eBook - ePub

Innovation and Economic Crisis

Lessons and Prospects from the Economic Downturn

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Innovation and Economic Crisis

Lessons and Prospects from the Economic Downturn

About this book

The recent financial and economic crisis has spurred a lot of interest among scholars and public audience. Strangely enough, the impact of the crisis on innovation has been largely underestimated. This books can be regarded as a complementary reading for those interested in the effect of the crisis with a particular focus on Europe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Innovation and Economic Crisis by Daniele Archibugi,Andrea Filippetti in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Knowledge Capital. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Setting the Scene

1 At the Root of the Crisis

Some Proposed Explanations

The way in which money and finance affect the behaviour of the system can be perceived only within a theory that allows money and finance to affect what happens.

(Minsky, 1986, p. 4)

The ‘Minsky Moment’

In September 2008, for the first time since 1866 in the United Kingdom, several people were neatly queuing in front of the entrance of a bank – Northern Rock – to claim their money back, as they were frightened that the bank could go bankrupt. This episode followed quite a hectic summer in which the sub-prime mortgage market in the US had shown the first signals of tension. This was the side effect of a slowing down in the real estate market after an impressive boom in the 2002–2007 period.

Very soon the tension spread to the entire financial market, and eventually the interbank market was almost stuck. Simply put, banks had lost confidence (the basic engine of finance) in one anothers’ solvency. Bear Stearns was the first giant investment bank to go bankrupt, followed by the largest provider of mortgages in the US, Countywide Financial. After the bankruptcy of one of the most prestigious American investment banks, Lehman Brothers, in September 2008, it became very clear that what was happening was an extraordinary crisis across the entire financial market.

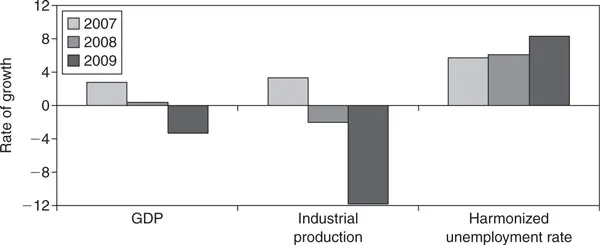

It took just a few months for the crisis to spread from Wall Street to Main Street, with huge effects on the real side of the economy. In OECD countries (Figure 1.1), the change in gross domestic product (GDP) shows a modest 0.31 per cent rise in 2008 and a fall equal to −3.41 per cent in 2009; similarly, industrial production plunged by −11.46 per cent in 2009 while unemployment rose considerably, with a 43 per cent increase in the harmonised unemployment rate in the three-year period from 2007 to 2009.

Figure 1.1 Real gross domestic product, industrial production, unemployment rates, total OECD countries (source: authors’ elaboration on OECD.stat database).

Every great crisis has its hero: these days are, by all accounts, the ‘Minsky moment’ (Cassidy, 2008)1 (see Figure 1.2, which appeared on The New Yorker in February 2008). Hyman Philip Minsky (1919–1996) was above all a Keynesian economist who believed that the neoclassical school was the reduction of the Keynesian revolution to banality (Minsky, 1975). His scientific programme, as illustrated in his major text Stabilizing an Unstable Economy (Minsky, 1986), was basically to replace the equilibrium theory with an economic theory based on a business cycle associated with a financial instability view of how economy operates.

Figure 1.2 The Minsky moment (source: The New Yorker, February 2008).

By emphasizing the Keynes key lessons of the General Theory, Minsky insisted upon the intrinsic instability of the capitalistic system due to the growing prominence played by the financial side of the economy. Investment, he claimed, is basically a financial decision. With the upswing of the business cycle, investment tends to grow along with the financial assets that support it. For reasons that he explains (Minsky, 1986), he concludes that the liability structures that support investments tend to deteriorate over time. This natural tendency of the economic system to move from robust to fragile finance is at the heart of the financial instability hypothesis advanced by Minsky.

According to many observers and scholars, this is exactly what has happened again in 2008–09. The financial market had deteriorated so far that it was no longer sustainable. The slowdown of the real-estate market and the following tension in the mortgage sector were only the incidental cause that led to the burst of the bubble; deeper causes should be looked for in the way the financial system had grown and transformed over the past decade along an unsustainable path. This, then, was the Minsky moment. But since economists are overwhelmingly apt to seek causes, soon the question became: what caused the crisis in the financial sector? This chapter reviews three main explanations that have been proposed.

