![]()

Chapter 1

The Enigma of Serial Killers

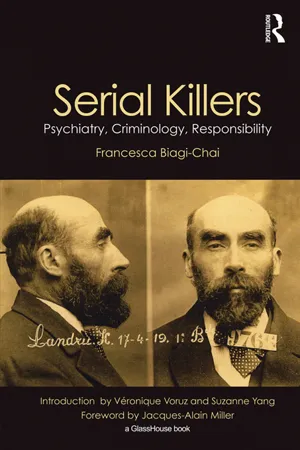

Brought to light in 1919 in the immediate aftermath of the war, the Landru case was one of the most resounding criminal cases of the twentieth century. For the first time in history, public opinion was confronted with an unprecedented form of murder. A married man, a father of four, who was in love with a singer whose lover he had been (and who was thus apparently normal in every respect), was to become the killer we still know today who over a four-year period killed 10 women and one young man. Of course, before him, at the end of the nineteenth century, Joseph Vacher, a criminal nicknamed ‘the Ripper of the South-East’, had committed numerous crimes in a state of delusional vagrancy. But he was successively found to be mad, to have recovered, to be not guilty by reason of insanity and finally to be guilty. What is more, his case gave rise to disputes between experts on the question of madness. This was not so with Landru. With his incredible duplicity and his apparent normality, the latter was to introduce the modern enigma of serial killers into French legal history.

Through the numerous studies that, to this day, have been dedicated to Landru, posterity only remembers this killer of women as a greedy and wilful murderer. The question of madness has never been the subject of research. Yet, this was the question that was on everyone’s lips and in all newspapers from the day of his arrest until his execution. As all serious authors have come to agree, the case file reveals a certain number of elements destined to remain, it would seem, forever inexplicable, because they do not seem to fit within any comprehensible logic. Why did Landru, who was an inventor in mechanics before becoming a conman and then a murderer, not succeed in marketing his inventions given that they were perfectly fit to be commercialised, as we shall see? Why did Landru, who was supposed to have killed for money, not choose victims who were a little richer, since this would have provided him with the comfort he never truly obtained? Why didn’t he kill his mistress? These are all questions the psychoanalytic reading we propose can offer answers to; answers that will give logical consistency to the personality of the famous criminal, one that people have refused to see and that is none other than that of his madness.

Through the study of the Landru case, the question of madness and its relation to apparent normality is broached, and we consider whether the concept of crisis or excess is still sufficient to account for what we know today of madness. I argue that madness can go so far as to model itself on utmost conformity, donning the mask of the banal and everyday. It can take the very real form (not the romanticised one) of what is now of the order of myth: Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde. Madness can account for the figures that we speak so much about on occasion, but which we struggle to perceive and conceive of as truly existing. In this radical duplicity, there is something which is, quite literally, incredible. Yet we confront this incredible (which we call ‘real’, a stumbling block, a rupture, a void of sense, a hole in the common signification of things) daily in our practice as psychoanalysts and psychiatrists. The real is what breaks the thread of subjective stories and the linearity of their discourse. It is what makes our practice something other than a simple, well-meaning understanding or even empathic conversation, for it touches on the register of consequences: namely, whether the subject will be able to occupy a dignified place in the world amongst others, or return to failure and passage to the act? Through this book, I would like to transmit (in other words, make the reader feel) something of the real in its constitution as reality for the subject Landru.

The real is not reality; it is a modification of it, a subjective translation. It is an interpretation of the meaning of life, of everything the subject understood through his or her first sensations, through the first words and first looks that accompanied his or her entry into the world: there where the intimate sense of life took hold of him or her and transformed itself into joy or sorrow; there where, in the bond to the parents, something was conveyed of the desiring and loving relation, of the couple and of what it would mean to be a father or mother in his or her turn one day. If the bond to others, the civilising bond, is to be found in the knot of the first identifications, it must be understood that sometimes this knot is not tied. This is what happens in psychosis.

