![]()

A preliminary explanation of the paracommons

This book views natural resources and the commons from the point of view of losses, wastes and wastages. The book argues that in a scarce world, competition for losses, wastes and wastages increases. These previously dismissed, unwanted and unavailable (by definition) resources are increasingly scrutinised and sought out. Because losses, wastes and wastages are expressed by resource efficiency, the book explores efficiency and productivity. Thus the book views efficiency gains as a common pool resource expressed in the question ‘who gets the material gain of an efficiency gain’? (See Box 1.) The ‘who gets the gain’ in the first part of the question refers to a material gain as a physical resource, while the ‘efficiency gain’ in the second part of the question is a performance improvement in the efficiency of a natural resource system. For example, when the physical efficiency of an irrigation system goes from 54 per cent to 59 per cent (this is the performance gain), it means that the irrigation system is now consuming five units more (it ‘got’ the material gain). However, those five units could have gone to someone or something else. The paracommons is about the competition for the five units ‘freed up’ by the efficiency improvement. This seemingly innocuous example hides many paradoxes requiring mental agility in the first place and considerable analysis in the second place.

Therefore the paracommons can be seen as a commons of the material gains from efficiency improvements, or put another way; the competition for the inefficient part of resource use. To distinguish competition for wastes and wastages, the prefix ‘para’ has been added to ‘the commons’. Furthermore, the paracommons places efficiency-centred endeavours ‘in limbo’ problematically located on the boundaries between current efficiency, future intended efficiency, the design of interventions to raise efficiency and final productive, depletive and distributional outcomes. The book explains this framework and contrasts the paracommons with the commons using examples from irrigation and river basins, and carbon, forests and ecosystem services. It is proposed that the paracommons modifies the principle of subtractability (that resources subtracted in one place are not available elsewhere) requiring new thinking on property rights. The Jevons Paradox, when raised energy efficiencies paradoxically fail to reduce aggregate consumption, is one expression of the paracommons.

Box 1 Freeing up saved resources for other users – three examples

In recent years, the Australian Government has introduced ‘water-saving infrastructure projects’ for irrigators to ‘save’ water and deliver water to the river system, mainly through on-farm irrigation efficiency projects. Gains from savings are shared between the irrigators and the river/environment.1

Similarly in the United States, reviews of prior appropriation legislation has meant that efficiency gains associated with irrigators and their water rights can now be debated as in this text from the start of Norris (2011) paper ‘the United States Supreme Court's recent decision in Montana v. Wyoming brings to the forefront one of the most complicated and contested facets of irrigation efficiency: who owns the rights to the conserved water?’2 (In this Yellowstone River case, downstream Montana filed a complaint against Wyoming because the latter's irrigators used up the conserved water created by a technology switch from flood irrigation to sprinkler which reduced drainage water that previously reached Montana.)

Staying in North America – at the transboundary scale, Mexico and the United States examine the Colorado Compact to share water savings made from the lining of irrigation canals and upgrading of irrigation methods in Mexican irrigated agriculture. This agreement is known as Minute 319.3,4

Many questions apply. What are the starting conditions? Are selected technologies appropriate? Will these gains really go to those intended and what influences these outcomes?

1.1 The paracommons – step by step

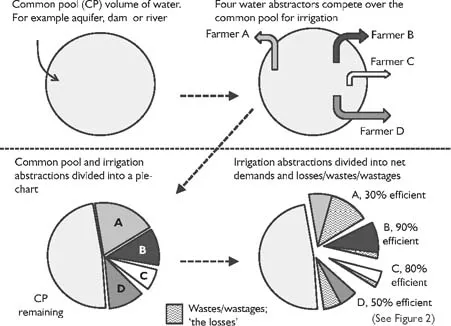

Using the example of irrigation, Figures 1 to 3 introduce how the paracommons arises and how it relates to the commons.5 All three figures provide a connected sequence and should be read together. Figure 1 begins with a common pool in the upper left-hand corner. In this example it is a body of freshwater in a dam, aquifer or stream. Moving to the next part of Figure 1 (upper right), we see four irrigators or farmers competing over this common pool of water, facing competition and rivalry. In the bottom left of Figure 1, the farmers' water demands are shown as four segments (A, B, C, D) of a water allocation pie, leaving some remaining in the common pool. Moving to the bottom right of Figure 1, part of these irrigation abstractions have efficiency losses. These losses arise, for example, via evaporation of water from bare soil instead of via useful crop transpiration. The four farmers each have four different efficiency levels and thus varying sizes of the ‘waste/wastage’ fraction of their pie segments.

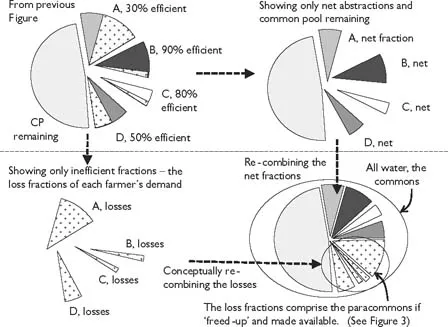

Moving to Figure 2, the first part in the upper left imports the final bottom-right ‘pie’ from Figure 1 to continue the story. The net demands (the beneficial

Figure 1 From the commons to abstraction and inefficient fractions

crop transpiration part) and the inefficient fractions are teased out into two separate diagrams – upper right and lower left of Figure 2 respectively. Finally, by collating the wastes and wastages together as one combined segment, we can show in the bottom right of Figure 2, how ‘the paracommons’ begins to arise, showing that it sits alongside the commons (or within depending on how you view it).

