapter offers a journey that begins with the Andalusian gypsies in the rural areas who embody the descriptions of the European travelers in the Romantic period to the young, urban musician who played rumba in the working-class neighborhoods in Madrid and Barcelona. Flamenco is now a diverse world, crossed by the dynamics of traditional music, popular music and world music, offering several options to musicians and to those who simply want to enjoy the music and its symbolic universes.

Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia historically have been the regions of the Spanish state with the strongest claims for political autonomy, based mainly on the vindication of their cultural differences, specifically on language. Cultural issues have been the starting point to define a different regional identity, and music has had a central role in these processes. We offer a case of study from each of the regions in order to reflect on the connections between cultural diversity, political claims and historical consequences.

Jaume Ayats and Maria Salicrú-Maltas in Chapter 2 resume the history and evolution of the nova canςo in Catalonia in the last period of Franco’s dictatorship, from the 1960s to the 1980s. The young cantautores (singer-songwriters) who decided to sing in Catalan even though this language was forbidden were simultaneously working for the modernization of the regional culture and pointing out the repression of the rights of free speech and assembly. While claiming that “we need Catalan songs for today,” they were mixing cultural and political vindications. By the time and the arrival of democracy, these regional political issues had become less centered on the musical discourse of this group of musicians, but younger generations, as we will see later, still identify this music with a dark, boring and isolated period very far removed from their interests and realities.

However, the end of the dictatorship and the arrival of a democratic regime and a much decentralized political organization of the country did not mean the end of political claims by the peripheral regions of the country. During the 1980s, the Basque Country was caught between the violence of the terrorist group ETA and the industrial crisis. In this turbulent context emerged the Basque Radikal Rock, as Karlos Sánchez Ekiza writes in Chapter 3. This scene expressed the controversies about the Basque identities and the related political programs; at the same time, very influenced by punk aesthetics and attitudes, it was a strong criticism of the situation of the youth in the Basque Country who were experiencing terrorist violence, police repression, drug addiction and unemployment. The magic solution to this situation provided by music was to create a utopia; following the punk heritage, Jamaica was the model for the imaginary, new Basque Country, a way to escape reality and to imagine a way out. Radikal Rock was able to evolve by using basic attitudes that range from rage to irony and sarcasm to fuel their songs.

If the Basque youth created an invented link with an impossible country, Galician musicians challenged the discourse of Spanish identity, recreating an imaginary community of Celtic music. Javier Campos Calvo-Sotelo argues in Chapter 4 that the success of Celtic music in Galicia in the last few decades is a result of a cultural policy designed to divert energies from the menace of independence towards a symbolic community. The integration of Galician music into the Celtic brotherhood eroded the specificity of the region and, at the same time, transferred energies to transform a political project into a cultural one that posed no threat to the large European states.

![]()

1

At the Crossroads of Flamenco, New Flamenco and Spanish Pop

The Case of Rumba

Enric Folch

Flamenco and new flamenco are important in Spanish popular music because they give it a national identity clearly different from Anglo-American pop music. The Andalusian cadence (Am-G-F-E), the Phrygian mode, flamenco guitar strummings and picked runs, hand claps, all contribute to the export of the genre since they are easily identifiable by foreign listeners.

This perceived homogeneity contrasts with the inner ideological splits we find in flamenco studies, which usually center on the importance of the Gypsy contribution to this music. Literature on flamenco has attributed to Gypsies and non-Gypsies different repertories (seguiriya and fandango), different rhythms (12-beat cycles and ternary) and even different types of voice (hoarse and clear). But all these elements constitute integral parts of flamenco and both Gypsies and non-Gypsies have practiced and mastered them. Even so, during the evolution of the genre, there has been real confrontation over the Gypsy or non-Gypsy paternity of the genre, whether ethnic elements or traditional roots are emphasized.

This debate ended with the arrival of new flamenco insofar as a new style of Latin American origin, rumba, came into the genre, giving it great popularity. This popularity was so great that later even Spanish pop adopted rumba in its repertoire.

Gypsies and Non-Gypsies

“The Gypsies call Andalusians gachós (non-Gypsies), and in turn are called flamencos by them” (Machado y Álvarez [1881] 1975). So starts the first essay on flamenco, the Foreword to a collection of flamenco lyrics collected by one of the first Spanish anthropologists. It also includes a short biography of the non-Gypsy cantaor, Silverio, a contemporary of Machado y Álvarez.1

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the term “flamenco” was applied very gradually to the musical style, even if at that time flamenco had begun to establish itself as a musical genre in step with the popularization of the art. The dances known as “country dances” and “national dances” came to be called “flamenco dances” when singers started to be sought as much or even more than dancers. All this happened mainly in cafés cantantes,2 where this music was part of a varieté spectacle that could include other kinds of music, non-musical numbers, or even early cinema projections. This sort of establishments were a result of the new industrial cities where workers, often with a peasant past, had fixed-hour working days, earned a salary, and had little free time.

For the first time since their arrival in Spain in the fifteenth century, Gypsies who sang, played or danced this musical genre had the right to perform on a public stage, that of the cafés cantantes where the audience consisted of all social classes. From that moment on, the identity of the Gypsy was no longer reduced to that of the petty thief or the jester; in fact, one of the best strategies for Gypsies to circumvent these stereotypes was to become a professional musician.