In psychosis, the subject is in the social bond, but he is there in his own way, a way which is sometimes strange, fragile, difficult to understand and kind of foreign. But whatever the place occupied by the psychotic subject in this bond (even if it is the most withdrawn, isolated, free or dangerous one it could be), this subject cannot be dissociated from the bond to others, even when he breaks from it in the passage to the act. The latter cannot be understood and interpreted independently of the subject rooted in his familial, cultural and social context. No subject can be excluded from the community of humanity. My study will show how Landru drew from the time in which he lived and how the crimes he committed bear its mark, albeit in a delusional manner. In addition, the Landru case will pave the way for a reading of further case studies, which I briefly introduce here. I will reread the case of Pierre Rivière, a well-known parricide from the beginning of the nineteenth century, and the case of Donato Bilancia, an Italian serial killer from our postmodern era, who has been referred to as a ‘random killer’ and who is currently incarcerated.

Considering the real in its relation to the subject modifies the notion of responsibility, without for all that cancelling it out. If the characteristic of the real is to impose itself as a constraint on the subject, the subject’s response to this constraint remains somehow inalienable, because it is singular and has an identity beyond structure. It is here, in this response, that the articulation of the subject to the reality of his life and also to the real of his criminal acts is laid bare. Degrees of responsibility are measured according to this articulation. This is what I will develop in my conclusion, devoted to the question of criminal responsibility, since the time seems ripe to open a dialogue between psychiatry, insofar as it is oriented by psychoanalysis, and the criminal justice system.

Crime and Lack of Motive

There are crimes that occur without one being able to connect them to a crisis, to a delusional moment, without any detectable motive. We are then confronted with the strange, with the enigma of meaninglessness. If meaning always presents itself as obvious because of the satisfaction it affords and so instantly secures conviction, non-sense, by contrast, provokes and maintains suspense and dissatisfaction. Nonsense is not the opposite of sense – it necessarily gives rise to a call for elucidation, a desire to know, an expectation. And this expectation endures, unchanged, as long as the elements of an explanation do not impose themselves with an irrefutable logical consistency – in other words, as long as the proposed explanations fail to secure an unreserved assent, an ‘effect of truth’.

This is why we appeal to specialists, so that they can clarify what cannot be grasped. We ask them if the criminal knew what he was doing at the time of his act and to what extent he is liable to repeat the act. All the more so when it is a question of crimes that are supposed to be groundless as the apparent absence of causality opens up troubling perspectives: whatever their place and circumstances, such crimes appear to be reproducible at any time as acts of pure caprice. More than any other crime, the murder said to be ‘without motive’1 is frightening because it carries a strong potential for repetition. With these inexplicable murders, we thought we had reached the height of the enigma of crime. But with serial killers, an even greater enigma emerged, that of repeated murders where lack of motive and non-sense are reproduced each time.

Here, we are confronted with criminals for whom a first crime, a first passage to the act, produces no shock, no retroactive effect. Is this act forgotten? Erased? But how? For these individuals, crime seems to manifest itself like a simple event in the strange psychopathology of everyday life. An ordinary man, a good friend, a father, in no way distinct from his social, domestic and cultural environment, can at the same time be a killer who repeats his murders with the greatest indifference.2 The enigma of serial killers, considered to be a real bane in the United States, occupies a large place in the media and countless films and novels try their hand at producing a psychological explanation for this incomprehensible phenomenon that continues to increase. In Europe, the isolated cases now constitute a series and over the course of a few years, the list has grown considerably. Serial killers make newspaper headlines, supply material for television programmes and for the many studies that endlessly seek to grasp the psyche of the individual who comes to rend the social fabric, to damage the cohesion of countries that think of themselves as rich and call themselves developed. But what is neglected, because it is not recognised, is the real insofar as it is distinct from reality, although it is the active core of the passage to the act.