Three Possible Explanations of the Causes of the Crisis

We have already made it clear that the main concern of this volume is not that of analysing the causes of this crisis. However, in this section we discuss three main explanations that could be at the root of one of the deepest depressions since that of 1929: (1) the financial explanation; (2) the global economic imbalances explanation; and (3) the technological explanation.

The Financial Explanation and the ‘Credit Crunch’

According to several scholars, the current crisis originated with the creation of a financial bubble that was the result of an excessive accumulation of debt (see, among many others, Brunnermeier, 2009; Crotty, 2009; Roubini and Mihm, 2010). This was associated with a dramatic surge in the supply of credit made possible by both regulatory arrangements and an expansive monetary policy, primarily driven by the Federal Reserve. Innovation in the financial sector also made a substantial contribution, as it allowed the detachment of credit from risk,2 as well as increasing the leveraging (the ratio between assets and liabilities) of the banking system. This had led to a dramatic increase in the supply of credit. Between 1981 and 2008, the debt of financial institutes in the US grew from 22 per cent to 117 per cent of the gross domestic product (Roubini and Mihm, 2010). Minsky himself had already stressed the increasing role played by financial innovation aimed to create new money during periods of expansion. A similar argument regarding the importance of financial innovation in the 1929 Great Depression was made by Galbraith (1954), who stated that ‘the most notable piece of speculative architecture of the late twenties […] was the investment trust’ (p. 72), which by 1929 had marketed a third of all new capital issued in that year.

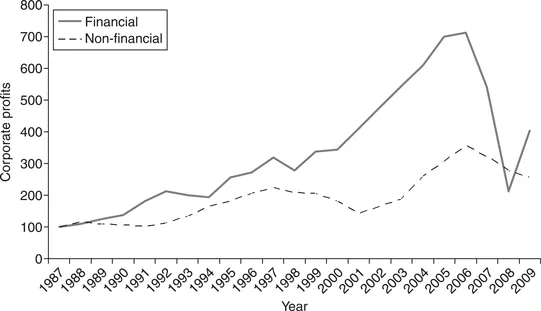

In a thought-provoking book, Johnson and Kwak (2010) make their case against the ‘ideology of finance’ that pervaded the American political and economic system in the last decades. They claim that the dramatic financialization of the economy was the result of an impressive increase in power of the large banks in the US. Some figures reported in their book are worth reiterating. In 1978, the financial sector borrowed thirteen dollars in the credit markets for every 100 dollars borrowed in the real economy; by 2007, this had grown to fifty-one dollars. In support of the ‘too big too fail’ argument, they show that from 1995 to 2009 the value of the six larger banks in the US grew from less than 20 per cent to around 60 per cent of US GDP. A brief look at Figure 1.3, reporting the corporate profits in the US in the financial and non-financial sectors over the past two decades, gives an indication of the dramatic expansion of the financial sector compared to that of the non-financial sector.

Figure 1.3 Corporate profits, financial and non-financial corporations, 1987–2009 (base year = 1987), US (source: authors’ elaboration on Bureau of Economic Analysis National Income and Product Account).

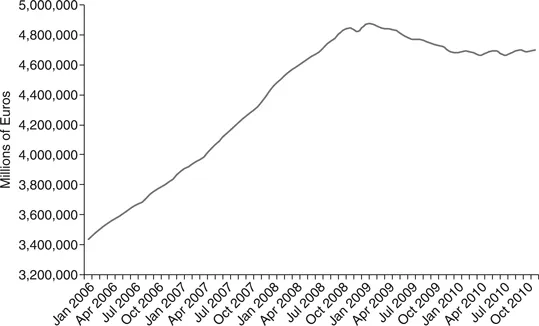

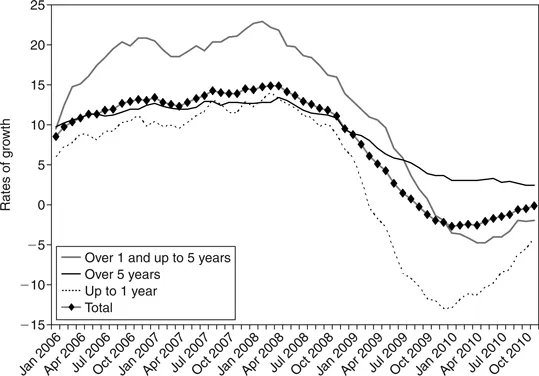

Those who advocate that the crisis originated in the financial system argue that it spread to the real sector of the economy as a result of a credit crunch. The credit crunch reflects a situation in which the financial and banking system reduces the availability of credit for internal reasons that do not directly depend upon demand conditions and monetary policy. Figure 1.4 shows the total value of loans to non-financial corporations, for the period 2006–2010, aggregated for the Eurozone. Across the Eurozone, a generalized reduction in loans has occurred in the business sector, equal to a −3.8 per cent drop from the peak of January 2009. Figure 1.5 displays the rate of growth of loans to non-financial companies for different periods of maturity. It reveals that short-term loans have been the most affected, followed by mid-term loans, while the rates of growth of long-term loans have been positive following a substantial plunge. In order to support the financial nature of the current crisis, the key question is whether these trends are the causes or the results of the depression.