Machado y Álvarez distinguished between flamenco and Andalusian songs, associating flamenco with the Gypsies (ibid.); some time later, in 1922, the well-known composer of the Spanish nationalist movement Manuel de Falla distinguished between cante jondo (deep song) and flamenco, associating cante jondo, not flamenco, with the Gypsies (Manuel de Falla 1988);3 finally, Gypsy cantaor Antonio Mairena distinguished between the cante gitano (Gypsy song) and the cante flamenco (flamenco song), polarizing that extreme current of pro-Gypsy thought (Molina and Mairena [1963] 1979). In this Gypsy song we could include styles like seguiriya, soleá, bulería, tientos, tonás, tangos, but also malagueña del Mellizo and fandango del Gloria, because they are Gypsy creations.4 Even so, the image of only Gypsy flamenco was reinforced when it passed from the written word to the screen with Rito y geografía del cante (1971–1973), a weekly program on Spanish television filmed in Andalusia in the fashion of an ethnographic documentary. Its producers intended to launch a pro-Andalusian nationalist message under the cover of the symbolic romanticism of Gypsy imagery (Washabaugh 2005) but only succeeded in creating the idea that for Gypsies to sing and dance flamenco was a natural everyday activity. This presentation of flamenco as a Gypsy-only creation did nothing but reinforce in the public imagination the already prevalent Mairenism.5

For the Gypsy population, the fact of being in the forefront of this program entailed a before and an after. If in the mid-nineteenth century Gypsies had the opportunity to acquire a more socially acceptable identity by becoming flamenco artists, in the television series they appeared to be the authentic “owners” of the genre. However, this appropriation had unexpected consequences. On the one hand, it upheld Gypsy identity but, on the other, the gypsiness of flamenco ceased to be the main preoccupation of young Gypsy musicians, precisely because it was then taken for granted.

Once the generation of Antonio Mairena, full of good musicians who appeared on the series, had managed to demonstrate that theirs was Gypsy music and that it was flamenco or at least the best aspect of flamenco, the next Gypsy generation did not feel obliged to follow the model. However, soon there appeared a young Gypsy cantaor called Camarón de la Isla, the possessor of an extraordinary traditional repertoire that appealed to young and old alike. He was a musician who later would become an international figure.

Camarón gave a new turn of the screw to the whole of flamenco, and in a second stylistic phase would leave behind the old aesthetic principles and venture into new musical territory. This gave wings to the new Gypsy generation. Just as the Gypsies contributed artists and styles to the reconstruction of the genre during the 1954–1974 period until they definitively appropriated it, so many of them will also later deconstruct it through fusions and crossovers with other genres, among them rumba.

How to Overcome Mairenism

In his book, the Gypsy cantaor Antonio Mairena criticized the non-Gypsy cantaor Antonio Chacón for not possessing a hoarse voice, but Mairena also kept away from the whole repertoire derived from the fandangos, claiming they were not of Gypsy origin (Molina and Mairena 1979). Of course, fandangos did not cease to be sung, but nobody remembered Antonio Chacón until the young non-Gypsy cantaor Enrique Morente appeared paying homage to the old master and winning the National Prize for Popular Music in 1978.

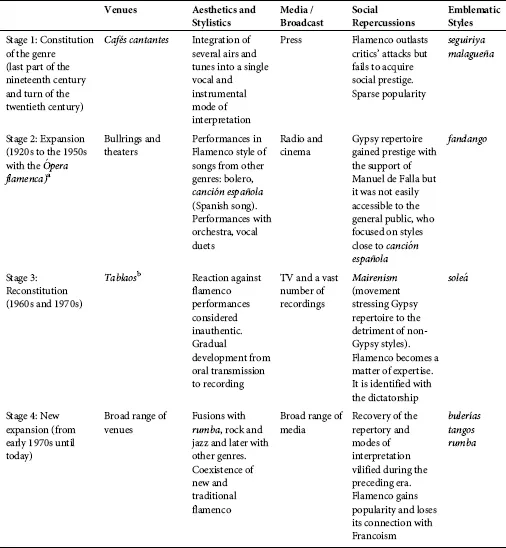

Daringly, the part of flamenco which was disdained by Mairenism but that had succeeded in the period known as Ópera flamenca (see Table 1.1) was revisited by a restless young Enrique Morente, nurtured by old masters such as Pepe el de la Matrona who had heard Antonio Chacón, who in turn had heard Silverio. At this point, flamenco was still transmitted orally.

Table 1.1 Stages of flamenco development

Notes:

aÓpera flamenca has nothing to do with opera but it was thus named because under that name it was taxed at a very low rate. During this period, impresarios organized flamenco troupes that toured theaters and bullrings throughout Spain.

bTablao is a place that offers exclusively flamenco music. The tablaos cater for a foreign or non-participative audience who also go to enjoy haute cuisine dining. They started around 1954.

The young Enrique Morente built up his repertoire from three different types of sources: flamenco singers who also sang Spanish song, such as the non-Gypsy Pepe Marchena (a heresy for Antonio Mairena); canta...