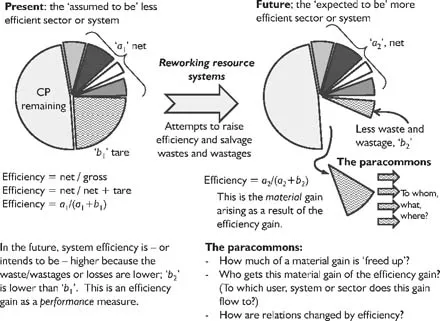

However, to fully understand the paracommons is to recognise that current ‘losses’ (or assumptions of losses) frame a wish for a future more efficient system, and that if this higher efficiency is achieved, then these losses are potentially but not inevitably ‘freed up’ and available to competition. Figure 3 introduces the final crucial part of how a future ‘resource efficiency gain’ might deliver a reduction in losses and a consequent material gain. In other words, a ‘new’ resource (termed here a ‘paragain’) has potentially been ‘found’ by reducing losses. It is this material paragain that sets up the question ‘Who gets the gain of an efficiency gain?’ However, so far, everything appears quite linear and predictable; that an efficiency gain can be achieved, and that this frees up a material new resource which is then competed over.

On the contrary, this relationship between efficiency gain, material gain and ‘new resource’ is not linear, easily achievable and predictable. The translation of a change in efficiency ratio into a new resource is highly complex and mediated by many factors. It is for this reason that I use the term ‘resource efficiency

Figure 2 Contrasting the paracommons with the commons

Figure 3 Arriving at a ‘paragain’ by efficiency improvements

complexity’ and argue that new salvaged resources are ‘pending’ (hence the terms the liminal paracommons and paragains) and behave paradoxically subject to various factors. As explained in the next chapter, and in Figure 11, the story continues with what happens and doesn't happen to this ‘new’ resource.

1.2 A brief explanation of the word ‘paracommons’

Adding the prefix ‘para’ to the word ‘commons’ gives the word ‘paracommons’. ‘Para’ signals ‘alteration and contrariness’ (as in paradox) associated with the unpredictability of the paracommons where the control of losses is problematic and the destination of gains from efficiency gains cannot be anticipated. ‘Para’ also has a meaning of ‘being alongside’. The paracommons puts competition for an efficiency gain alongside competition for resources in their natural capital state. ‘Para’ denotes another type of ‘alongside’ (like the word ‘parallel’) arguing that neighbouring users are physically connected by efficiency and the ensuing destinations for salvaged losses.

Box 2 Etymology of the prefx ‘para’

Para: Etymology: <ancient Greek παρα ‘by the side of, beside’, hence ‘alongside of, by, past, beyond’, etc., cognate with fore adv. and prep. Also παρά has the same senses as the preposition, along with such cognate adverbial ones as ‘to one side, aside, amiss, faulty, irregular, disordered, improper, wrong’; it also expresses subsidiary relation, alteration, comparison, etc. Forming miscellaneous terms in the sense of ‘analogous or parallel to, but separate from or going beyond, what is denoted by the root word’ (OED, 2012).

1.3 The paracommons and the discarded apple core

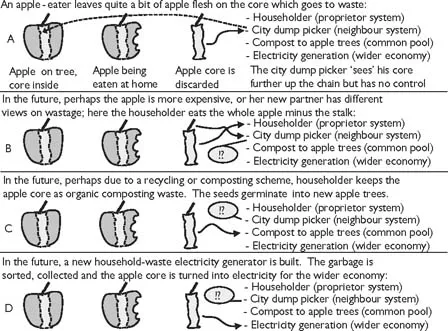

Figure 4 reveals aspects of the paracommons by looking at the fate of an apple and its ‘to-be-discarded’ apple core which ordinarily goes to the city garbage where it might be picked over by people whose lives depended on households throwing away food and goods. For both the apple on a kitchen table and the apple core in the city dump there are two commons. The household members compete over the apple and the city dump ‘harvesters’ compete over who eats the apple core. However these two commons are separate from each other. What turns this situation into the paracommons are other options that might or might not transpire depending on shifts in efficiency and the core's destination. The household deciding to eat more food (case B in Figure 4) or recycle the apple in garden compost (case C) deprives the waste pickers at the garbage dump of their sustenance. The waste picker fears the outcomes of a household drive to be more efficient and ‘green’. Alternatively, a waste furnace (case D) needing waste to generate electricity deprives the householder, the waste picker and the compost of ‘their’ core.6 Aspects of the paracommons are:

Figure 4 Who gets the apple core if and when less or more is wasted?

• Competition over the apple core takes place between four types of groups; householder, garbage picker, furnace operator and those who speak on behalf of apple tree populations.

• In the paracommons, these four parties are termed ‘destinations’. In the same order they are: the proprietor, the neighbour, the wider economy and the common pool (or environment).

• The destination of the core depends on switches and changes in interests and technology affecting the sequencing and cascading of the apple core through the household then onto the city dump, furnace or compost.

• These four destinations cannot easily communicate with each other over who gets the core as do rivalrous commons harvesters inside the house and at the city dump.

• The common pool nature of the core in the paracommons is related to perceptions about today's waste alongside ‘savings’ to be made in the future. There are spatial and temporal transitions involved.

1.4 The paracommons, households and hospital wards

Introducing the paracommons, some parallels with efficiency gains in two other systems (car fuel budgets...