Figure 1.4 Loans to non-financial corporations: outstanding amounts at the end of each period (stocks), Eurozone, 2006–2010 (millions of euros) (source: European Central Bank).

Figure 1.5 Loans to non-financial corporations for different periods of maturity (annual rates of growth), Eurozone (source: European Central Bank).

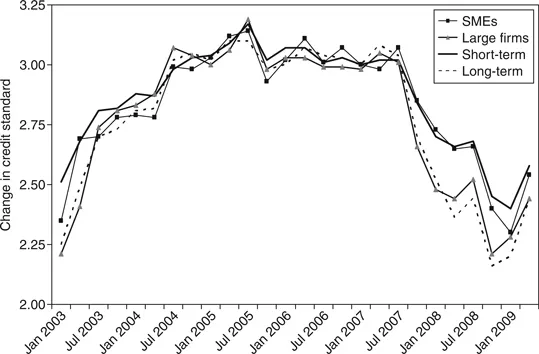

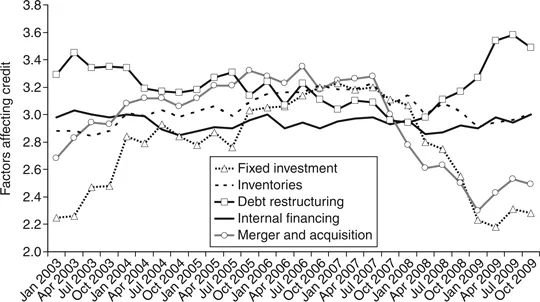

One way to seek to corroborate this hypothesis is to look at qualitative data on the relationship between the banking system and the business sector concerning the conditions of credit. In this regard, a relevant source is the Survey on the Access to Finance of SMEs in the Euro Area, carried out by the European Central Bank (ECB) every six months in the Eurozone.3 Figure 1.6 shows the average response to the following question put to the bank: ‘Over the past three months, how have your bank’s credit standards as applied to the approval of loans or credit lines to enterprises changed?’ Responses ranged from 1 (tightened considerably) to 5 (eased considerably). It is easy to see that a remarkable tightening occurred, starting in the summer of 2007, with a recovery beginning at the start 2009. This was particularly the case regarding long-term credit and large firms. Figure 1.7 shows the response to the following question: ‘Over the past three months, how have the following factors affected the demand for loans or credit lines to enterprises?’ Responses ranged from 1 (low) to 5 (high). Starting in the autumn of 2007, there was a sharp plunge in the role played by fixed investment and merger and acquisition activity. At the same time, the demand for loans has been increasingly affected by the need of restructuring the debt.

Figure 1.6 Response to the question: ‘Over the past three months, how have your bank’s credit standards changed as applied to the approval of loans or credit lines to enterprises?’ (source: Survey on the Access to Finance of SMEs in the Euro Area, European Central Bank, 2010).

Figure 1.7 Response to the question: ‘Over the past three months, how have the following factors affected the demand for loans or credit lines to enterprises?’ (source: Survey on the Access to Finance of SMEs in the Euro Area, European Central Bank, 2010).

These results can be coupled with those arising from a survey on credit conditions carried out in fourteen European and emerging markets countries by Markit (2009). The survey, performed in January 2009, covered 2,875 small and medium manufacturing firms. One of the most interesting results was that firms reported that their net demand for credit had increased (apart from the case of Poland).

Overall, the reduction of credit and tightening of the credit standard by the banking system, along with high demand for credit and an extremely loose monetary policy, seems to lend some support to the credit crunch hypothesis.

Global Economic Imbalances

The financial explanation put forward above is sometimes referred to as the ‘easy credit and lax regulation’ argument. Some scholars argue that the dramatic expansion of credit and debt is only the manifestation of more profound imbalances. They contend that the savings glut in Asia led to a major part of these savings flowing into the US, with the result that there was too much money in the US financial system chasing too few opportunities, leading to a ‘Global Savings Glut’ (Dooley et al., 2005).