With serial killers we can no longer imagine a hot-headed act, a crisis, a moment of madness. We have to account for their acts in other ways: either the criminal is a pervert and enjoys his crimes with full conscience and volition (and we have to circumscribe this jouissance, to demonstrate the existence of this perversion and not merely assume it) or the criminal is mad and, in this case, madness shows facets, nuances and a complexity that extends far beyond what is immediately perceptible.

Reconsidering the Landru Case

To this day the case of Henri-Desire Landru remains a mystery. My objective is to disentangle madness from perversion without any ambiguity and to render this madness visible and legible to all without resorting to subterfuges or approximations. My approach is to examine madness through the psychoanalytic concepts elaborated by Sigmund Freud and developed by Jacques Lacan and again more recently by Jacques-Alain Miller in his annual seminar, L’orientation lacanienne.3 People have talked and written much about Landru and because of that everyone thinks they know this modern Bluebeard who burnt women in his stove. Yet, the mystery emanating from this famous case continues to perpetuate the dark aura of serial criminals and authorise all manner of lucubration. It refers to an even greater mystery, the one we used to ascribe to fatality, to the arbitrariness of the will of God or of absolute chance, and that we ascribe today – too easily it must be said – to the immediate satisfaction of impulses, to intolerance to frustration or to ‘predatory’ drives. These pseudo-causalities are merely the avatars of ancient fatum. However, this absence of knowledge tends to be elaborated as a legendary story for a spellbound audience in a way that smacks of obscurantism.

In order to shatter the blindness that the Landru case carries with it, I decided to reopen the voluminous case file to examine every single piece of evidence, every element. In so doing I have consulted the whole of the archive and assiduously compared it against the numerous press and newspaper articles that reported the investigation and the trial at the time. In this work, I have disregarded nothing and have not considered anything to be irrelevant or impossible to integrate into the account that I will give here. On the contrary, and as the practice of the monograph requires, I took account of all the elements, including those that appeared to be the most insignificant, the most bizarre or the most absurd. It allowed me to find and reconstruct, through every detail and every utterance, the guiding thread of Landru’s life and personality.

A Biography Elucidated by Psychoanalysis

The result of my research leads me to suggest the concept of a ‘biography elucidated by psychoanalysis’. Such a biography is not a purely chronological narration, nor is it a ready-made explanation. It is the writing of a monograph that conforms to the structure of the real of the unconscious which it reveals; it is a biography that demonstrates how the real is knotted within the story of someone’s life. It exposes what a subject can be in his development above and beyond appearances: in other words, his presence and even the effects of his rhetoric. ‘A biography elucidated by psychoanalysis’ is inscribed at the juncture of the universal and the particular, insofar as it allows a constant to be discovered in the network formed by the statements and behaviour of a subject. This constant is linked to the primary modality through which the subject entered reality. It is the mark that the signifier leaves upon him, when the speech of the other, diffracted between statement and enunciation, between sayings and ways of saying, is incorporated. The words, strictly speaking, affect him, because they are borne by the love and desire of another before him, of another who addresses him. The subject becomes aware of the other in his first emotions at the same time as he becomes aware of himself. This relation to the other, insofar as he is himself a subject, is founded in the field of speech and language, a field that Lacan calls Other with a capital O. This is why human relations are not pure rivalry, but rivalry mediated by law.

There should be no mistaking what the law is. It is not merely what is written in the civil or criminal code: it is also the symbolic pact that unites people and prohibits incest and parricide. The function of the father, as exception, gives sense to the capacity instituted in man that allows him, through the play of identifications, to think of himself, to imagine himself in the place of the other and which we call the Imaginary. The expression ‘the field of the Other’ means that a discourse is made regarding reality through speech, and that an intimate reality, a real, is created and a jouissance felt. After Freud, Lacan would say that a portion ofjouissance is definitely lost for man through the fact that he speaks. This is why Lacan, later on, will place a bar on the O, which is to say that the Other is also barred. Indeed, jouissance emerges in the same movement as the limitation of jouissance. In other words, there is no such thing as a total jouissance. This explains Lacan’s double aphorism, which could be understood as contradi...