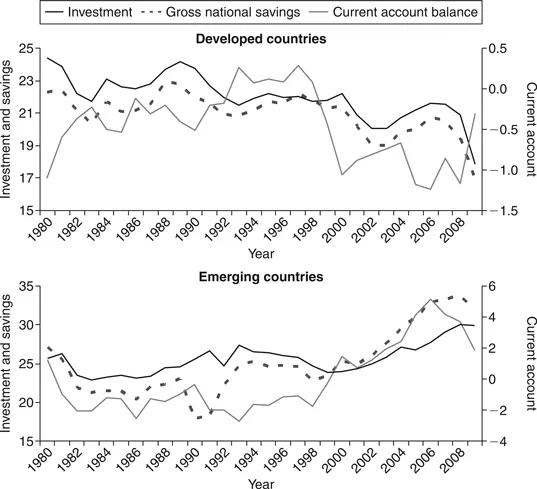

The route of the global imbalances can be tracked in Figure 1.8, which highlights the mirroring dynamic in investment, savings and current accounts in developed and emerging countries. The dramatic growth of the emerging economies and oil exporters (thanks to the surge of the price of natural resources) led to an excess of savings and a large surplus in the current accounts of these countries. On the other hand, developed countries experienced larger increases in the current account deficit (Faruqee et al., 2009).

Figure 1.8 Investment, gross national savings and current account balance (rates of growth), 1980–2008: developed and emerging countries (source: authors’ elaboration on IMF, World Economic Outlook database).

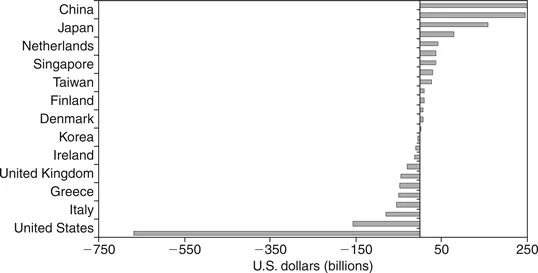

To balance this deficit in the current account, massive capital inflows took place, initially into US government debt, and later into the more attractive financial products. Almost the entire increase in current account balances from emerging economies has been matched by the increase in current account deficit in a single country, the US (see Figure 1.9). Thus, for the first time in centuries, the direction of capital flow is not from West to East, but from East to West. As Ferguson (2008) put it, ‘China has become the banker to the US’.

Figure 1.9 Current account in billions of US dollars, 2008 (selected countries) (source: authors’ elaboration on IMF World Economic Outlook database).

Further, a not insignificant role in this financial flow from emerging to developed countries has been that played by sovereign wealth funds, which are state-owned investment funds comprising financial assets such as stocks, bonds, property, precious metals or other financial instruments. The amount of these financial assets has risen spectacularly over the past decade as a result of the increase in the price of natural resources, primarily oil and gas (The Economist, 2008).

Advanced countries have managed to sustain high levels of consumption and house market prices thanks to capital inflows, financial innovation and an expansion of credit. The presence of these large amounts of savings – or the Asian ‘savings glut’ – has been argued to be the reason for the dramatic increase in the US mortgage market, in which 100 per cent mortgages could be obtained by people with no income, no job and no assets (Ferguson, 2008). This generated the bubble in the housing and financial markets, which eventually burst. According to this line of argument, the solution lies in a process of reduction of global imbalances. In this regard, scholars have called for global financial reform and global governance reform, in which international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank should play an increasing role (Adam and Vines, 2009; Crotty, 2009; Wade, 2009).

Along similar lines of reasoning, another interesting explanation for the origin of global imbalances is that put forward by Jagannathan and colleagues (2009). They maintain that these imbalances have their root in a labour supply shock that occurred in developing countries, particularly China. They explain that the urban population in China increased by nearly 300 million from 1990 to 2007. A major part of those who migrated to urban areas have become part of the Western world’s workforce through working for industries that export to the West. The effect on the developed world’s labour supply is of similar magnitude to that of the Western world’s increased access to land and natural resources following the discovery of the Americas. The sudden increase in labour supply from workers in developing countries because of globalization should have resulted in significant sections of the population in developed countries experiencing a decline in their living standards as more and more manufacturing and service jobs were outsourced.

This process was mitigated by the flow of cheap liquidity from abroad during this period, which brought about the housing bubble and created the illusion of wealth among households sustaining high levels of consumption. This had the effect of masking the real structural changes that were taking place in the world economy. According to these authors, the financial crisis is thus just the symptom, while the main cause was the labour s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I: Setting the scene

- Part II: The uneven impact of the crisis across countries: some explanation

- Part III: The innovative behaviour of the firm in times of crisis

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Reference

- Index